About cities

Philadelphia and Dhaka

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf

I never realized I had to check my emotions watching an architectural documentary. I silently chastised the film-maker, Nathaniel Kahn, for making me a bit beside myself when I should have been sharp as a razor as an architectural critic watching a documentary on the architect Louis Kahn, who not so incidentally happens to be Nathaniel's father. In a predictable but interesting way, Nathaniel and I have become friends over the skyline of a city that we both share in some indescribable manner (I am talking about Dhaka). So he asked me to introduce his already award-winning film "My Architect: A Son's Journey" at the 29th Hawaii International Film Festival in Honolulu since he could not be there. The film screened at noon, and for some unknown reason I was anxious since the morning. It is still an inexplicable thing for me requiring a sympathetic understanding, this life of a passionate architect that intersected two faraway cities, Philadelphia and Dhaka. I said my conventional part in introducing the film, how Louis Kahn was next to Frank Lloyd Wright the greatest American architect, who at the most sterile moment of modern architecture brought back themes of history, myth, and memory, and the banished notions of marvel and wonder into architecture all over again, and inspired generations of architects into considering architecture as a kind of spiritual mission. I knew a few things about Louis Kahn, his incredible passion, his masterful presence in Dhaka, I came to know most of his colleagues and members of his family, I studied in the shadow of his space, I wrote about his work… but even then I was not prepared for the deeply moving quality of the film. Nathaniel's film is clearly genre-bending as it interweaves three poignant themes in a beautifully crafted cinematic work. Louis Kahn died tragically in 1974 in the restroom of New York's train station after returning from India, and his body lay unclaimed for three days in a New York city morgue. The passport on his body did not have an address. Kahn had crossed it out. Why did he do it? Was he trying to imply something? It's truly a mysterious ending of a life given to acknowledged work of timeless and monumental character. The film begins from there, from that haunting death. The other two themes are more interwoven: the work of the architect and the people around him. The film is not truly about architecture, although architecture becomes a protagonist in a story, a moving story of a son's quest to find out who his celebrated father was. The film is about Kahn as an architect and the complexity of a life that included three families, of which only one was "official" in the conventional sense. Since his father died when he was only eleven, for Nathaniel the film was a journey and a catharsis, a journey to find out who his father really was, and a catharsis in order to come to terms with a man who led an extraordinary, and in some sense, unconventional social life, and was not present for him as a regular father would be. How best to know such a man, such a father? Since Kahn was supremely an artist, Nathaniel thought best to travel to see his creative work and meet the people involved around them. As Anne Tyng, one of the women whom Kahn was intimate with, says to Nathaniel, pointing to one of Kahn's buildings, "He lives in his buildings, in these spaces." The evening of the screening, I sent an e-mail to Nathaniel: "After the film, when I was mobbed by a group of people thinking that I was part of the film, or even I was the film-maker (I was just basking in my five minutes of glory merely by introducing the film)... I told them clearly that I am going to take Nathaniel Kahn to task for making me emotional watching an architectural documentary. I cannot remember the number of times I sneaked out my handkerchief in the darkness of the theatre to quickly mask the vulnerability of the critical architectural historian. The people I was talking to couldn't care less about my state, they were visibly moved people, they were as far as I could guess members of the general audience. They were all saying how spiritual the story was, how spiritual even watching the film was... they didn't get either a documentary or really architecture. They got a story, a moving story. And I can tell you, Nathaniel, that you moved people as only a master story teller can. And this is a true story. "Anyway, one should see this film in the evening so that you could come home, have dinner and promptly go to bed, and wake up in the morning pretending that nothing had happened. The film today ended at 2:15 or so, and I didn't know what to do afterwards. I genuinely felt listless. I told a friend that perhaps I should do something materialistic like go shopping to normalise myself, I didn't though. I had a long ruminative lunch, and later in the evening went to see 'Lost in Translation.' But that's another story." Yes, what does one do with a spiritually moving film about an architect in the foci of capitalist production? In an environment of mercantile and consumptive excess? No wonder -- something Nathaniel would also agree -- Kahn had an uneasy relationship with his homeland, even with his own city. The last fifteen minutes of the two-hour long film is about Dhaka, Buriganga river, madness on the streets of old Dhaka, crowds brimming on the South Plaza, and then looming through a misty winter morning, the phantom presence of Sangsad Bhaban. In that short span, Nathaniel has done a beautiful portrayal of Dhaka, and of the place of Kahn's work in the city, and how the project was really designed from the depth of the soul, as Hasina Choudhury reminded me after watching the film at one of the many sold-out screenings in Philadelphia. The climax of the film is really Shamsul Wares, an architect and professor of architecture, who gives an emotional soliloquy on the project (as I try to ponder the distinction between what is sentimental and what is emotional), and how Dhaka might have received more from Kahn than Nathaniel did. Nathaniel wanted his film to end with Dhaka, not so much because the greatest work of Kahn is in Dhaka, but his journey to find the elusive, mysterious architect father of his comes to an end on the lawn of South Plaza. Nathaniel is very clear: he found his father in Dhaka. What does that mean? To me, that's no longer an architectural question in its timid and conventional sense; it is what architecture meant for Kahn, part of existence, pulsating with the essence of life, in this case, the collective life that defines a city. Kahn believed in two things about a city: one, that nature and urban life may not be incompatible, and, two, a city is a place where a child walking on the street decides what she wants to do with her life. Sher-e-Bangla Nagar still promises Dhaka could be that city. (The following web site has information on the film: www.myarchitectfilm.com) Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, an architect and writer, currently teaches at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

|

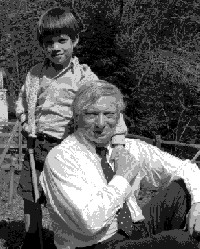

Father and son: Louis Kahn and Nathaniel |