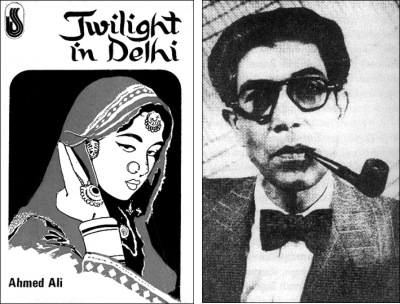

On Ahmed Ali and his Twilight In Delhi : the death of Delhi Muslim culture and the progressive movement in Urdu literature

Khademul Islam

Muslim rule in India began to derail with the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, and finally went off the tracks in the aftermath of the Sepoy Revolt in 1857. While Muslims generally all over India felt the wrath of maddened Englishmen, Delhi, then still the symbolic center of Mughal power, got it the worst. The sons and grandsons of the last emperor, the sorrowful Bahadur Shah Zafar, who had taken refuge in Humayun's tomb, were shot dead in front of him. An estimated 30,000 people died in the reprisals. Muslim nobles and commoners alike fled the city. Accounts of the time, and subsequent Urdu poetry, chronicle a bloody time. Mirza Ghalib in his Dastambu wrote that 'at the naked spectacle of vengeful wrath and malevolent hatred the colour fled from men's faces, and a vast concourse of men and women, past all computing, owning much or owning nothing, took to precipitate flight…' The Jama Masjid was used as a barrack for Sikh soldiers. The Zeenatul Masjid, the 'Ornament of Mosques' became a bakery. All houses, mosques, bazaars--including the legendary Khas Bazar and Urdu Bazar--within 448 yards of the Red Fort were demolished. Mughal Delhi was wiped out, while its culture, a high-flown Indo-Persian affair nurtured over centuries amidst the mansions, mohallas, lanes, houses and square miles clustered around the old court, barely limped on. With its ghazals and pigeon-flying, its courtyards and its langourous afternoons, its sky over Jama Masjid and tales of a glorious past, resentfully peering rheumy-eyed at the smart, spanking-new Delhi of the British Raj with its wide boulevards and European army uniforms, symbolic of a new order, being laid out beyond the confines of the ancient walled city.It is the decline and eventual death of this Delhi Muslim culture in the wake of the collapse of the Mughals, its death pangs, that Ahmed Ali's celebrated book Twilight in Delhi documents. Its opening sentences set the tone: 'Night envelops the city, covering it like a blanket. In the dim starlight roofs and houses and by-lanes lie asleep, wrapped in a restless slumber, breathing heavily as the heat becomes oppressive or shoots through the body like pain. In the courtyards, on the roofs, in the by-lanes, on the roads, men sleep on bare beds, half naked, tired after the sore day's labour. A few still walk on the otherwise deserted roads, hand in hand, talking; and some have jasmine garlands in their hands. The smell from the flowers escapes, scents a few yards of air around them and dies smothered by the heat. Dogs go about sniffing the gutters in search of offal; and cats slink out of the narrow by-lanes, from under the planks jutting out of shops, and lick the earthen cups out from which men had drunk milk and thrown away.' This is Muslim Delhi in 1910, where the aristocratic Mir Nihal stays with his extended household in the old quarter of the city, amid a network of lanes, in a house with a central courtyard at whose center lies not a silvery fountain, but a scraggly old date palm, with a henna tree at its foot and sparrows in its branches. The story follows the Nihal family over the next nine years, till 1919, through the love swoons and arranged marriage of his son Asghar, the Coronation Durbar of George V in 1911 (when 'motor cars which had hardly ever been seen before came into Delhi and raced on the roads…') through a series of extinctions: his prize pigeons (whom the Delhi Muslim aristocracy were fond of flying) eaten by a cat, his young mistress Babban Jan dies, the influenza epidemic of 1918 ravages entire neighbourhoods, and finally, comes the death of another of Mir Nihal's son, Habibuddin, which leaves the old patriarch 'on his bed more dead than alive, too broken to think even of the past. The sky was overcast with a cloud of dust, and one grey pigeon, strayed from its flock, plied its lonely way across the unending vastness of the sky…' Death in the old quarter, paralleling the dying culture and society all around it, overwhelms everything else in the book. Due to our bitter experience as East Pakistan, a large number of us associate Urdu with reactionary politics, quite naturally react badly to it as a language that was to be the chosen instrument for the suppression of our language and culture. It is linked in our minds with Muslim League, Jinnah, and genocide, its very tones reminiscent of blood and bayonet. Therefore it may come as a liberating surprise to quite a few of us, especially in a present-day Bangladesh where religious bigotry is attempting to suffocate freedom of expression and speech, to know that Urdu writers during the 1930s and '40s fought against these very same ideas and attitudes, expressed revolutionary ideals. That Ahmed Ali counted as one of the leading Urdu literary firebrands of the time. He was born in Delhi in 1910 into a cultured, traditional, urban Muslim family, which had lived in Delhi for generations. His first act of civil disobedience was at school, when he and a group of boys refused to wear medals distributed on the occasion of The Prince of Wales' visit and instead tied them to their shoes, for which they were caned soundly by their English principal. In 1932, after being educated at Aligarh (where his classmate was Raja Rao, another famous Indian writer in English) and Lucknow University, he started writing short stories in Urdu. In the same year, after teaming up with Sajjad Zaheer and Mahmuduzzafar, both of whom were Marxists freshly returned from Oxford, as well as Rashan Jahan, a doctor, the group brought out Angaray (Burning Coals), a highly controversial anthology of short stories. It is considered by most critics as the first example of progressive writing in Urdu. Angaray, with its openness to Western knowledge and literary forms, its intertwining of religious and sexual themes angered the mullahs and social conservatives. The story that gave the most offense was Sajjad Zaheer's Jannat ka Basarat ("Vision of Heaven"). The story is about Maulana Daud, who, at forty-nine, has taken a wife twenty years his junior. He devotes himself scrupulously to the observance of all Islamic rituals and, one night in the month of Ramzan, goes to his sleeping wife, whom he generally ignores, to find out where she has put his matchbox. Awakening but misreading his intentions, she grasps him about the neck and implores him not to leave, but to spend the night with her. Either because of fear of impotence or fear of God, Maulana Daud extricates himself from her embrace and returns to his prayers. During his prostrations, he falls asleep over the Koran and has a vision of heaven in which he sees himself about to engage in sexual intercourse with a houri. He is awakened at the moment of climax by his wife's loud laughter, only to find himself alone on his prayer rug, prostrated over the Koran. In the ensuing furor, the authors were labeled as "atheists" and "anti-Muslim." The British government promptly banned the book. As Ahmed Ali himself said later on, 'There were editorials on the front page and pamphlets written against us. Speeches were delivered in pulpits and mosques and some of the qassais [butchers] ran after us with daggers.' But the four writers fought back when the following year they published a joint statement called "In Defence of Angaray" in The Leader, (Allahbad), which also proposed a League of Progressive Authors, to consist of writers both in the vernacular languages as well as in English. In 1934, they founded the Indian Progressive Writers' Association in London, a group of about thirty or forty members, mostly students from London, Oxford and Cambridge, which held its first meeting in a Chinese restaurant. In 1935 Ahmed Ali and Zaheer attended the massive 1935 International Congress for the Defence of Culture in Paris, organized by Andre Gide and Andre Malraux to protest the rise of European fascism and attended by writers such as E M.Forster (where Ahmed Ali became friends with him), Aldous Huxley, Elya Ehrenberg and Boris Pasternak. In 1936 the two men launched The All India Progressive Writers Association, which committed itself to independent thought, religious harmony and a socialist, egalitarian creed. Its first meeting was presided over by no less than Premchand. It soon came to include such literary luminaries as poet-critic Firaq Gorakhpuri, the charismatic Congress politician-poet Maulana Hasrat Mohani, Mulk Raj Anand, Ismat Chughtai, Krishen Chander, Saadat Hasan Manto and Akhtar Husain Raipuri. The organization's influence was felt in nearly all of the major Indian literatures, specially in Urdu, Bengali and Maiayalam, where they were far-reaching and lasting. Differences, however, cropped up between the creative writers and some of the more doctrinaire members in the organization over what constituted 'progressive' literature and the wholesale adoption of the Soviet literary school of 'socialist realism.' Ahmed Ali refused to subscribe to such ideas. Finally, matters came to a head, and Ahmed Ali broke away from the Progressive Writers Association. It was then that he wrote Twilight in Delhi, which developed out of his celebrated Urdu short story 'Hamari Gali’ set in Delhi.. Thereafter Ahmed Ali served as professor and Head of the English Department, Presidency College, Calcutta. After Partition in 1947, he went to Pakistan and joined the foreign service, from which he was retired in the early '60s by Ayub Khan's government. He remained a prolific writer, producing essays, short stories, novels and poems, translations (his poetic translation of the Koran into English was widely praised), and lecturing at American universities till his death in Karachi in 1994. Which brings us to the question: why did Ahmed Ali write the novel in English? The short answer is that he wanted to reach a different, wider Anglophone audience. And because he wanted to challenge the dominant imperial narrative on its own terms by telling a tale of a society to British readers largely ignorant of it, even though they had aided considerably in its downfall. It took persistence and courage on Ahmed Ali's part, for when he arrived in London in 1939 with the manuscript in his hands, he was refused permission to publish it on grounds of that age-old bogey: sedition. He then took it to E. M. Forster and Virginia Woolf, who lobbied for its publication, and finally it was brought out by Hogarth Press in 1940. Forster said of it: 'It is beautifully written and very moving. The detail was almost all of it new to me, and fascinating. It is a sort of poetical chronicle. At the end one has a poignant feeling that poetry and daily life have got parted, and will never come together again.' Edwin Muir. in his review of the novel in The Listener, wrote that 'The atmosphere in which the story passes...has a striking resemblance to that of the French Romantics: there is the same exaltation of feeling…(the) union of horror and tenderness and something resembling romantic pity...The writing produces a curiously pictorial effect, yet is itself as clear as water. The end, where innocence is drowned by experience, is intensely moving.' What Muir and Forster were referring to was that the English language as evolved by Ahmed, in order to depict a fallen world of ghazals and nightingales and courtyards, itself seemed ghazalized, so to speak, infused not only with Delhi Muslim motifs and metaphors, but changed to a degree where the pace and contours of the sentences themselves reflect Delhi's hot winds and beggar cries, where Time, seen in terms of the collapse of an entire civilization is, to paraphrase Husain Askari's words, so intensely felt that it transcends mere personal sorrow. But Ahmed Ali's progressive instincts were never too far below the surface, and the book also addressed its Muslim audience by chronicling how by refusing to change, by clinging to the past it was beggaring itself intellectually. In the book is depicted unblinkingly a society and culture unable to recognize its decadent pursuit of courtesans and suffused with a perpetual strain of effete song and dance, that refuses to adapt to modern conditions, which resists its own reformers (Asghar is denied permission to study at the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College, or Aligarh University, then thought by conservative Muslims to be the very den of a fearful westernization), a society where rote learning and superstition have a firm grip, where its young quote ghazals at every turn and its old are obsessed with alchemy, where everything exists and is interpreted within the frame of the past, where bloodlines and status derived from it dominate social transactions. A society whose wellsprings have run dry, and therefore is condemned to die a lonely death. But, and most crucially, as is true with all superior fiction, these truths are presented gently, wistfully, tenderly, and unforgettably through the consciousness of its principal character, Mir Nihal. Ahmed Ali remained faithful to his youthful progressive convictions till the last, when at age 75 he penned what might be termed as the South Asian Muslim progressive's credo: 'I am still a progressive, and try to face the actualities of life, and look at it with unclouded eyes, untrammelled with baseless conservatism or ideality, or the shibboleths of our own making, the tin gods who sit in judgment over our freedom of thought and expression, and restrain us …from marching towards the goal of higher perception and purpose of life, the intenser realisation of man's destiny for which he was ordained from the beginning of creation.’ How many of us, living in these fraught times, can say the same about ourselves? Khademul Islam is literary editor, The Daily Star.

|

|