BookReviews

On 420s, 16th Divisioners and crooked oak branches...

Khademul Islam

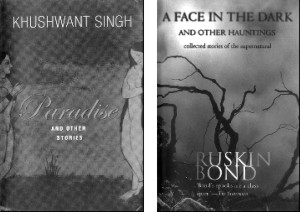

Paradise and Other Stories, Khushwant Singh, Penguin Books India, 2004, New Delhi, pp+239 pp. A Face In The Dark and Other Hauntings, Ruskin Bond, Penguin Books India, 2004, x+197 pp. I first got acquainted with Khushwant Singh in a most unlikely setting. It was November 1972, and my family was on the lam. We were one of nine or ten Bengali refugee families who had escaped from Pakistan through Afghanistan and now were at Delhi's Palam airport. Though at Kabul we had been issued Indian visas on our Pakistani passports and assured of entry, yet we were nervous about it. Would the Indians really let us in? Would we be hassled by uncomprehending officials, be stranded in a no-man's land at the airport? It had been a tiring flight, we had already blown much of our cash reserve, we were still a long way from Bangladesh and God only knew what lay ahead. The tension in our elders spread to the children and we too fidgeted when it was our turn to go through customs. The Indian customs officer was an older man, a senior officer in starched white, who, however, surveyed us kindly. 'Aha,' he said in English, 'in transit, eh?' 'Yes,' my father, I and my brother chanted out in unison. 'Glad to be in India?' he asked pleasantly while flipping through my parents' passports. 'Y-e-e-e-s-s!' 'Tell me, boys,' he said, sweepingly including my sister in that gendered term, 'this has been quite a holiday, right?' 'Yes.' Our nervousness abated, the mercury dipped low. We realized that the customs people had been told to 'look after' Bengali refugees passing through Delhi. He barely glanced inside our crammed suitcases, which was the pitiful sum of our earthly possessions then, and chalked them for freedom, all the while bantering with us. But just as we were about to walk away from him, towards a sunny Delhi beckoning to us through glass panes and doors, he seemed to think of something and called out to my father, 'Just a minute, please.' What now? The mercury rose. 'Could I take a look at your passport again?' Oh shit! My father handed over his passport. The customs officer took it and opened it, then said, 'Right, you were in the information ministry?' 'Yes.' 'Journalist?' 'Well, yes, sort of.' With a broad smile creasing his face, the customs officer put the thumbs and forefingers of both hands on the waistband of his trousers, hitched them up, rocked back slightly on his heels, and asked, 'Then you have heard of Khushwant Singh? He writes in our newspapers.' My father was slightly startled, but said 'Yes, yes, I have.' The rocking stopped, the smile stretched further, the fingers came out of the waistband. 'He,' he announced with lavish pride, 'is an in-law of mine.' 'Oh, I see...' Now it was my father's turn to grin. 'I thought you'd have heard about him.' 'Of course.' They smiled at each other for a few more seconds. Then the customs officer leaned forward and shook my father's hand. He then looked at the rest of us, raised his other hand, waved it and sang out, 'Good luck!' We waved back, then literally skipped out of the gates of Palam airport. Over the decades since then Khushwant Singh has become an icon, and so it was not startling to note that Indian newspapers had given his latest work, Paradise and Other Stories, quite a few column inches when it came out a couple of months back. Of course, coverage of the book launching had not been hurt by the fact that big names showed up: the elusive Vikram Seth, the historian Romila Thapar, the Indian prime minister's wife and daughter. But as usual it had been Khushwant Singh who had taken center stage. He declared that he had to get this book of short stories ( a return to the form after many years) off his chest, had to write it in order to give vent to his anger at uniquely Indian charlatans and poseurs: mystics, astrologers, fake holy men, venal sadhus, lusty pirs and the like. 'You may or may not like it,' he said, 'but that's me. I have got the venom out of me.' Khushwant has always hated cant, hypocrisy and chauvinism. And he has always written, and said, pretty much what he pleases. When the BJP was in power, and he was out promoting his autobiography Truth, Love and A Little Malice a few years back he loudly told an interviewer, without turning a hair (or turban to be more specific) that when the RSS spoke of restoring India's lost honour, their 'targets are really the Muslims. They are the Jews, what the Jews were to the Nazis.' Bang! You could hear that shot ricochet through Delhi and beyond. In his autobiography he almost offhandedly threw out that 'A common prostitute renders more service to society than a lawyer. If anything the comparison is unfair to the whore.' Bang, bang! And there's plenty more of these fusillades, scattered throughout his innumerable articles, columns and books. But at 90, you would think the Grand Old Man would sheath his khanda and not care about keeping his powder dry. Not so. In Paradise and Other Stories he goes after Sanskrit texts, saffron-coloured bunkum, horoscope-readers, gurus, ashrams and pirs and charso beeses and soothsayers, after every shibboleth and false idol he can think of, all with his trademark relish. The best story among the lot is undoubtedly 'Life's Horoscope', where the brand-new wife of amateur astrologer and scholar of ancient Hindu texts Madan Mohan Pandey upsets his calculations by demanding the real thing, not the dead formulas of Kama Sutra. Which leads me to forewarn Bangladeshi readers who have not read much of Khushwant to be prepared for his raciness--the Grand Old Man has also been called the Dirty Old Man by some Indian commentators. More than most writers, he has never cared for the middle-class taboos and guilt that can make so much English writing in South Asia excessively mannered and fusty. In appropriate doses, it can be refreshing. It can also make you wince, as when in the autobiography he noted in unnecessary detail his late wife's toilet habits. But the language, the free-for-all engagement with risqué topics, is an integral part of the package. As more than one reviewer has noted, Khushwant is Khushwant, take him or leave him. In this particular volume, one has to admit that the book's characters, especially the 'phoren' ones, tend to be caricatures, as, say, the American mother whose boyfriends, and conversations with her daughter ('Howya doin', hon?' ) are straight out of a bad sitcom. This is because in Khushwant's fiction characters are sacrificed on the altar of plotting, which are perhaps best described as a headlong rush--the author is in a hurry to prove a point. However, where he most fails to, ahem, rise to the occasion is in his prose style, which can veer between the 10-rupee bodice-ripper ('Our eyes met; his were as large as a gazelle's. His gaze drew me towards him. It was as though I was hypnotized.') and straight journalese ('They supported one or the other of the Hindu fundamentalist parties.') If you can stand yards and yards of this stuff, this book's for you. And Khushwant no doubt would probably retort that he never did aspire to the condition of literature. There's nobody here in Bangladesh writing in English even remotely like him. More's the pity! Just think of all those fraudster mullahs and poseurs and 420s and 16th Divisioners and trickster politicos standing deliciously unmarked waiting for somebody to take a sledgehammer to them! * And language is what you notice most in Ruskin Bond (another writer who has been around for decades, having written over a hundred short stories, essays, novels, and more than thirty books for children), when you pick up A Face in the Dark and Other Hauntings straight after Khushwant Singh. He is the superior writer, with a far better ear for English sentences. Here he is at his best describing Indian hill stations during the evening or at night, as in these wistful ghost stories for the younger crowd, tuning the mood and atmosphere appropriate for supernatural goings-on, when men are 'stalked by the shadows of the trees, by the crooked oak branches reaching out...', or, 'I was returning home along a very narrow, precipitous path known as the Eyebrow. A storm had been threatening all evening. A heavy mist had settled on the hillside. It was so thick that the light from my torch simply bounced off it. They sky blossomed with sheet lightning and thunder rolled over the mountains.' Where live the barking deer and blue, long-tailed magpies. Which is perhaps natural given the fact that Bond grew up around Dehra Dun, and has made his home in the hill station of Mussorie, way up in Arunachal Pradesh, not very far from where Jim Corbett lived and hunted. And given the history of hill stations, founded and sustained by the officers of the British Raj, it is therefore not surprising that a genteel, old-fashioned Anglophilia pervades the book's well-contoured tales, where Kipling and Sherlock Holmes and harrumph-ing ex-army colonels make appearances. And which actually makes this little book haunting in a way perhaps not foreseen by its author. *Note to readers: A Penguin book sale is currently being held at Etcetera bookstore in Gulshan. Khademul Islam is literary editor, The Daily Star.

|

|