Jumping Ship: Three Bangladeshi Diaspora Novels in English

Kaiser Haq

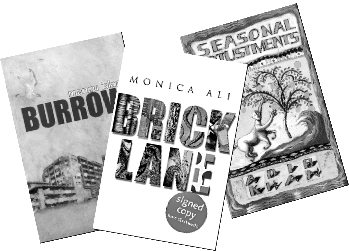

On the map of South Asian anglophone literature, Bangladesh is very much on the fringe, more so than Pakistan or Sri Lanka. All the readable homegrown Bangladeshi poetry, fiction and non-fictional prose in English could be accommodated between two covers. There are good socio-political reasons for this. Though Bangladesh used to be the larger part of Greater Bengal, the most Westernized and cosmopolitan region under the Raj, the cross-border emigration of the predominantly Hindu zamindar and professional classes following the 1947 Partition soon turned it into the more provincial of the two wings of Pakistan. East Pakistan's agitation against what was perceived as an unequal partnership in the newly formed Islamic Republic was reinforced by lingual nationalism, which, after the bloody independence war of 1971, produced a nearly monoglot state proud of the thousand year-old Bengali literary tradition that it shares with West Bengal, Tripura and parts of Assam and Meghalaya. The country's self-appointed cultural commissars ritually inveigh against apasanskriti--"perverse culture"--by which they mean popular Western and Bollywood culture, and disapprove of attempts to produce an anglophone Bangladeshi literature. Individual Bangladeshis still trying to write in English--they could be counted on one's fingertips--work in isolation. And yet this is not the whole story. English-medium schools flourish, offering pricey education leading to the British "O" and "A" levels. Their students, who belong to the upper-middle and wealthy classes, either go abroad for higher studies or go up to a private university at home. Some of them have literary interests and are aspiring anglophone writers. Among readers of English-language books there is a longing to see Bangladeshi English writers attain the kind of success that so many Indians have achieved. And so when Monica Ali gained instant celebrity with Brick Lane, many in the land of her birth were thrilled; soon pirated editions of the novel as well as a Bengali translation were being peddled on pavements and at traffic lights. But while most were obviously fascinated by Ali's representation of Bangladeshis, there were a few bitter dissenters, once again highlighting the perils of literary mimesis. Monica Ali is the lone celeb of diasporic anglophone Bangladeshi literature, which is even less in volume than homegrown Bangladeshi English literature. There are in fact only two other diasporic Bangladeshi fiction writers we can consider, Adib Khan, whose debut novel Seasonal Adjustments (1994), won the Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best First Book (his two later novels are imitative magic realist fantasies and may be safely ignored), and Syed Manzurul (Manzu) Islam, who has followed up his collection of stories, The Mapmakers of Spitalfields (1997) with a novel, Burrow (2004). But these three writers demarcate a fairly extensive fictional terrain and highlight both the general traits it shares with the rest of the subcontinental literary diaspora as well as its peculiarly Bangladeshi qualities. Of particular interest is the picture of Bangladesh that emerges in the works of these writers. Tabish Khair's Babu Fictions (2001) will long be a useful reference point in discussions of subcontinental anglophone fiction, particularly for its insights into alienation, exile and the language question. Our three writers conform neatly to the upper-middle class, English-educated type described by Khair. Adib Khan took a degree in English from Dhaka University in 1973 before emigrating to Australia, where he studied at Monash University and then went into teaching. Manzu Islam is the son of the late Syed Nazrul Islam, Acting President of Bangladesh during the 1971 independence war and subsequently a cabinet minister, who was assassinated by the perpetrators of a coup in 1975. Manzu Islam went to England the same year, studied Philosophy and Sociology and then literature at the University of Essex; he is currently lecturer at the University of Gloucester. His first book was The Ethics of Travel: from Marco Polo to Kafka (1996), which critically examines the responses to alterity in Western travel writing. Both Adib Khan and Manzu Islam, then, belong to a category that has become quite common on the global--and not just the subcontinental/postcolonial--literary scene, the writer-academic. Monica Ali stands apart in more ways than one. Born in 1967 in Dhaka to a Bangladeshi father and an English mother, she and her brother were taken by their mother to England during the 1971 war. Her father joined them a few months later, and after the unavoidable difficulties of a transitional period, the family settled into a middle-class existence. Though Monica Ali and her brother spoke only Bangla when they left Dhaka, they soon completely lost their first language; this curious fact distinguishes her not only from other Bangladeshi writers but from most subcontinental writers as well. After school at Bolton, she read Modern Greats (PPE) at Oxford, then worked in publishing. The idea for Brick Lane occurred to her when she came across the MS of The Power to Choose (2000), a study of garment workers in Bangladesh and Banglatown, London, by Naila Kabeer, a Bangladeshi sociologist teaching at Sussex University. Adib Khan's Seasonal Adjustments exhibits "the dual alienation" that Khair identifies in the "returned natives in Indian English fiction." In the case of Iqbal Chaudhary, Khan's protagonist, one could speak of triple alienation: first from his native land, next from his adopted homeland, and finally from what the former has become during the years he has been away. Eighteen years after he had emigrated, he visits Bangladesh with his daughter Nadine at the urging of a New Age faddist: "Go home . . . where you really belong . . .. Heal yourself in your spiritual womb." In the book's very first paragraph Chaudhary arrives without warning at his ancestral village. He muses that if he had sent a message to his cousin Mateen, there would have been "dancing girls sprinkling me with rose-scented water and scattering flowers at my feet." This is pure Orientalist fantasy: things might have been different when Chaudhary's ancestors were decadent zamindars, but nautch girls in a conservative Bangladeshi village circa 1990? Really! Chaudhary's portrayal of his village is in line with Orientalist stereotyping: "I can discern no changes in the years I have been away." No changes in a Bangladesh village in two decades following the independence war? Bangladeshi villages have probably undergone more changes during this period than in the previous two centuries! For the first time in history, villagers throughout Bangladesh (and not just in particular districts like Sylhet or Noakhali) began to look for opportunities for emigration or jobs as migrant labour. Chaudhary, however, can only see Bangladesh in terms of prefabricated generalizations, stereotypes, caricatures. The sole purpose of his narrative is self-aggrandizement. He has evolved from an English-medium educated Bangladeshi alienated from the masses to a foreign citizen alienated from the whole world. But there is a crucial difference between the two forms of alienation. The alienation he feels in Australia, apart from the complication added by race, is something he shares with other citizens of that country; it is the outcome of the unavoidable anxiety of a secular, rational, consumerist l'homme moyen sensuel. But vis-a-vis Bangladesh the alienation is absolute. Bangladesh is a hideous background against which he can admire himself. The country's embarrassing poverty, described with a fanfare of cliché s, becomes a source of moral satisfaction as he looks beyond himself "at the bleeding rawness of bare existence. It is an expansive experience, a forced act of selflessness to be able to reach out and feel a pulse of suffering not my own." From the village Chaudhary moves on with tourist brochure thoroughness to deal with well-known varieties of Third World iniquity and grotesquerie: a charlatan of a Pir, guests at a feast gorging themselves with Yahoo-like abandon, the oppression of military rule, the hideousness of lepers who are said to infest Dhaka in their hundreds (actually there are hardly any), aggressive beggars who promptly mug Chaudhary. The Bangladesh independence war plays a crucial role. While it raged Chaudhary was carrying on with the girl friend of a friend who had gone to fight against the Pakistanis. The end of the war, sadly, did not bring immediate peace. There were sporadic reprisals against post-Partition Bihari settlers who had collaborated with the Pakistan Army, and Chaudhary's decision to emigrate was prompted by outrage at such barbarity. The mention of the reprisals is in itself commendable, since there is a tendency among Bangladeshis to elide them, as if they were negated by the fact that the Pakistan Army and its collaborators had perpetrated much greater atrocities. Chaudhary's laudable moral outrage, however, is not only aimed at a particular phase of history one that lasted a few weeks; it links up with the other negative observations to justify his decision to be a migrant: "Do you know what it means to be a migrant? . . . You can never call anything your own. But out of this deprivation emerges an understanding of humanity unstifled by genetic barriers. No, I wouldn't have it any other way. I have had my prejudices trimmed to manageable proportions . . .. Difficult for you understand (sic), isn't it? You, who allow yourselves to be blinded by your pride in a singularly blinkered tradition which fertilises the grounds of bigotry." The Mapmakers of Spitalfields, as Sukhdev Sandhu points out in his review of Brick Lane, was the first work of fiction about Banglatown (London Review of Books, 9 October 2003). The stories set in Banglatown give a sense of its milieu, despite their curious use of language: "avoided each other's shadows and haunts"; "Have you eaten your head or what?" (Bangla idiom literally translated). Problems of language use remain in Burrow, which is otherwise a more ambitious and sustained performance. The protagonist Tapan Ali has been sent by his anglophile grandfather to England for higher studies. When he is halfway through his final year at university his grandfather dies, leaving him with the prospect of returning to Bangladesh as soon as he gets his degree. He realizes that "he wanted to stay in England. He had nobody and nothing in Bangladesh to go back to. Here he had his friends. Besides, the kind of life he wanted to live was only possible in England. He wanted economic independence, anonymity and no responsibility for anybody or anything." This self-regarding avowal is the premise for the narrative that unfolds. Adela, a fellow student with whom Tapan has had a casual affair, suggests a marriage of convenience that should eventually get him British citizenship. (Her name alludes to A Passage to India; the connection is made explicit at one point.) Marriage alters the relationship, first sweetening it into a mellow romance, then suddenly souring it, precipitating a separation. The Home Office turns down Tapan's application for immigrant status and he becomes a fugitive moving from one hideout to another in Banglatown, helped by a tightly-knit group of friends. With one of them, Nilufar Mia, a university educated social activist, he has an intense relationship that could very well put his life back on an even keel. But Adela meanwhile has given birth to his son (unknown to him she was pregnant when they broke up); suspended in an emotional limbo, he cannot bring himself to ask her for a divorce so that he can marry Nilufar. He becomes increasingly spacey, prompting Nilufar to betray him to the immigration Police; she feels that it's best if he is sent back to Bangladesh before he goes completely round the bend. But for Tapan the entire experience has a very different complexion. He feels a sense of community in Banglatown, which at this juncture has been galvanized into resistance against racist thugs. Alone in his hideout he relives memories of his Bangladeshi village--central to them is the diminutive, skinny Vatya Das, a barber who had been a terrorist in the anti-colonial struggle and for twenty years a fugitive from the colonial Police. Tapan looks back on him as a kindred spirit: both he and the Vatya are moles who have hidden in burrows. Unlike Vatya, Tapan's late grandfather has collaborated with the colonial rulers and has opprobrium duly heaped on him: "An arse-licker of the British Raj." The account of colonialism never rises above the tritely simplistic: "they went around naming our things like they invented them…their greed is almost as boundless as Allah's bounty?…after naming, they pocketed our things like they were inheritances from their forefathers." The portrayal of Vatya Das introduces magic realism, but only half-heartedly, so that the reader is discomfited rather than transported. Just as Tapan identifies himself with the communist Vatya Das, the latter feels a kinship with the martyred sufi Hajjaj Al-Mansur. Since in mysticism the way up and the way down are one and the same, one shouldn't be surprised that Tapan wants to burrow till he reaches "the airy depths of things," when he will be able to overcome gravity and fly. Tapan steadily becomes delusional about flying--and is in a state of elation when finally nabbed. There are other burrowers: the colonial "Bombay Bill," who is at home in the maze of London's sewers, and the anti-colonial Masuk Ali et al, who quixotically tunnel towards the Tower of London in order to get back the Kohinoor diamond, a symbol of India's pre-colonial glory. Despite the novelistic investment in the subjective drama of Tapan Ali, the book's core remains the portrait of the Bangladeshi immigrant community of ship-jumpers, bauls, spiritualists and streetwise spivs. They claim to have come to Britain to escape hunger, a point made by both Tapan and Nilufar in a peculiar idiom literally translated from Bangla: "I suppose we wanted to better ourselves. Improve our life chances. Some of us simply wanted to eat. I don't have to remind you how things are back in Bangladesh" (Tapan). In childhood Nilufar heard a madman shouting," Go England. Good eating. Plenty, plenty rice. Plenty, plenty meat. England, good eating." The delineation of Banglatown is ultimately premised on the assumption that in Bangladesh things are too bad to permit one to lead a normal life; the pressures of life in a hostile environment are preferable to the problems in the mother country. Even in the fey state in which Tapan is nabbed, he affirms, "Here, right here, in the belly of London, is my home too." Unlike the other two novels, however, Burrow does not provide details about contemporary Bangladesh. Brick Lane/ is essentially the story of Nazneen, born in 1967 in a village in Mymensingh (she shares her birth year and ancestral village, Gouripur, with her creator), and married off at eighteen to a much older man, Chanu, who transplants her to a dismal housing estate in Tower Hamlets in London's East End, where she slowly and painfully acquires confidence in her own selfhood. Though in an altogether different class than the other two novels, it is not without its problematic side. I am not referring to the virulent protest by certain Banglatown leaders who alleged that the novel besmeared the image of their community (the protesters confused realism with lack of sympathy) but the presentation of Nazneen's ill-starred younger sister Hasina. Strikingly good-looking and wilful, she elopes with her beau. But the romance fades rapidly, the husband turns out to be a wife-beater, and Hasina runs away to Dhaka to join the vast army of garment workers. The perils of a pretty sweatshop worker are graphically illustrated: Hasina is slandered, sacked, sexually exploited. She eventually becomes a domestic and the last we hear of her is that she has eloped with the cook. She is a natural-born survivor. As Nazneen sums up, "She isn't going to give up." It's an all-too-common tale but in presenting it through Hasina's letters to Nazneen the author runs up against a technical problem. As Hasina has even less education than her sister, she is supposed to write imperfect Bengali, which is impossible for Monica Ali to imagine and translate. At her editor's suggestion she circumvented the problem by devising a bizarre pidgin that demands of the reader an effort to willingly suspend disbelief. The technical failure becomes more glaring if one peeps into Naila Kabeer's The Power to Choose, which makes extensive use of interviews with garments workers, conducted in Bangla and translated into simple English. They are more convincing than Hasina's letters largely because the bland English used does not draw attention to itself, whereas the odd idiom of the latter makes the reader stumble. By way of illustration let me juxtapose a few lines from an interview in The Power to Choose with Monica Ali's pidgin adaptation: The best purdah is the burkah within oneself, the burkah of the mind . . .. You see, if I keep my fingers closed into a fist, you cannot open my hands, can you? Even if you try, it will take you such a long time, it will not be worth your while. Similarly, if I maintain my purdah, no one can take it away from me.

(The Power to Choose)

Pure is in the mind. Keep yourself pure in mind and God will protect. I close my fingers and make fist. I keep my fingers shut like this you cannot open my hands can you? I say like this to her. Even you try it take such long time it not worth it for you. Same thing my modesty. I keep purdah in the mind no one can take it.

(Brick Lane)Hasina's letters perform the critical role of delineating the condition of Bangladesh; what comes across painfully is a state of anomie. And yet, unlike the other two novels, Brick Lane does not quite write off the country, and till its open-ended finale depicts resolute attempts to cope with the chaos. Besides Hasina, there is Chanu, back in Bangladesh, while Nazneen stays back in Banglatown with their daughters. The girls are sure that their father will soon tire of Bangladesh and return, but meanwhile there is talk of a family holiday in the old country. In the last scene Nazneens's daughters take her ice-skating. When she protests that one can't skate in a sari, her friend Razia quips: "This is England. You can do whatever you like." This might seem like as a slogan for what the Tories notoriously described as the Race Relations Industry. But it reveals a significant fact about expatriate Bangladeshis: the men dream of return, but not the women, who even as second-class citizens enjoy rights denied them in the mother country. The portrayal of Bangladesh in our three novels is compatible with Time Magazine's recent characterization of it as Asia's "most dysfunctional state." But, as Aristotle would have pointed out, the article describes a contingent historical situation, whereas the novels make an essentialist statement. Brick Lane just about avoids the pitfall, but not the egregious Seasonal Adjustments nor Burrow. Both condemn Bangladesh to perennial solitude in a remote corner of the banana republic of postcolonial letters. The writerly freedom to do so cannot be denied, but it is the critic's task to point out the implications of the choice. If one may end with a metaphor, in these novels Bangladesh is a ship beset with all sorts of problems--sea-sick passengers, disaffected crew, plague-carrying rodents, what have you. A few crew members jump ship, but they are no Lord Jims. Kaiser Huq teaches English at Dhaka University. This article was first published in the Nov-Dec 2004 issue of Biblio (Delhi) and 'Prince Claus Fund Journal #11' (The Hague, Netherlands), which were devoted to the theme of 'asylum & migration'.

|

|