Letter from Mumbai

The beginnings of Poetry Circle

Menka Shivdasani

Rummaging through my bookshelves the other day, I found a slim white volume that has sunk without a trace in Mumbai's poetic spaces. It's called After Kalinga and Other Poems and has been written by Akil Contractor, a friend I haven't seen for many years. When I met him last, he was running a family business making ink; in between the demands of manufacturing it, he found the time to use some of it for his own poetry.It was this seemingly insignificant volume of poetry, and another called Spirit Song, also by Akil, that proved to be the catalysts for a group that has survived for close to two decades. With too many other pressing demands, it has sometimes felt like a shaky survival. The fact is, however, that next year, 2006, marks the 20th anniversary of the Poetry Circle in Mumbai. Sometime in mid 1986, another friend Nitin Mukadam, called me out of the blue. "There's this chap I know who's written two books of poems, and he's asking, 'Is there an audience for this sort of thing?'" Nitin said. "Is there anything we can do about it? " In those days, Nissim Ezekiel used to run the Indian P.E.N, organizing literary events once a month. If you were lucky, you even got published in the P.E.N. journal that he edited. Kavi, edited by Santan Rodrigues, was still around as well, battling various odds, as 'little magazines' tend to do. Yet, if you were a young poet, taking your first uncertain steps in the minefield, you were unlikely to find much support. Nissim Ezekiel was always a willing listener, and a sharp but supportive critic, but there were few spaces where young people could meet to share their work and receive the much-needed feedback. Nitin, Akil and I met at the Parisian Restaurant, a spacious and quiet café in the busy commercial Fort district downtown, and discussed the possibility of starting an organization for young poets. Nitin was the practical one; as an advertising man, he knew the importance of 'branding'. "Poets may not necessarily think about these things," he said, "but it would make all the difference if the organization had a letterhead and logo. If you want a newspaper to carry an announcement about a meeting, they will take it far more seriously if the note comes on a letterhead." We decided on the Yin-Yang symbol, representing harmony, balance and perfection, and Nitin got his artists to put together the logo and the letterheads. Doing this was not as easy as it would be today; the computer revolution had not yet transformed the industry. He was right, however; when the newspapers carried our first announcement, the conference room in his office at Gannon Dunkerley was jampacked. Clearly, despite all we said about nobody being interested in poetry, there was a deep-rooted need somewhere. In fact, there was some disappointment when people realized that this first meeting was purely administrative; they had come with poems they wanted to read out and share. Logos and letterheads were of course only the initial, very basic steps. What was more crucial was actually drawing the audiences. I had been attending poetry readings for long enough by then to be extremely skeptical about anyone wanting to come and hear young poets. Our initial strategy, therefore, was to have one senior poet reading, and a few of us non-entities sharing the platform too. As someone who had had the good fortune of meeting Nissim Ezekiel, and through him, many other young poets, I was in a position to pass the word around Among those who joined us at that time were R Raj Rao, now a professor at Pune University and author of several books; Marilyn Noronha, a banker; Charmayne D'Souza, a counselor; Prabhanjan Mishra, a customs officer; and T R Joy, a professor of English literature. We were young and enthusiastic, and there was much to do. Nissim Ezekiel provided unstinting support, including at a later date, a space at the P.E.N. for our meetings every second and fourth Saturday. The initial discussions that Nitin, Akil and I had took place in May 1986; it was on October 3, 1986, that we held our first 'big' event. Dom Moraes, winner of the Hawthornden prize at age 19, had been making news in the city; could we possibly dare to ask him if he would read at a function that we organized? Dom had, in fact, been in poetic hibernation for 17 years, but to our amazement, he agreed to do a reading--the first, he told us, that he would be doing in all those years. The event, at the Cama Hall in Mumbai, attracted close to 100 people, more than twice the number I had ever seen before at a poetry reading in the city. Dom subsequently wrote a column in a Sunday paper about that evening, speaking about the 'culture vultures' in their 'backless cholis', and about how young people, unimpressed by such artifice, simply created their own events. Referring to Poetry Circle as a "serious organization", he wrote in a newspaper column: "Every such association of young writers will eventually produce one or two professionals, and they should be encouraged." Those were heady days, and help came in from unexpected quarters. Artists Centre, which had a large art gallery, offered us their space, and apart from our regular meetings, we held several special readings by poets such as Jayanta Mahapatra and Gieve Patel. There were workshops, including one conducted by Sharon Diane Guida from the University of Iowa; a talk on women writers by Adele King, and even a multi-lingual poetry reading 'under the stars', with Dr V S Venkatavardan, then director of the Nehru Planetarium, offering us the entire space for a special programme. There were also some trips outside Mumbai, where the young poets could share their work in natural environments. In its May 31, 1988 issue, India Today, a leading newsmagazine, had said: "The Poetry Circle, with similar groups in cities around the country, is the most visible symbol of a new revival of Indian poetry in English sweeping the literary scene." In the first year, we organized a competition, with prize money coming from our own pockets. It was meant to be a small local event, but when the newspapers announced it, entries came in from all over the country, and even Dubai! For the first anniversary function, we wanted to do something special. Could we ask Kamala Das to come in from Trivandrum for a reading? Of course not! Where was the money? Who would pay for her air ticket and the hotel room? And would someone of her stature think we were worth her time anyway? We had heard vaguely that she had a son working for The Times of India, so decided to drop in at his office. "We wanted to call your mother for our anniversary function," we told him a little hesitantly. "But we were wondering how to manage it." He was delighted. "Don't be silly," he said. "She's my mother, I'll be happy to do anything to bring her here. And of course, she will stay with me!" And so, Kamala Das came to Mumbai for the Poetry Circle. Sydenham College gave us their auditorium, gratis, and Dom Moraes was among those who attended. Those who still make it to the monthly Poetry Circle meetings today will never have heard of the support provided by an adman called Narain Sadhwani. I wanted to bring out a newsletter and didn't know how. Then one day, someone took me to Sadhwani's home-cum-office, and I found three or four computers there. (Remember, the computer revolution had yet to hit us, and if you owned one, you treated it like God!). I asked him, a little nervously, whether he would put together a newsletter for us--on commercial terms, of course. (Though who knew where the money would come from, if we actually had to pay him!). Sadhwani--or Sadi, as he was known--was not the sort to particularly mince words. "I don't do that sort of s____!" he said, glaring at me. Then he added: "But if you like I will show you how to use a computer and you can do it yourself." And that's how our very first, extremely amateurish, and very short-lived newsletter, 'I to I' was born. The well-known graphic artist Sudarshan Dheer designed a dozen covers for our use, and another friend, Rajesh Chaturvedi, printed the newsletter for us. None of them expected anything in return. Much later, the Circle was to bring out a magazine called Poeisis, edited by Prabhanjan Mishra and T R Joy. Over the years, there have been many people who have nurtured the Poetry Circle in different ways--Nissim Ezekiel, Marilyn Noronha, Charmayne D'Souza and R Raj Rao, among them. The Circle has also seen the emergence of younger, extremely talented poets like Ranjit Hoskote, Jerry Pinto and Arundhati Subramaniam, who have contributed significantly to its continued existence. If it lasted so long despite all its ups and downs--it was because the Circle had grown far beyond the three people who originally started it. Many members of the Circle have gone on to publish their collections, and build very strong reputations for themselves. In the introductions to some of their books, they have acknowledged the role that other Circle members have played. The restaurant in which we had our first discussions has long since become a bank, and many of us have moved on to more responsibilities than we had in those early heady days. The Circle, however, still meets once a month--and, it must be said--with great difficulty, in a city where space and time are at a premium. Nissim is no longer with us; neither is Dom, and the world seems like a very different place. New groups have come up in these two decades. There is Loquations, started by Adil Jussawalla and now coordinated by Jane Bhandari, among others. Bengali writer and editor Mandira Pal and Malayalam poet P B Hrishikesan have brought together poets from different languages; the second meeting was held last week, on Christmas Eve. Twenty years ago, when the Circle began, people had to come from across the city to a central point for meetings. Now, technology has changed all this; ask Caferati, which organizes 'read-meets' at different venues. Caferati started as an online forum, and continues to be a very vibrant one. The Internet has transformed even our literary spaces, and who knows what changes the next 20 years will bring? I hope I am around to see them! Menka Shivdasani has published two volumes of poetry: Nirvana at Ten Rupees and Stet.

|

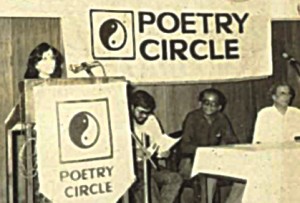

Menka, Akil, Aroop and Nissim Ezekiel |