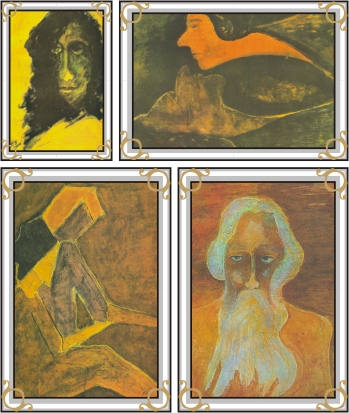

145th Birth Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore

The modern primitive art of Tagore

Syed Ashraf Ali

Nothing can be both primitive and modern. But the paintings of a maestro have very surprisingly been classified as "Modern Primitive Art." What is more, very few on earth know this towering personality as a painter. He is adored and eulogised in every nook and corner of the world not as a "man of colours" but as a "man of letters" and a "man of sound." The name of Rabindranath Tagore indeed suggests primarily no theme connected with the history of art. All over the world is he acknowledged as a great poet, a great writer and a great musician. His success in everything he touched was so complete that it is hard to even say what his forte was. Very few among us, however, know that the versatile genius was not only a poet, a writer and a musician of the first order, but he also excelled in painting. He painted fast and with a sure hand, in between the intervals of his literary activity, finishing each picture at one sitting, and left behind nearly 2,500 paintings and drawings, all done during the last 13 years of his life -- a no mean achievement, considering that during the same period he also published more than 60 volumes of new literary writings, poetry and prose. The unique and astonishing creativity of Tagore "stemmed basically from the fact that he was a mystical, philosophical being -- in everything, he was constantly searching for some bearing on life, some balance and symmetry of vision." His life is the story of a great and passionate heart, which was entirely filled with two things: love and sorrow. Love, not in the sense of likings or preferences, or sympathy or aesthetic test, but in its deepest form, charity, a deep religious relationship to men and things. His life was an uninterrupted giving of himself, and his painting was yet another brilliant way of giving himself, which he discovered after many other attempts. He himself described his paintings as 'my versification in lines' and confessed in a letter that he was 'hopelessly entangled in the spells that the lines have cast all around me.' There is no doubt that many of these drawings are marked by a strong feeling for rhythm, but apart from this affinity there is little in common between the poetry and the painting of this great maestro. It was in 1928 that the versatile genius began his experiments in an entirely new and unforeseen medium of creative expression, namely, painting. He had always been drawn to this art and had occasionally cast furtive and longing glances at it; as a young boy he had seen elder and versatile brother Jyotindranath draw. His first attempts at drawing, however, came at the early age of nine when his and his brother's education was in the hand of private tutors. But to him drawing was then nothing thrilling, it was just included in a long list of subjects comprising geometry, arithmetic, science, history, geography, physiology, Sanskrit, Hindi, Bengali, anatomy and, of course, music. At 12, he had a more personal and less formal contact with drawing when he made little sketches during a tour of North India with his father. But drawing still did not quite capture his imagination in any way. At 30, drawing again made a re-appearance in his life, when he used to spend a few private hours, now and then, practising it. The sporadic sketches and drawings show an innocent hand. But Tagore obviously did not really like what came about, and this, combined with the fact that he did not apply himself with total dedication, saw an end to that particular tryst with painting, which he regretted. Thirty long years would pass before he wooed the world of visual expression. Later, when his nephews Abanindranath and Gyagendranath discovered their talents for painting he encouraged them in their pursuit and helped in founding what came to be known as the modern movement in Indian Art. He himself hardly ever took the brush in hand. But though he did not wield a brush, he doodled freely with his pen and the expression gushed forth like a flood; completely abstract forms conceived in a search for purely visual balance poured out of his pen. They would come mainly in the shape of "doodles" upon his manuscripts when he paused for thought while he wrote. The "doodles" appeared suddenly and with abundance in his manuscripts of 1923-24 and subsequent years. "The scratches and corrections in my manuscripts cause me annoyance," he wrote. "I want to make my corrections dance, connect them in a rhythmic relationship and transform accumulation into adornment." And the poet really let himself go. He had no training and no reputation at stake as a painter, and so he went on without inhibition, without affectation. He drew on whatever paper was at hand and with any instruments and colours, with the unfortunate result that the preservation of these paintings, many of which are of extraordinary quality, presents today a serious problem. He drew on whatever ideas he believed in, both modern and traditional, and tried to achieve a vision which instead of "rejecting all the forces at work, imbibed and sifted through them, and ultimately transcended them to acquire a progressive, personal vision of his own." In 1924, on his way to Argentina, Tagore wrote the Yatri and the Purabi. In Buenos Aires, he fell ill and while staying there, he dedicated his poems to his hostess Madame Victoria Ocampo. It was she who remarked on the striking texture of the adornment on the manuscripts and pointed out how visually appalling they were. The "doodles" radiated the feelings of a deeply sensitive artist, acutely aware of his milieu, all superbly conveyed through a technical excellence of the highest order. By 1928, Tagore abandoned the pretext of turning "accumulations on his manuscripts into adornments" and closed, self-contained monochromes in fountain pen ink began to appear on the blank spaces on his manuscripts. Soon after, he started drawing in two or three tones, and he used his figures or bits of rag to spread or blend them. But he hardly used any brush. In 1929, Tagore began to see his creations in terms of actual forms and figures, and a sudden plethora of those gushed forth, like reawakened visions from a subconscious memory, "very amialistic, hobgoblin-like faces, people and creatures" started appearing. He had already started using separate pieces of paper to paint on, using fast-sticking coloured inks, crayons, corrosive inks, vegetable colours and varnishes -- anything and everything that would quickly dry and stick, thereby preserving his original flash in spite of repeated assaults with the brush. He never bothered to care how long it would last. The paintings of the great poet are indeed extraordinary and provide us with a unique style of painting. In the words of the distinguished art-philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy, "An exhibition of drawings by Rabindranath Tagore is of particular interest because it puts before us, almost for the first time, genuine examples of Modern Primitive Art." When the pictures of Tagore were exhibited in Gallery Pigalle in Paris in 1930, it earned a world-wide reputation. The Comtesse de Noailles wrote: "The Pictures of Tagore which begin like the entry of the spirit into sleep by dreamy and vague spirals, define themselves in the course of their remarkable execution, and one is stupefied before this masterly creativeness which reveals itself, as much in the trifling as in the vast, why has Tagore, the great mystic, suddenly, without knowing, set at liberty that which in him scoffs, banters and perhaps despises." Tagore himself admitted, "My pictures represent no preconceived subject. Accidentally, some forms, of whose genealogy I am totally unaware, takes shape from the tip of my moving pen and stands out as an individual " The paintings of Tagore indeed are not only colourful and varied but those are literally "Pictures about himself -- much nearer to his music than to his poetry." The author is a former DG of Islamic Foundation, Bangladesh

|

|