Experiencing Kaiser Haq's poetry

(The following is an excerpt of a talk given at the book launching of Kaiser Haq's Published in the Streets of Dhaka on 17 February, 2007.)Abeer Hoque

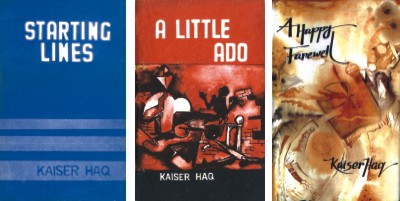

I'm here to tell you about my experience of Kaiser Haq's poetry. I am Bangladeshi but I grew up abroad. I was born in Nigeria, lived there for 13 years, and then moved to the States. My knowledge of Bengali literature was limited to a few Tagore poems (of course). Given the Western bent of Western education, things didn't change, even when I went for my MFA in writing. White Western writers, every which way you went, and given that I was in San Francisco, a few White Western gay writers, thrown in for good measure. It was a year into the program that I took my first poetry class. We learned various ways to analyse poems, break down their structure and intent. One of our last assignments was to pick a poem of our choice and analyse it given the tools we had learned in class. I decided to pick a Bangladeshi poet, although I knew none. So I asked my Bangladesh experts: Google, naturally, my Sabrina khala (a lover of literature), and my father (a scientist, and a writer himself). I was given Kaiser Haq's name, among others. I liked that we shared a similar last name though I had no expectations of liking anything else. You see, I liked very little poetry, even though I was a wannabe poet myself. My education had taught me to understand more poetry, to see what the author was trying to do, what was active between the lines, but it hadn't necessarily gotten me to like more of it. At the time, I was living in Berkeley, and it just so happens that UC Berkeley has the biggest and best library in the state of California. It also happens to have one copy of Kasier Haq's book, A Happy Farewell. I thought I would flick through the book and pick a poem I kind of liked that had a lot of prosodic elements I recognised. I'd write up my report, and that would be that. Instead, I devoured the entire book from front to back. And then proceeded to violate all the publisher's copyrights as well as my company's photocopy machine rules, by copying the entire book for myself. You see, I knew, at once, when I read the very first poem, that Kaiser Haq was speaking for me, he was speaking to me. His language, his subjects, his sardonic and suddenly sexy turn of phrases, it was all utterly modern and utterly captivating. And more than this, I was surprised that someone who had grown up so differently from me could describe things in a way that made so much sense to me. I disagree (with) Kaiser (when he says) that subcontinental poets writing in English might not have their fair share of rhythm and rhyme. Living on "the surface of language" as (he) quotes Cioran saying, rather than being rooted in it, can be another way to see the world, perhaps more elemental, perhaps even more eloquent, than others. This collected works we're here to celebrate, Published in the Streets of Dhaka, brings together some of Kaiser's old debut publications along with new poems. I found the newer poems to be richer in reference, but the same pleasurable cocktail of imagery and irony. One of my favourite writing teachers, Kate Brady, once told me that creating art was serious play. When I read Kaiser's poetry, I am ever struck by his sense of this: serious play. From Buddha to Bloomsday, from Sartre to Salgado, from Dhaka to Dublin, he weaves his history of the world in words that are alternately deep and light, fleet and bright. The poem I chose to analyse, five years ago in San Francisco, was called "Moon". Moon

Aunts in orgies of gossip Plough through mountains of betel, Outchewing a flock of goats; I don't listen to them. Self-immured, hands to the head, elbows on a creaking escritoire, I've missed dinner to imagine the real terrors behind rumours that bite their own tails; when suddenly the air is tinted silver, through the window a rain-washed garden looks in like eyes prettified by tears, on the river beyond a canoe goes by with a glitter: it's that ageless moron again, the moon. You don't belong here, I tell it sharply. Abeer Hoque is a writer and photographer, currently in Bangladesh on a Fulbright Scholarship.

|

|