Global warming and Bangladesh

Paying the price of others' sin?

Md Saidur Rahman

I hear the waves on our island shoreThey sound much louder than they did before A rising swell flecked with foam Threatens the existence of our island home. A strong wind blows in from a distant place The palm trees bend like never before Our crops are lost to the rising sea And water covers our humble floor. Our people are leaving for a distant shore And soon Tuvalu may be no more Holding on to the things they know are true Tuvalu my Tuvalu, I cry for you. [A Poem on "Tuvalu and Global Warming" written by Jane Resture] Not long ago, Tuvalu, a tiny archipelago of nine islands of only 10 square miles located halfway between Hawaii and Australia in the southwest Pacific Ocean and home to over 11,000 people, contained a number of beautiful islets, but it is sad to say that many of these are now going under water due to sea level rise -- the obvious consequence of global warming. The threat of sea level rise may bring complete disaster to the low-lying coral atolls within few decades. Warm water takes up more space than cold water does. This simple fact of physics, utterly inexorable, is one of the two or three most important pieces of information humans will have to grapple with in this century. And the people who get to grapple with it first are in places extremely vulnerable low-lying deltas like Bangladesh, where suddenly the high tides are intruding across its southern cost, eroding foundations and salt-poisoning crops. Other low-lying countries are also at risk, such as the Netherlands and tiny islands in the South Pacific that could eventually be swallowed by the expanding oceans. But the population of these countries is only a fraction of that of Bangladesh. A little increase in temperature, a little climate change, has a magnified impact here. That's what makes the population here so vulnerable. The global warming and consequent threat of sea level rise may bring disaster to the inhabitants of Bangladesh. The long-term threat from climate change and sea-level rise may make many parts of the country uninhabitable. The increasing intensity of tropical weather, the increase in ocean temperatures, and rising sea level -- all documented results of a warming atmosphere -- are making trouble for the region. Recent country-wide heavy rainfall and huge death tolls due to land sliding in Chittagong are prior signal of alarming catastrophe. Tropical storms have also long frightened the islanders. Bangladesh fears it will be crushed by storms, rising ocean levels and there will be disruptions to marine life caused by global climate change. Millions of people face the possibility of being among the first climate refugees, although they never use that term. Already a million people a year are displaced by loss of land along rivers, and indications are increasing. The one meter sea level rise generally predicted if no action is taken about global warming, will inundate more than 15 percent of Bangladesh, displacing more than 13 million people and cutting down the crucial rice crop production. Intruding water will damage the Sundarbans mangrove forest, a world heritage site. Consequences

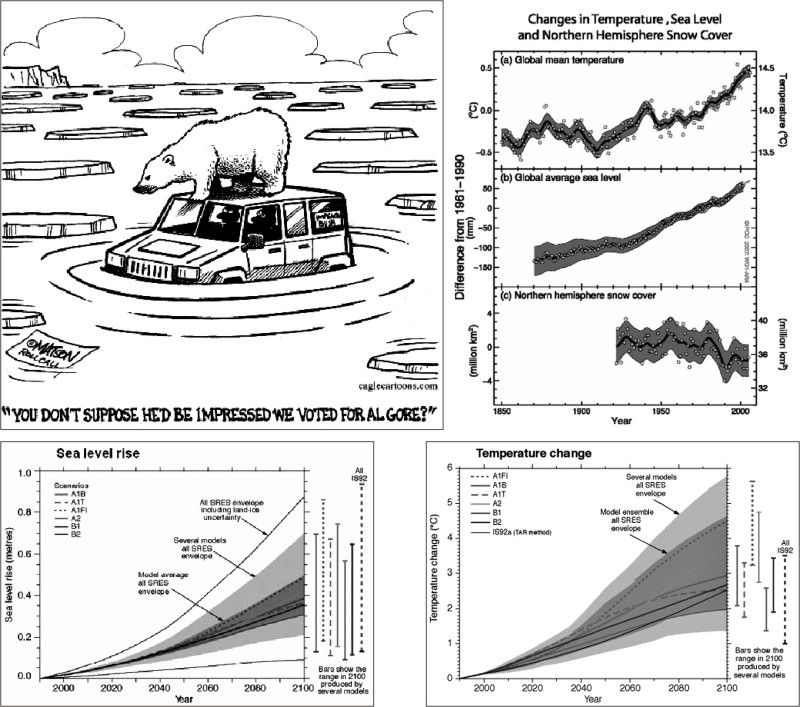

Global warming is invisible. Just as a frog in a slowly warming frying pan cannot sense his impending doom, so, are humans unaware of the disaster that is descending upon them. Global warming is the increase in the average temperature of the Earth's near-surface air and oceans in recent decades and its projected continuation. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded in Paris, on February 2nd, 2007 that warming of the climate system is unequivocal. Global mean surface temperature has increased by 0.74 ± 0.18 °C (1.3 ± 0.32 °F) over the last 100 years likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations, which leads to warming of the surface and lower atmosphere by increasing the greenhouse effect. Natural phenomena such as solar variation combined with volcanoes have probably had a small warming effect from pre-industrial times to 1950, but a small cooling effect since 1950. An increase in global temperatures can in turn cause severe environmental changes, including sea level rise, and changes in the amount and pattern of precipitation as well as fluctuations in weather patterns never seen before. There may also be increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, though it is difficult to connect specific events to global warming. Other effects may include changes in agricultural yields, glacier retreat, reduced summer streamflows, species extinction and increase in the ranges of disease vectors. Farmlands may experience droughts, while deserts could become vast stretches of oases. Food crop reduction is a possibility and the salination of groundwater is very likely. Vicious storms will become more frequent and hot climates could see a drastic rise in their mean temperatures. Ice caps will melt, entire countries will report much unpredicted weather patterns, and many islands as well as coastal low land deltas like Bangladesh may totally or partially disappear. Sea level rise can be a product of global warming through two main processes: expansion of sea water as the oceans warm, and melting of ice over land. Sea level has risen around 130 metres (400 feet) since the peak of the last ice age about 18,000 years ago. Most of the rise occurred before 6,000 years ago. From 3,000 years ago to the start of the 19th century sea level was almost constant, rising at 0.1 to 0.2 mm/yr. Observations since 1961 show that the average temperature of the global ocean has increased to depths of at least 3000 m and that the ocean has been absorbing more than 80 percent of the heat added to the climate system. Such warming causes seawater to expand, contributing to sea level rise. Mountain glaciers and snow cover have declined on average in both hemispheres. Widespread decreases in glaciers and ice caps have contributed to sea level rise. Global average sea level rose at an average rate of 1.8 (1.3 to 2.3) mm per year over 1961 to 2003. The rate was faster over 1993 to 2003, about 3.1 (2.4 to 3.8) mm per year. Whether the faster rate for 1993 to 2003 reflects decadal variability or an increase in the longer-term trend is unclear. There is high confidence that the rate of observed sea level rise increased from the 19th to the 20th century. The total 20th century rise is estimated to be 0.17 (0.12 to 0.22) m. Global warming is predicted to cause significant rises in sea level over the course of the twenty-first century. Scientists constructed thirty-five scenarios to explain the intricacies and possibilities involved in the many factors affecting global average sea level changes. Taking all 35 SRES scenarios into consideration, the scientists projected a sea level rise of 9 cm to 88 cm for 1990 to 2100, with a central value of 48 cm. The central value gives an average rate of 2.2 to 4.4 times the rate over the 20th century. It can be expected that by 2100 many regions currently experiencing relative sea level fall will instead have a rising relative sea level. Extreme high water levels will occur with increasing frequency as a result of mean sea level rise. Their frequency may be further increased if storms become more frequent or severe as a result of climate change. Before the end of this century, (without particular emission reduction policies) global temperature is likely to increase by 1.1 to 2.9°C (2 to 5.2°F) if we follow the emission scenario B1, or 2.4 to 6.4°C (4.3 to 11.5°F) if we follow the fossil intensive scenario A1FI. Thus, a total range of 1.1 to 6.4°C (2 to 11.5°F). The corresponding range for sea level increase is 18 to 59 cm (7 to 23 inches), but that is an underestimate because it does not take into account certain glacial processes. In the long term (centuries), the Greenland ice sheet might contribute up to 7 meters (23 feet) to sea level, and this without the contribution from Antarctica. Heavy precipitation events are likely to increase (with the accompanying risks of floods). Heat waves such as the one which killed between 40 and 70 thousand persons in Europe in 2003 are very likely to become more frequent. Intense tropical cyclone activity is likely to increase. A mean annual warming of 2 degrees Celsius or higher by the 2050s and 3 degrees Celsius for the 2080s is projected. Modest declines in annual precipitation in the Pacific Ocean region are also expected along with heavier rainfall intensity. Given emissions of greenhouse gases up to 1995, a 5.12 cm rise in sea-level is inevitable. However, even if all countries met their Kyoto Protocol commitments, and if all emissions of greenhouse gases ceased after 2020, a sea-level rise of 14-32 cm is very likely. Carbon dioxide is the most important anthropogenic greenhouse gas. The global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has increased from a pre-industrial value of about 280 ppm to 379 ppm in 2005. The present atmospheric concentration of CO2 is about 383 parts per million (ppm) by volume. Future CO2 levels are expected to rise due to ongoing burning of fossil fuels and land-use change. The IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios gives a wide range of future CO2 scenarios, ranging from 541 to 970 ppm by the year 2100. Fossil fuel reserves are sufficient to reach this level and continue emissions past 2100, if coal, tar sands or methane clathrates are extensively used. - Continued greenhouse gas emissions at or above current rates would cause further warming and induce many changes in the global climate system during the 21st century that would very likely be larger than those observed during the 20th century. For the next two decades, a warming of about 0.2°C per decade is projected for a range of SRES emission scenarios. According to a recent report of IPCC, on an average global average surface air temperature will increase from 1.8°C to 4.0°C while sea level will increase by 18 cm to 59 cm by the end of the 21st century. If it happens, some of the projected impacts include:

- By mid-century, annual average river runoff and water availability are projected to increase by 10-40 percent at high latitudes and in some wet tropical areas, and decrease by 10- 30 percent over some dry regions at mid-latitudes and in the dry tropics, some of which are presently water stressed areas. Heavy precipitation events, which are very likely to increase in frequency, will augment flood risk. Drought affected areas will likely increase in extent. In Africa alone, by 2020, between 75 and 250 million people are projected to be exposed to an increase of water stress due to climate change. Water security problems are also projected to intensify by 2030 in southern and eastern Australia.

- Glacier melting in the Himalayas is projected to increase flooding, rock avalanches from destabilised slopes, and affect water resources within the next two to three decades. This will be followed by decreased river flows as the glaciers recede. Climate change is projected to impinge on sustainable development of most developing countries of Asia as it compounds the pressures on natural resources and the environment associated with rapid urbanisation, industrialisation, and economic development.

- In the course of the century, supplies of water stored in glaciers and snow cover are projected to decline, reducing water availability in regions supplied by meltwater from major mountain ranges (such as the Himalayas in Asia or the Andes in Latin America). In North America, the decreased snowpack in western mountains is projected to cause more winter flooding, and reduced summer flows, exacerbating competition for over-allocated water resources.

- Freshwater availability in Central, South, East and Southeast Asia, particularly in large river basins, is projected to decrease due to climate change, which could, in combination with other factors adversely affect more than a billion people by the 2050s.

- In Southern Europe, climate change is projected to worsen extreme heat and drought in a region already vulnerable to climate variability, reducing water supplies, hydropower potential, summer tourism, and crop productivity.

- Coasts are projected to be exposed to increasing risks, including coastal erosion, due to climate change and sea-level rise. Many million more people are projected to be flooded every year due to sea-level rise by the 2080s. The numbers affected will be largest in the megadeltas of Asia and Africa while small islands are especially vulnerable. Coastal areas, especially heavily-populated mega-delta regions in South, East and Southeast Asia, will be at greatest risk due to increased flooding from the sea and in some mega-deltas flooding from the rivers.

- Corals are threatened with increased bleaching and mortality due to rising sea surface temperatures. Coastal wetland ecosystems, such as salt marshes and mangroves, are especially threatened where they are sediment-starved or constrained on their landward margin. Degradation of coastal ecosystems, especially wetlands and coral reefs, has serious implications for the well-being of societies dependent on the coastal ecosystems for goods and services.

After the 21st century, very large sea-level rises (estimated to 4-6 meters or more, that is 13 to 20 feet or more) that would result from widespread deglaciation of Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets imply major changes in coastlines and ecosystems, and inundation of low-lying areas, with greatest effects in river deltas. Relocating populations, economic activity, and infrastructure would be costly and challenging. Impacts of climate change will vary regionally but are very likely to impose net annual costs which will increase over time as global temperatures increase. In general, the net annual costs of the impacts of climate change are projected to increase over time as global temperatures increase. For example, while developing countries are expected to experience larger percentage losses, global mean losses due to climate change could be 1 to 5 percent GDP for 4°C (7°F) of warming. Threat to Bangladesh

Bangladesh is most vulnerable to several natural disasters and every year natural calamities upset people's lives in some parts of the country. The tropical location and geographical setting of Bangladesh makes the country vulnerable to natural disasters. The mountains and hills bordering almost three-fourths of the country, along with the funnel shaped Bay of Bengal in the south, have made the country a meeting place of life-giving monsoon rains, but also subjected it to the catastrophic ravages of natural disasters. Its physiography and river morphology where the mighty Brahmaputra, Ganges, Meghna and many rivers criss-cross to form a vast delta of alluvial plains that are barely above the sea level, making it prone to flooding from waterways swollen by rain, snowmelt from the Himalayas, and increased infiltration by the ocean, largely contribute to recurring disasters. A combination of geography and demography puts it among the countries that specialists predict will be hardest hit as the earth heats up although its own carbon footprint is small. The root cause of most of its global warming problems lies in the heavily industrialised world. Yet, as sea levels rise only a little Bangladesh will pay a heavy price. Bangladesh, a densely crowded and developing small nation, contributes only a minuscule amount to the greenhouse gases slowly smothering the planet. But the projected climate change is likely to affect its millions of already vulnerable people. Nearly 150 million people, the equivalent of about half the US population, live packed in an area slightly smaller than the American State of Iowa and over 15 million of them are concentrated into the overcrowded capital city of Dhaka. Many of them have abandoned their homes in the countryside relocating to Dhaka to seek an elusive better life. Most are not successful in their quest for improved living standards and a brighter future and live in low lying parts of the city subject to flooding and diseases. All of Dhaka and most of Bangladesh lies within a mostly flat alluvial plain and many areas are just a few feet above sea level. Violent storms regularly sweep in from the Bay of Bengal to wreck havoc upon the land and inhabitants. Warmer weather and rising oceans are sending seawater surging up Bangladesh's rivers in greater volume and frequency than ever before, specialists say, overflowing and seeping into the soil and the water supplies of thousands of people. Heat waves, floods, storms, cyclones, land-sliding, fires and droughts cause increased deaths and harm to lives and properties. On an average, river erosion takes away about 19,000 acres of land and more than one million people are directly or indirectly affected by river-bank erosion every year in Bangladesh. Million of people are projected to be at risk from coastal flooding due to sea level rises. As a low lying tropical country Bangladesh is on the front line of the consequences of global warming. Already the storms are becoming more violent. Recent heavy rainfall and many deaths in Chittagong due to land sliding are also prior notice for alarming future. People along the shoreline have noticed a rise in the sea level. Many have already been forced to move several times to higher ground. The planting of crops has been affected. Most crops do not fare well as salt water moves into the water table. World Bank reported in 2001 sea level rising about 3 mm/year in the Bay of Bengal. It warned of loss of Bengal tigers in the Sundarbans, world's largest mangrove heritage, and threats to hundreds of its flora and fauna. The one meter sea level rise will inundate 15 to 20 percent of Bangladesh. This means predicted sea level rise, at a rate that is increasing, will not only affect millions of people -- estimates are 13 to 30 million -- but will also flood out much rice production. The World Bank warned of a decline of rice crop up to 30 percent with predicted sea level rise. If there is an increase in temperature of 6 °C, the maximum predicted by the IPCC, then the greater flow of water through Bangladesh's three great rivers will inevitably lead to between 20 and 40 per cent more flooding. On the southern coast, erosion driven in part by accelerating glacier melt and unusually intense rains will cause relentless sufferings to millions of people. In the dry northwest of the country, droughts are getting more severe. If the sea rises by a foot, which some researchers say could happen by 2040, the resulting damage would set back Bangladesh's progress by 30 years and up to 12 percent of the population would be made homeless. And if sea level rises by 3 feet by the turn of the century, as some scientists predict, a fifth of the country will disappear. As many as 30 million people would become refugees in their own land, many of them subsistence farmers with nothing to subsist on any longer. It will result in more density of population. If it happens, tomorrow's poverty will be far worse than today's. Bangladesh does not have preparations for the fallout of global warming as well as any capacity or planning to go through a real challenge under climate change, biodiversity, and desertification. Conclusions

For at least 200 years, two dynamics have driven the global economy. One is the enormous growth of material wealth underwritten by humankind's rampant exploitation of fossil fuel. The other is the relentless widening of the gap between the rich and the poor. Now, everyone agrees that the rich/poor divide fuels conflict. Since World War II, industrial nations have pumped an increasing amount of CO2 into the atmosphere every year. Many scientists believe this buildup of CO2 is why the 1990 was the hottest decade ever recorded. This warming also affects climate, and may be the reason for a surge of tornados in the U.S., landslides in Italy, droughts in Africa, and flooding in Asia and Australia. The planet has seen climate shifts before -- ice ages and warming trends -- but nature was never this fast. This climate change, say many scientists, is likely the work of man and it could cause hunger for millions with a sharp fall in crop yields. So, how will the world cope with multi millions of poor homeless people migrating to who knows where? Who will take the starving hordes in? Who will house them, who will feed them, who will provide medical care, who will see to their welfare? Will it be the industrialised nations like the US, the largest polluter in the world that contributes about 25 percent of greenhouse gas emissions with a population lesser than 5 percent of the world's total? Climate change is undeniably the most urgent problem facing the world today. Scientists who do take global warming seriously are becoming more concerned that global warming is taking place at a faster pace than first projected. They also are convinced that no matter how hard the nations of the world try to stop and to reverse the process it is already too late. Politicians and world's leaders who had previously dismissed global warming as a far-off problem are starting to see it as a clear and present danger, although US government, has done virtually nothing, even has not signed the Kyoto Protocol till now, despite the fact that US is the world's largest contributor of greenhouse gases.. The world will face some unpleasant consequences from greenhouse gas emissions largely caused by human activity no matter what collective actions are now taken. We humans and the animals and vegetation of our planet will pay a dear price for our often careless rush into the massive burning of fossil fuels. We have only one earth -- care and share it. Md Saidur Rahman is a government official working with Bangladesh Railway, presently under deputation pursuing higher studies in Environmental Policy at Hiroshima University, Japan.

|

|