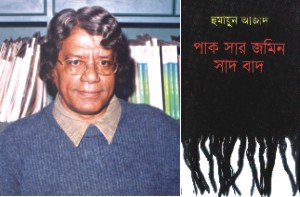

On Humayun Azad and Pak Saar Zameen Shad Bad

Farook Chowdhury

Till the establishment of the caretaker government in January of this year, with violence and political chaos on the rise, Ekushey February was coming under attack from the seemingly growing Islamic religious resurgence in the country. Last year, like all the others, thousands of barefoot people wearing black badges singing "Amar bhaiyer rakte rangano Ekushey February, ami ki bhulite pari," walked at dawn to the Shaheed Minar to lay wreaths of marigold and krishnachura bouquets. The speakers at the Shaheed Minar played recitations from the Qur'an instead of the customary songs, poetry reading and speeches. When asked about this change, the Dhaka university authorities in charge of coordinating the program brushed the question aside. They said the Quranic recitation was played only for a minute and that too to test the speakers, which previously would have been done unnoticed with a "hello". The recitation was actually played intermittently for a full night, morning, and noon. Around the country, in several towns and smaller communities, concerts and theaters could not be held, either because they were stopped, or for fear of attack.On a Friday night in late February 2004 when Humayun Azad left the Ekushey boi mela and was walking towards the Atomic Energy Center, several men attacked him with butcher knives. They stabbed him at the back of his head, twice in the left side of his face and once in the shoulder, leaving him bleeding profusely. The assailants were never caught. Over the past years he had received death threats, not exactly fatwas. Since his book Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad came out those threats to his life became more real. Largely allegorical, with indefatigable exploring of the verbal and carnal, the language of Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad is a phantasmagorical indictment of the national consciousness of Bangalees. Its portrait of power-cum-violence is unforgiving and merciless, and the language is charged with anger and abuse. It uses the rise of Muslim religiosity in Bangladesh society as a point of departure, but moves beyond it, interconnecting authority with power, power with wealth, wealth with humiliation. In the horrible world of Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad there is no place for compassion. Like Pasolini's Salo, it creates victims with their faces emerging powerless in front of fascism, and the powerful - a group of cheats and conmen at the service of faith and belief -- gloriously feasting on success and optimism. Girls are raped and savored, as sacrifices for total-kill, as revenge, and to satisfy the carnal desires of Jihadists pledged to free Bangladesh from the hands of blasphemous Hindus and Jews. Humayun Azad was born in a village named Rari Khal in Munshiganj on April 28, a few months before India wrested independence from the British and was split into the two countries of Pakistan and India. Humayun Azad, a linguist by profession, wrote poems, novels and essays, none of which have been translated from Bangla. A social liberal, steeped in the teachings of Rabindranath Tagore, Michael Madhusudhan, Bankim Chandra Chatterji, to name a few, his contributions to Bangla linguistics, literature and language are considerable. His devotion to Bangla was immeasurable. "I could have lived abroad, but did not," he said, "not because of the country, but because of the language; I live inside Bangla language." After Bangladesh came into being, there were great expectations that at last Bangla would flourish, that, Ekushe February, our 'unofficial' independence day, would inspire a new phase in the development of Bangla. It would become one of Azad's principal concerns to speak out against the increasing vulgarization of Bangla, a process he grieved was coming about due to the use of poor, ungrammatical and vulgar Bangla by the ruling classes, particularly politicians, as well as because of widespread use of English. The language of Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad is deliberately vulgar, and when the Jihadist narrator and his lover Kanaklata metamorphose in the final act of the novel to hold the torch of love, the vulgarity ends and we are thrown inside the language of Tagore. On a more apprehensive note, Humayun Azad traces the failure of state building in his book-length essay Is this the Bangladesh we wished for? -- a treatise more Lacanian than postmodern structural. Disappointed, sad and angered, he apprehends that mediocre and petty-minded politicians, industrialists, civil servants, intellectuals, all who have gained prominence and risen to positions of authority, are contributing to push the country into dark ages. Dedicating the book to a poem Humayun Azad warns us to take his emotions, hyperbole, bluntness, and most of all, anger, seriously: I beg of you do not ever hurt me by speaking of Bangladesh Do not wish to know about the spoilt, rotten 55,000 square miles; its politics, Economics, religion, sins, deceits, innumerable humans, living, murder, rape, Do not hurt me by asking me about the blind journey towards medieval times; I cannot stand it, not for a moment - there are reasons for it. 'There are reasons'- and primarily Humayun Azad is interested in reflecting on how fantastic, gargantuan opportunities to establish a modern, freedom-loving, rationally- spirited, democratic society went astray. In the decades after the independence of Bangladesh, the country spiralled into a cycle of political treachery, suspicion and murder. Over the last five years stories of murders, rapes, bomb and grenade attacks were routinely published in the daily newspapers. Indeed, in a sort of fait accompli acknowledgment people continued to complacently live their daily lives, while denial had become common among heavier quarters. Top political leaders, now being rounded up, denied the violence and called it media-propaganda, a non-localized, global phenomenon (Madrid, Bombay, Bali, USA). Even a former prime minister, in one of her parliamentary speeches, praised the Islamic groups for their significant contribution to the stability of the country, when those same groups had taken the country hostage to their bloodshed. Humayun Azad waged a war in words against the spirit he understood thwarted growth, choked spontaneity and killed the will of the liberation war that brought independence. He was outspoken and spared no one, and in a repressed hierarchical society such as Bangladesh, his daring attracted attention of the wrong kind. In Bangladesh, sexual expression is a social prohibition, as it is a moral violation; it does not stunt sexuality, but finds nasty, secret and dirty ways of fulfillment. Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad does not, however, explore sexuality. It depicts repressed sexuality expressing itself in a violent way--as rape--by forcing the weak to submit to an authoritarian rule. This metaphor of rape is taken to new, stunning heights, and the use of explicit language could be difficult reading for most Bangalees. The middle-class, the so-called liberated mind, shrinks from it with embarrassment, while the religiously initiated are inflamed by its blasphemy and finds the language and the book impossible to tolerate. Humayun Azad evokes extreme language to talk about extremes in Bangladeshi society, where young males and females are unsafe and are a victim of, he laments, a society of licentious, power-hungry, ill-educated people bent on taking the country back to the Dark Ages. His intention was to shock the readers into facing harsh realities, and not to hide from them. He was not concerned if anybody was going to be hurt or embarrassed by novel: "According to Mohammed Hafizuddin the best of the best are the young boys. He loves them - nine to ten years old ones; trains them little by little, and he buys different kinds of creams from Dhaka." Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad is provocative; it taunts readers with its outspokenness. The language of fornication is deliberately placed in opposition to tenderness, respect, humility and joy. Social prohibitions placed on women-- their movements, expressiveness, undulations, above all, their drive to life--make of rich sexuality a barren, dried-out river. Age-old customs, rituals and rules have put women behind walls, and in his book I prefer to call For Women Humayun Azad traces the history of this subjugation, structured and maintained through the institutions of marriage, image, laws and patriarchal control over the other sex. Bangalee customs and rituals of social festivities are devoid of joy, sexuality, merriment and wantonness. The shackles on women and sterile religious observances prevent the river of life from overflowing the land with dance, music, intoxication and necessary forgetfulness. In an antiquated and backward-looking society the increasing religiosity of Bangladeshis is gagging and putting a lid on those elements that could provide opportunities for growth, at overcoming old customs by creating a new national culture of abundance. Humayun Azad was alarmed at how the spread of religion was taking Bangalees along an irresistible path of darkness and fettered life, particularly for women. Dhaka, the capital city, mirrors all that is Bangladesh. Established around fifteenth century, Dhaka showed momentary glory and potential to be a great city in an otherwise long history of neglect, abandonment, and inability of its inhabitants to crown it, to adorn it with richness of life and culture. That opportunity finally came in December 1971, as the independent city of the Bangalees. Opportunities lost and squandered, after 36 years, the city now is a variegated place of rich and poor, sudden islands of luxury in the shape of glass-domed atriums within a sea of dilapidated, uncared-for buildings and slum areas, its streets crammed with every possible means of transport from pedal chains to 500 hp SUVs creating chaos and unbearable congestions, violence perpetrated by thugs, political groups and businessmen grabbing land, occupying streets, undertaking mindless, hazardous constructions anywhere and everywhere for shopping complexes, condominiums, restaurants, industries, offices; Dhaka is dangerously reaching a point of no return. The city is rude to its inhabitants and intrudes on their privacy with loud calls of modernity and religion; it fails to provide basic facilities of good water, uninterrupted power, entertainment, or even simple walking space. To the outside, Dhaka is a myth. It is where jobs are, money is to be made, flabbergasting the uninitiated, as they, the outsiders, flock into its heart in uncountable numbers, only to become a victim of its ferocious unwelcoming. With typical uncompromising, harsh, pointed words Humayun Azad writes: Your future you think is dancing in the streets of Dhaka Your dreams you think are floating in the skies of Dhaka Your life you think is resounding in the minarets of Dhaka Hell too you is heaven Fire to you is light Illusion to you is mystery Little do you know Dhaka is now fiercer than hell Little do you know Dhaka is now worse than cancer Dhaka now is a city of 401,800 rouges Dhaka now is a city of 308,000 lechers Dhaka now is a city of 504,300 deceits Dhaka now is a city of 202,000 harlots Dhaka now is a city of 1,045,300 frauds Dhaka now cannot offer you anything at all In Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad, the destruction, pillage, killing, murder, plundering, money laundering, chaos, lies and deceit all end with a Rising -- with the darkness of night giving way to a new dawn. Throwing his weapons, whiskey bottles, 'Pak Sar Zameen Shad Bad' cassettes in the river, the protagonist asks his lover, Kanaklata, to discard her veil and throw it into the waters. Over a bridge, they - the lovers - cross the river, into green fields, oak trees, bamboo forests, leaving hell behind, into a new journey, with innocence, with hope, entering a fresh beginning of childhood smelling of Mother soil, her dew, her cotton, her henna, her vermilion, their Golden Bengal - the early morning sun gloriously rising above the sea waters, where they stop to embrace in an eternal bond. In a stunning metaphor Kanaklata says, "Say Bismillah and put this vermilion straight from my forehead all the way into the partings of my hair". An incessant social and literary critic, Humayun Azad refrains from providing any political solution - any solution in fact - to overcome the misery befalling the country. His reflections take him into a journey where redemption, if there is one, can come about by overcoming all stigma, particularly religious stigma and morals, by holding to one's pride, love, tolerance and reverence. Humayun Azad survived the knifing, but died a year later in an apartment in Germany. The death remains a mystery, but most accounts hold it to be a natural death, perhaps due to complications suffered from the stabbing on his neck and face. Humayun Azad, however, lived untimely, in his dreams, where he saw humans, including Bangalees living a life of supreme will. I learnt to stand like others I learnt to walk like others I learnt to dress like others I learnt to keep my hair like others I learnt to talk like others They taught me to stand like them They commanded me to walk like them They ordered me to dress like them They made me to keep my hair like them They stuffed my mouth with their defiled words They made me live like them I lived in the time of the others. I did not see what my eyes wanted to look My time has not come I did not walk on the path my feet moved My time has not come I could not give the offerings my heart longed My time has not come I did not hear the song my ears wanted to hear My time has not come I did not touch what my skin wished My time has not come I did not find the world I looked My time has not come. My time has not come. I lived in the time of the others. Farook Chowdhury works for an international organization in Dhaka.

|

|