Feature

Near Heritage : Near Roots

Architecture of Uttar Banga

Students of Architecture Dept.

Some might go to China in search of knowledge. A group of 35 senior students accompanied by their members of the faculty from the Department of Architecture at the North South University in Dhaka did not have to go further than Bogra in North Bengal to learn from a repertoire of ancient archeological relics and architectural heritage, vernacular architecture and contemporary works of foreign architects and local masters. Bangladesh has some of the richest architectural heritage sites in the world. Bogra in the middle of North Bengal is possibly one of the richest sites. Some might go to China in search of knowledge. A group of 35 senior students accompanied by their members of the faculty from the Department of Architecture at the North South University in Dhaka did not have to go further than Bogra in North Bengal to learn from a repertoire of ancient archeological relics and architectural heritage, vernacular architecture and contemporary works of foreign architects and local masters. Bangladesh has some of the richest architectural heritage sites in the world. Bogra in the middle of North Bengal is possibly one of the richest sites.

They visited the archeological remains of Mahasthan Garh dating back to the second century BC. The students were impressed at the ruins on Nagri river that speak aloud of the society and culture of the past. In Sompura Vihara in Paharpur near Joypurhat, the students marveled at the largest Buddhist Monastery south of the Himalayas that expressed the high order of architecture that existed in the area in the 6-7C AD.

The group went to see the works of architect Muzharul Islam at the Limestone Project Housing (now split between the Joypurhat Girls' Cadet College and some army installations) and also at the Bogra Polytechnic Institute (done along with the famous American architect Stanley Tigerman). Their exposure to these works has given them a sense of modern architecture and its future direction in Bangladesh.

Finally on their way back they stopped at Sherpur, a small town known for its link with Shershah and several Mughal edifices.

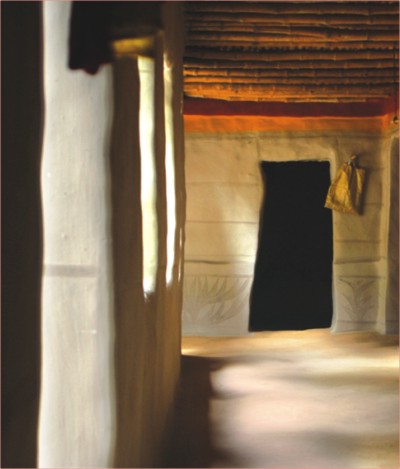

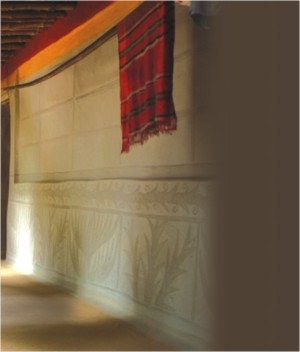

There they saw among others the beautiful Kherua mosque in early Mughal style. Without doubt the most illuminating for the students however was the visit to Eruilbazaar that allowed them to see, learn and document the timeless way of building mud houses in this part of Bangladesh.

The students brought back from this visit a wholesome experience of the architectural heritage, and the wisdom of the past in evolving man's built environment and as well as modern concepts of form making and spatial articulation. What follows is a memoir of the tour by Nabil Shahidi- a fourth year student who is an avid The students brought back from this visit a wholesome experience of the architectural heritage, and the wisdom of the past in evolving man's built environment and as well as modern concepts of form making and spatial articulation. What follows is a memoir of the tour by Nabil Shahidi- a fourth year student who is an avid

photographer as well.

This winter one of our faculties at the North South Architecture School asked us to go to Bogra. Why Bogra? He really enticed us to go saying Bogra has everything, starting from archaeological relics to modern architecture by master architects, vernacular architecture and many unique structures that we couldn't see elsewhere. For example, a Jain temple in classical south Indian style, a Library building again in Hellenistic classical order! A park with a revolving stage!! It all sounded so exotic. Within two days we organized a trip to Bogra, around 40 people were there. I now consider myself lucky as I had the chance to be part of this fantastic three day trip.

It was a mystic night, one day after the Christmas; mystic because it was so foggy we couldn't see even a yard ahead, especially after the Jamuna bridge. On the bridge we could only see the series of halogen lamps; couldn't even open the windows to hear the ripples because of the chill. Then onward it was only occasional headlights, and shouts by the bus helper now and then cautioning the driver of whatever was ahead that he was likely to miss. We were really thrilled and everyone on the bus were standing on their toes.

But arriving late at night in a hostel at the outskirts of the city, our faculty spared us less than two hours of sleep, dragging everybody from beneath the warmth of quilt, back in the bus again, and off to Mahasthan Garh at 5.30 in the morning. When we left the historic site several hours later around mid-noon, the fog had just started to disappear. In Mahasthan, we walked over and along the citadel walls of this fortified city of yesteryears, quarters of Bairagir Vita, and for moments went back in history to visualize how the people, their spaces, and the rulers were then. We saw the elements of urban design, brick work, and frustratingly how the bricks were plundered by the locals to build their own houses. I guess the Archaeology Department was not doing their job properly!

The next stop, without thinking about lunch, was the 7th Century Sompura Mahavihara, more popularly known as Paharpur, and the adjoining Satya Peerer Vita.

It was incredible how nearly a one and half millennium back our people could build such a huge edifice; no wonder it was included in the World Heritage list. The sheer scale of the monastery overwhelmed us. We were barred from climbing to the terraces on the seven storey high structure. But we went around, saw the structural system, and planning, came across a bunch of Japanese tourists with whom one of our Japanese speaking faculty had a brief chat, and were hurt to see that all the ancient terracotta plaques were being replaced by poor imitations done by the local potters and the salinity problem creeping in for decades. That raised a question nobody could answer- where were the originals going? It was incredible how nearly a one and half millennium back our people could build such a huge edifice; no wonder it was included in the World Heritage list. The sheer scale of the monastery overwhelmed us. We were barred from climbing to the terraces on the seven storey high structure. But we went around, saw the structural system, and planning, came across a bunch of Japanese tourists with whom one of our Japanese speaking faculty had a brief chat, and were hurt to see that all the ancient terracotta plaques were being replaced by poor imitations done by the local potters and the salinity problem creeping in for decades. That raised a question nobody could answer- where were the originals going?

In fact we observed that many of the display panels, especially in the Mahasthan museum, were barren, which looked really odd. On our enquiry we learnt that these were taken away to be sent to Musee de Guimet in Paris. Two of our faculties were in fact involved with the protests that were going on against their sending without following proper procedure. And to our delight we heard that very evening that the thieves were caught, while we were all sitting near Satmatha near a warm fire to have parota and kebab after the day's grueling travel, which had kept all of us without food the whole day. Satmatha is a really lively and busy city node, the centre point of Bogra, where seven axis roads mainly from the peripheral bypass road come and meet. If you know this morphology, the city will be legible to you as your palmtop, our faculty professed. In fact while teaching at BUET he brought a group of 65 BUET students in 1994 to stay there for 10 days in the very place we were staying, visit every place that we were going to and study the city up and down.

The day we were leaving, we stopped at the historic small town of Sherpur. Just behind the façade lining the highway lay vast expanses of green, and in the middle stood a beautiful burnt clay mosque, so humble yet ornately decorated, so simple and friendly yet majestic, tiny yet possessing an imposing grace that took us aback. It was nearly six century's old Khandaker Tola Masjid in Kherua, built in purely brick of various sizes and shapes, all the delicate details and intricate decorations were judiciously done which was incredible. We found one of the basalt inscriptions on the facade missing, which we later came to read was in the Karachi museum; it described how a pigeon brought the message to a Sufi Saint to have this mosque built.

Our trip was not all about going back in history. We in fact also went to the three very best examples of modern architecture in this country, and coincidentally all three were in exposed brick. However, the oldest one in Joypurhat by the first architect of Bangladesh Muzharul Islam was covered up with plaster by their new owners. The series of four storied row houses in one directional parallel walls integrated the very basics of architectural language, even the elaborate cover up could not conceal the relationship between void and mass, which we understood better when visiting another masterpiece by the same architect in the town- the Polytechnic Institute. The quality of space was fantastically manipulated to say the least. Unfortunately here too little maintenance is pushing the structures to go into oblivion and lose some of their charms.

On second day when we arrived at the SOS Children's Village, the sun was just setting behind the silhouette of Vimer Jungle in the horizon. It was a small complex on a slightly undulating terrain, which the architect quite competently handled by designing few split level cottages around a court. It was designed by the pioneer new genre architect Raziul Ahsan, who tragically died in a road crash; incidentally the day was the tenth anniversary of his sad departure. Under the fading sun, the complex in red brick and pitch roof looked homely. Yet we were not let in as the Director was away for Hajj, and the Bua in charge was not sure. However, the disappointment was partly compensated as we could just rush in to Gokul Medth (Lokkhindorer basor ghar) before dusk, before closing down for the day. On second day when we arrived at the SOS Children's Village, the sun was just setting behind the silhouette of Vimer Jungle in the horizon. It was a small complex on a slightly undulating terrain, which the architect quite competently handled by designing few split level cottages around a court. It was designed by the pioneer new genre architect Raziul Ahsan, who tragically died in a road crash; incidentally the day was the tenth anniversary of his sad departure. Under the fading sun, the complex in red brick and pitch roof looked homely. Yet we were not let in as the Director was away for Hajj, and the Bua in charge was not sure. However, the disappointment was partly compensated as we could just rush in to Gokul Medth (Lokkhindorer basor ghar) before dusk, before closing down for the day.

Yet what impressed us all beyond description was an entire village of 1-2 storied mud houses, just 10-km off the beaten track, which none of us were prepared for. In fact there was a little reluctance and a negative apprehension on our behalf to go to a village

which nobody had heard about before, and possibly spoil half a day. If I hadn't visited this unknown place called Eruilbazaar that day, my life would have remained unfulfilled. That vernacular architecture could be so beautiful, we wouldn't have ever known if we missed this trip.

It was colourful, colour made with natural soil from different parts of earth, river bank (red), paddy field (yellow), bed of the pond (black). These were ornately decorated with different geometric and floral patterns, a style developed by the housewives and small children who would really enjoy making all these wall decorations with their fingertips. This was carried over all the opening, the door and window leaves, all had symmetric floral designs done in bright colors. Windows were of moderate size and deep, with bamboo lintels. The thick walls were tapering, starting half a yard from below ground. The mud was mixed with paddy roots and cut hays, prepared by stamping thoroughly, and applied to build walls in phases.

Unlike in other parts of the country, these were not hut type, but a series of rooms around courtyards, the rectangle was completed by encircling walls on the side where rooms were missing. These were compact, densely built, with facilities like cow shed and kitchen leaned against mud walls. Houses were entered through gates, often below an upper floor room. Floors were of mud too laid over split palm logs or bamboo, which often protruded outside through the wall creating a kind of pattern. These and the high pitch roofs would be anchored so that wind didn't blow them away. Even the stairs were of mud, slightly steeper so that these took little space.

Roads were narrow and laid with brick, with proper drainage along the paths following the natural slope. These were all urban like, yet much neater. People were very friendly. Every house we wanted to enter they would gladly say yes, open their doors wide, and entertain us with muri and khejurer guur. It was really exhilarating enjoying bhapa pitha in a rural uthan in winter! Yet our faculty made us document the architecture, people, spaces and the elements, faces and events, through measured drawings, sketches and photographs.

Each house had its own interior court not shared with others. None of the houses looked similar; it was as if they were each designed by different architects- the creative and indigenous people of the village. Some houses were small, some were huge, each one had a different kind of style of attaching the corrugated tin pitched roofs to the mud walls. There was this one house at the corner of a street turning that had this big window and a lady in her forties was using this as a convenience shop to sell groceries to the locals.

The houses were also very responsive to the climate; although it was winter, at the time we were to complete our assignments, the sun was scorching. Yet the moment we stepped into any of these houses, we immediately felt a cool breeze and felt relaxed. It was as if the houses were air conditioned, only it wasn't stuffy, it was fresh air.

It was a real three hours of never-to-forget experience that we will bear in our mind whenever we design as what we experienced was a real piece of architectural beauty- down to earth architecture of the people that cannot be measured or compared with anything else we call beautiful. I wish we had our house and our school in such a setting, like the Rudrapur Deepshikha School in Dinajpur; a two storied mud house designed by Anna Heringer, a young German architect, who won the Aga Khan Award last year.

Unfortunately to our dismay we also found that many of the houses were now gradually being converted into brick houses with new tin roofs overhead, thanks to Grameen. This is threatening the survival of these splendid structures of ageless beauty and unparalleled spatial quality. Our faculty told us that he won a grant from National Geography a decade ago who could appreciate the architectural value of the vanishing art, and agreed to assist in documenting them. However, due to his leaving the country to teach abroad the final survey could not take place. But can we not declare this as our national heritage, protect it ourselves and ensure its continuation?

Also, we planned to visit Nasir Charitable Trust Clinic in Hatubhanga Kaliakoir on our way back. It won the Berger Young Architects Award in 2005. Our bus broke down. And we were literally stranded in the middle of a mustard field for seven hours until a rescue bus came for us from Dhaka. When the last person, that was the accompanying faculty, got down in front of his house, it was half past one in the morning.

|