|

Book Review

Into the Gloom

John Mullan

Enthusiasm and delight greeted the publication of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. Elaborately stage-managed as the hoopla might have been, no one can doubt the excitement of all those children queuing for their copies. But then none of them had yet read the book. For, in truth, this sixth Harry Potter novel is designed to dampen any readerly high spirits. Concluding inconclusively, with puzzles unresolved and prophecies unfulfilled, there may be plenty to guarantee the mega-sales of number seven, which will complete the sequence. Yet Harry Potter's fulfilment of his destiny has now become grim-faced. "There was no waking from his nightmare, no comforting whisper in the dark that he was safe really." This is from the end of the novel, a gloom not to be dispelled.

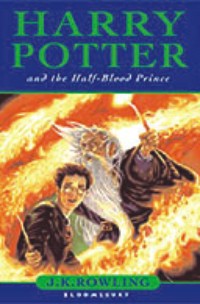

Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince JK Rowling |

Some might feel a little like Ron Weasley when he sees Hermione Granger reading the unreliable, indispensable wizard tabloid, the Evening Prophet. "Anyone else we know died?" enquires Harry's bosom pal, with a "forced toughness" in his voice. Well might he ask, for the body count has been mounting. Just as Jane Austen's sixth novel, Persuasion, was full of deaths, so is Rowling's. It begins, in the non-magical world of us Muggles, with reports of murders and "dozens" of fatalities from a collapsing bridge (arranged somehow by the wizard villain Voldemort). It ends with the notably unconsoling funeral of one of her chief characters. In between there are plenty more deaths put on by cunning and forced cause.

There have been deaths before in Potter novels: the very first one tells us of the killing of Harry's parents in its opening chapter. Now all the characters are prone to what Hermione bluntly calls "survivor's guilt". The deaths scattered through the previous Potter novels return in their minds to produce a prevailing mournfulness. Psychologically speaking, most are clad in inky robes. Rowling has spoken a good deal about her characters growing older, and now that Harry, Ron and Hermione are 16, the almost oppressive awareness of mortality is clearly a novelistic aspect of their maturity. Adolescence is anything but cheerful.

There is an awkwardness about all this, as if Rowling knows that while some readers have grown older like her characters, others are still children. Because of them the accounts of post-pubertal couplings must still be improbably chaste. Ginny describes Ron and Lavender "thrashing around like a pair of eels", but it is all just a bit of kissing. Younger readers will also miss Rowling's often deft sex-comedy. Parental readers, in contrast, will find Ron's amours ludicrously familiar. His passions are as shallow as they are solemn. Victim of a misdirected love potion, he spouts delicious claptrap about the girl who has brewed it, and then, having been given an antidote, slumps into the disconsolate attitudes of a paramour disabused. All in an evening.

Comedy has always been Rowling's special factor. The business of being trainee wizards fills her books with magical cock-ups and pratfalls, and there are some good episodes of spells gone wrong here, some written with an eye on cinematic treatment. There are also some reliably droll personages. Professor Trelawney, the sherry-tippling clairvoyant, is good for several laughs.

The usual elements are still there. It has been a strength of the Harry Potter books, as well as their severe limitation, that they remind you of their ingredients. Professor Slughorn's potions class, where the pupils strive to achieve a magic effect from just the right combination of elements, is surely Rowling's wry allegory for the business of becoming the world's most successful novelist. Here is a tincture of Narnia, an echo of Jill Murphy's The Worst Witch, a borrowing from Lord of the Rings (Harry has a baleful, slavish minion called Kreacher who is surely another Gollum) and a surprisingly large ladleful of Mallory Towers. Other readers will find their own bits of the recipe. A weighty review of Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in the London Review of Books detected Arthurian romance, Lewis Carroll and Freud's case histories.

This novel is built around a series of meetings between Harry and Dumbledore, the Hogwarts headmaster, where the great wizard and his apprentice have a pronounced tendency to explain the rules and anomalies of magic to each other. If they understand all, good might triumph. After all, why should evil be defeated? As Fudge tells the British prime minister: "The trouble is, the other side can do magic too." So the workings of magic must sometimes depend on the intelligence and virtue of those who use it. Harry and Dumbledore magically revisit the past and try to divine Voldemort's devilish schemes by understanding his past. Family history is all. Their meetings are the marrow of the narrative, for they combat evil without much help from others. When they are not together, you feel the plot is lost.

The odd glumness of this novel is partly a consequence of its loss of a satisfying plot, its lack of shape. There is, I think, a clear reason for this, evident from the amount that we have been hearing about Rowling's plans for her characters. We must not think that she is making her stories up on the hoof, even though the idea of there being seven books, one for each of Harry's years at Hogwarts, must have come to her only belatedly. She has become so fixed on the overall sequence of her novels, that the narrative shape of this one book is no longer a concern. She is working out some prophetic scheme. But it has become a hard task. It is difficult not to think that, rich and adored, JK Rowling's gusto has gone. Now she is just, like her hero, set on completing the grand scheme. Into the gloom she is determined to take all those devoted readers.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |