A promise, as dawn breaks in winter mist

Syed Badrul Ahsan

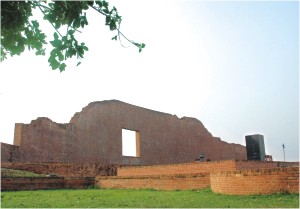

They were among the finest of people in Bengali society. Between them, and among them, they straddled a whole wide region of cultural ideas and political aspirations. They embodied the nationalism that had come to be associated with the ethos of this country since it was first felt, through the Language Movement of 1952 and then in the course of the Six Point movement for autonomy, that Bengalis needed to branch out on their own, towards a distinctive, sovereign political identity. And as with all men and women who come to symbolise the ambitions of a nation, who represent as it were the voices calling for change, they made the supreme sacrifice. All of them were systematically, carefully picked up by the local collaborators of the Pakistan army and then ruthlessly picked off. Rayerbazar remains a testament to the sufferings of these brave Bengalis. It is also a reminder, in much the same way that Auschwitz and Buchenwald and Dachau are reminders, that the spirit of a nation is never snuffed out through a murder of its bravest and brightest. The spirit simply passes on, to those who remain to carry the torch forward.

It is this torch we bear, have borne all these years since the liberation of Bangladesh on a December afternoon in 1971. Note that those who murdered these illustrious people have lived on, have even thrived at the expense of this free country. But they have done so in all the shame and humiliation we have heaped upon them for the murder they caused of their own people. It matters little that these men of outfits calling themselves Al-Badr and Al-Shams have through the years aged and even made it back to society, thanks to the machinations of some we thought knew better. It matters not at all that these men have been part of government, live on in the corridors of government. What does matter is the way in which we have kept them at arm's length, have indeed reminded ourselves at every point that an association with quislings is essentially a betrayal of trust with those who gave their lives for a country in order for the rest of us to live in freedom. When individuals like Alim Chowdhury, Professor Ghyasuddin, Selina Perveen, Nizamuddin Ahmed, Shahidullah Kaiser and all those others marched to the dark passages of death on the eve of liberation, they only reinforced the message that nationhood acquires poignancy and a sense of being through the willingness of men and women to make the supreme sacrifice of embracing martyrdom. It is this torch we bear, have borne all these years since the liberation of Bangladesh on a December afternoon in 1971. Note that those who murdered these illustrious people have lived on, have even thrived at the expense of this free country. But they have done so in all the shame and humiliation we have heaped upon them for the murder they caused of their own people. It matters little that these men of outfits calling themselves Al-Badr and Al-Shams have through the years aged and even made it back to society, thanks to the machinations of some we thought knew better. It matters not at all that these men have been part of government, live on in the corridors of government. What does matter is the way in which we have kept them at arm's length, have indeed reminded ourselves at every point that an association with quislings is essentially a betrayal of trust with those who gave their lives for a country in order for the rest of us to live in freedom. When individuals like Alim Chowdhury, Professor Ghyasuddin, Selina Perveen, Nizamuddin Ahmed, Shahidullah Kaiser and all those others marched to the dark passages of death on the eve of liberation, they only reinforced the message that nationhood acquires poignancy and a sense of being through the willingness of men and women to make the supreme sacrifice of embracing martyrdom.

Thirty six years after the emergence of Bangladesh, we pay tribute to all these soldiers of freedom, all these individuals whose contributions, had they not been pushed to a gory death, would have strengthened our hold on destiny. As we remember them, remember the contributions they made to our lives when they lived, we are also assailed by all those questions and doubts that arise in men when they spot justice being on the run and the perpetrators of grisly crimes getting away from it all. In the early days of freedom, as the state of Bangladesh sought to solidify itself, it was the natural expectation that those who had committed war crimes would be dealt with in terms of the law. Let us not forget that three million Bengalis lay dead, two hundred thousand women stood divested of their dignity and a whole geographical landscape lay witness to the horrendous crimes of the Pakistan army and the murderous elements it chose to call razakars. It was such truths, and others, that ought to have been confronted head on, through bringing to justice everyone who had involved himself in all such crimes against humanity. The crime of genocide is everywhere a sending out of a message that humanity has been debased, that human dignity has been torn to shreds and so needs to be handled in the only way possible, though a recourse to the law. There was the instance of Nuremberg before us. There were the examples of how escaped Nazis were still being tracked down and brought to book in the early 1960s. In more recent times, the instances of the war crimes tribunals on former Yugoslavia and Rwanda remain a sign of how unwilling the civilised world remains about letting crude bygones be bygones.

In Bangladesh, despite all the evidence, all the written and oral testimony about the criminality of the occupation army and its collaborators, despite the enactment of a Collaborators' Act in 1972, the murderers of our intellectuals, indeed of Bengalis across the board, were to go untracked and unpunished. That sadness would then turn to horror when the nation's first military regime, headed by a freedom fighter, decided in its questionable wisdom to do away with the Collaborators' Act and allow former allies of the Pakistan army back into politics. By the early twenty first century, some of these elements were in government. It was a moment of supreme irony: men who had through kidnapping and murder sought to flush out the idea of a free Bangladesh from Bengali souls cheerfully enjoyed the perks of power and authority in a land they had tried damaging through twisting the knife inside some of its most illustrious citizens. And irony mutates into the bizarre when a superannuated civil servant, not batting an eyelid, brazenly informs free Bengalis that what they went through in 1971 was a civil war. An ungainly bunch of rightwing academics, reinforced by courage that sometimes defines the ignorant, see not a liberation war but a military conflict between India and Pakistan in 1971.

You ask, this morning as you bow your heads before the souls of those who died on the eve of freedom, why things have come to such a pass. The answer, you will soon discover, is easy to come by: one government after another has failed to uphold the heritage we so assiduously built in 1971. And there is more. The nation's political forces have over the decades squandered their energy over an unremitting, intense struggle for power without noticing that even as they engaged themselves in that sordid dash for the heights, it was the old enemies of freedom who organised themselves, solidified their fortress and made ready to renew their long-ago assault on Bengali pride.

Which sends out a powerful, purposeful message to all Bengalis: it is time to turn around, face the enemy and send him packing through the woods he has so long inhabited. And that will be our way of paying tribute to the intellectuals who fell to the chicanery and depredations of the Pakistan army and its local collaborators only days before Pakistan died on the blood-soaked free land of Bangladesh.

As dawn breaks across a Bangladesh draped in winter mist, we make a promise, to ourselves and to those who lived among us and then passed on to glory made eternal through dying for freedom --- that we will redeem the past and reclaim our heritage through cleansing this land of the sinister shadows and cadaverous presence of those who once killed and raped and pillaged Bengal. It is not too late for the wheels of justice to turn. It is never too late for the souls of patriots to rest content in the knowledge that their Sonar Bangla is in the safe and secure hands of their fellow Bengalis.

....................................................

Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor, Current Affairs, The Daily Star. |