|

||||||||||||||||||

Poverty continues to push children out of schools Mahbubur Rahman Khan

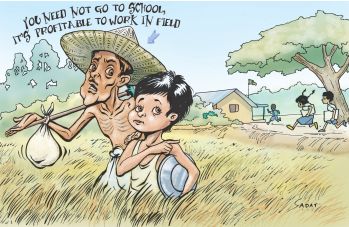

Sultan Ahmed, 13, collects plastic bottles littered on the streets. His earning at the end of the day stands at Tk 70-80. Sultan can write some names including his parents' both in Bengali and English and has a little knowledge of counting as he studied up to class four in a primary school. “I went to school regularly. When I was in Class IV, my father (who was a rickshaw puller) died in a road accident. I'm the eldest son of my mother who works as a domestic help. Now, I don't find any importance of going to school. If I go to school, my little brother and sisters will have to starve,” Sultan said. He then disappeared with other scavengers in search of 'goods.' Primary school dropout rates in Bangladesh though have come down, a significant proportion of children still remains out of school. According to Bangladesh Primary Education Sector Performance Report (ASPR-2012) over 18 million student are enrolled in all types of formal school 89,712 schools. About 2.6 million children are still being deprived of the light of education who are aged between 6 and 10 . (Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006) The Net Enrollment Rate (NER) for boys is 10 percent less than girls, while the Net Attendance Rate (NAR) for six year olds is 15 percent below than national average at 81 percent. The NAR, however , varies from one region to another of the country. (MICS 2009) Rakhi Aktar Swarna lives in a slum at the Kathalpotti of capital's Jatrabari area with her parents. She went to the Jatrabari Primary School until last year. “I am 13 years old now. My father asked my mother not to let me go to school,” she added. Swarna's father Boshir Ahmed, who works in a rice warehouse, told that his daughter is grown-up. “Now, if I continue to send her to school, she may become target of local goons who would harass her. That would be humiliating for us. Besides, my wife is pregnant and badly needs her attendance”. There is no single cause of dropout rather children leave school for multifaceted reasons. Experts opine that poverty influences the decision. Poor parents find it more beneficial sending children to work rather than school. Dr Siddiqur Rahman, consultant at National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB), blamed unattractive learning method as one of the prime causes for the dropout of children from school. “Children learn their lessons without understanding it. As a result, they don't find interest in school”, he said. Distance is another factor; experts believe it is a strong ground for dropping out of female children from primary education. Poor facilities, overloaded classrooms, inappropriate language of instruction and security are other common causes for school dropout. According to Dr. Rahman, the high proportion of dropout of children from school is not only causing huge resource loss but also hindering the progress in achieving educational goal or MDG. RTM (Research Training and Management International) conducted a study “Participatory Evaluation: Causes of Primary School Dropout” in 2009 on behalf of Directorate of Primary Education where some recommendations were made. The recommendations include 100 percent stipend, sensitization of parents about the need for education and criteria of stipend, introduction of tiffin, supply of free stationery, stopping of child labour, social mobilization, increased number of trained teachers, and effective home visits by teachers. The study recommended that the participation of local government, proactive SMC , training of SMC on role and responsibilities, strengthening of monitoring and supervision, award to meritorious students and improved teacher-parent-community relationship can also contribute a great deal in preventing dropouts. It also recommended for the improvement of infrastructure, and road communication, supply materials for children for games and sports, timely distribution of text books, and teachers residing in or near the catchments. On the above recommendations, suggested actions include gradual increase in coverage of stipend especially increasing the proportion in poverty-prone areas, undertaking social mobilization programmes to increase awareness of parents in remote and hard to reach areas, enhance inter-ministerial cooperation to minimise child labour by enforcing child labour laws, extending the Reaching Out-of-School Children programme in high dropout areas, identifying poor infrastructure of school buildings and prioritise establishment of school buildings, external evaluation to assess the quality of teachers' training, upgradation of teachers' qualification at entry level, ensuring participation of local government, ensuring regular and timely attendance and departure of teachers, strengthening monitoring and supervision and building school-community-family partnership. To address the situation, the government with the help of development partners including UNICEF adopted Primary Education Development Programme- PEDP III for five years from July 2011. PEDP III encompasses all interventions and funding that support pre-primary and primary education up to Grade-5. It has four components -- quality learning and teaching, participation and disparity reduction, decentralisation and effectiveness and sector planning and management. The above components are exposed to address the objective of an efficient, inclusive and equitable primary education system delivering effective and relevant child-friendly learning to all children from pre-primary through to Grade V of primary education. The PEDP III will give special attention to support equitable outcomes for all school children irrespective of gender and physical and mental ability, socio-economic conditions, geographical location and ethnicity. According to PEDP III, Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) and the Bureau of Non-Formal Education (BNFE), under the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, will share the responsibility of reaching out to the out-of-school-children with alternative or second chance education of quality through partnership with NGOs for gradual reduction in their number. BNFE, as a part of PEDP III, is planning to cover 93 percent of the total urban out of school children aged 10-14 years which is approximately 1.5 million children in urban areas of 64 district and six divisional cities of the country. NGOs are also playing important roles in delivering pre-primary and primary education, especially among the poor. NGOs such as BRAC, Save the Children, Plan Bangladesh, Phulki, Jagoroni Chakra, Dhaka Ahsania Mission are providing pre-primary education. BRAC operates more than 38,000 non-formal primary schools covering 1.2 million students. It is expanding its intervention to urban areas also. Under the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education's (MoPME) leadership Reaching out of School Children (ROSC ) project is providing non-formal primary education to out of school children in rural areas while the Basic Education for Hard-to-Reach Urban Working Children (BEHTRUWC) project is providing non-formal primary education to out of school children in urban areas. UNICEF is providing technical support to the government in its different programmes on reducing out of school children in urban areas. From 2004-2012, UNICEF gave non-formal education for 3.4 year to 166,000 children aged between 10 and14 years under the BEHTRUWC project. Several programmes are currently going on to address the problem of dropout. The programmes include continuing pre-primary education course, following-up the attendance, continuing involvement and participation of school management committee and providing incentive. If the quality of education could be enriched, students will show interest in schooling, said Siddiqur Rahman. He, however, observed that quality could not be changed overnight. Primary education still plagued by problems Pankaj Karmakar

Despite different government and non-government initiatives to enroll all the primary age children into school, approximately three million of them currently remain out of school due to a number of barriers and challenges. The barriers mainly include -- regional disparities, poor quality education, limited opportunities, government's low budget on education (Bangladesh allocated 2.6 percent of GDP while other South Asian countries up to 6 percent), family's economic need, policy gaps, lack of flexible time for schooling and lack of programmes addressing the real needs of children. Due to poor communication system and geographical remoteness, retention rate of children in primary schools is lower in haor and char areas by 8 percent, in hilly areas by 3 percent and indigenous-dominated areas by 2 percent than the national average of 81 percent, according to UNICEF statistics. Regional disparity and communication disadvantages cause a wide variety in children's attendance in schools among different regions. Net Attendance Rate (NAR) varies by 12.8 percent between the six divisions, 16 percent between slums and regional average and 21 percent among the 64 districts, according to Rasheda K Choudhury, Executive Director, CAMPE. Poor quality of education (often considered not appropriate by experts) acts as a major hindrance to children's enrolment and retention in schools. Curriculum has been designed in such a way that children have to learn only through memorising method. Children very often lose interest in learning due to the boring method of memorising. They want to learn though a fun learning method. They want to learn through photographs, games and sports and other sorts of amusements. Moreover, the teachers in many cases give lessons in such a way that it seems boring to children. They lose interest in attending classroom. Children will be interested to attend classroom whenever they find amusement. Teachers should be trained up properly so that their method of teaching and delivering lecture are more lively and amusing. Different sorts of amusing topics should be included in the textbooks so that the children get interest in reading the topics, experts believe. There should be a linking mechanism between formal and non-formal education to enhance opportunities for children to get enrolled in schools. The government's budgetary allocation for education is also very poor. Due to lack of financial support, the quality of education cannot be improved as per expectation and logistic support for children cannot be provided properly. While the government spends around 2.2 percent of total GDP (gross domestic product) for the education sector, experts suggest for allocating at least 6 percent to get expected results. In many schools, there is scarcity of classrooms, seating arrangements, teachers and other logistic support. These crises cannot be addressed without increasing budgetary allocation. However, to address the constraints, a project titled 'The Primary Education Development Programme-PEDP III ' has been launched on July last year to be continued till June 2016. Ministry of Primary and Mass Education coordinating, while ten donors including Unicef are providing fund. PEDP III encompasses all interventions and funding that support pre-primary and primary education up to class five. The project has four components -- Quality learning and teachers, participation and disparity reduction, decentralisation and effectiveness and sector/programme planning and management. When many of the countrymen live below the poverty line, the government is trying hard to establish Bangladesh as a middle-income country by first half of the next decade. But the people, who live below the poverty line, think that it would be more mature and a wise decision if they could engage their male child in profit-making activities instead of sending him to schools. So, as soon as the male child starts growing, parents engage him in farming lands, fishing or other sorts of informal jobs so that he can support his family financially. In case of female children, the situation seems to be worse because they are married off at an early age. Parents think that educating girl child is a wastage of money. That is why, community participation is very much important to ensure enrolment, attendance and retention of children in schools. Policy gaps of the government acts as another hindrance for enrolment of children in schools. The government formulates the same policy for all the children of the country. But the children of remote area, ultra-poor families and other underprivileged sections need to get more focus compared to the children of privileged sections and urban area. The government should formulate policy targeting the geographically disadvantaged people, providing more stipend to the ultra-poor family children, addressing the language gap of indigenous children and other sorts of disparities. Another major problem is inflexible time of schools. In rural areas, most of the male children have to help their fathers in land farming or other jobs, while the girl children have to help mothers in household chores. The school timing and schedule of these household activities appear to be conflicting because both have to be done at the same time. If the children get flexible time, then their enrolment, attendance and retention in schools will surely be increased. So, it seems that only education interventions are not enough to address the issue of OoSC (out of school children), rather it needs to be addressed with many other co-related factors. 'Initiatives have been taken to address the dropout problem' Shyamal Kanti Ghosh, Director General, Directorate of Primary Education, talks to The Daily Star

To ensure primary education for every child and prevent dropout all the stakeholders should perform well from their respective positions, said Director General of Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) Shyamal Kanti Ghosh. “The government alone cannot be able to reduce the number of dropout children”, he said adding, there are many factors which propel school dropout. The child dropout rate was 45.1 percent in 2008. The rate stood at 29.7 percent in 2011. “The dropout rate has been reduced by about 20 percent in the last three years. I hope it will be reduced more in the coming days”, Shyamal Kanti said. “Whenever a student leaves school, it is counted as dropout. But that boy or girl may join a madrassa or any other type of school. This possibility remains out of our consideration”, he said claiming, the dropout rate would be lesser if this factor is counted. Stressing the necessity of primary education, the DPE DG said that primary education is a rudimentary stage which creates skill among children. “It is the stage where a child learns how to count or how to write or sign. It helps them to become self-dependent in their next stage of life”, Shyamal Kanti maintained. He said the problem of dropout is common in remote, inaccessible and poverty prone areas. The DPE DG also held lack of consciousness, parents' immediate expectation for financial gain and non-availability of books responsible for children's inclination for dropping out from school. He said that the government is committed to ensure the rights of basic education for the children. “To fulfil this commitment the DPE is implementing a sector-wide approach -- Primary Education Development Programme (PEDP-III) -- for the purpose of improving the quality of primary education in the country”, he added. Several initiatives including improvement of education quality and teaching quality have been taken under PEDP- III to address the child dropout problem, he said. “When a student remains absent from school at a stretch for three days, teachers are sent to the respective child's resident to bring him/her back to school”, said Shyamal Kanti. Parents, especially mothers, are encouraged to send their children to school through motivating rallies for mothers, the DPE DG said in response to another question. “To draw and retain children's attraction, new books are supplied to every child from class I to V. Teachers are given training so that they can make lesson attractive to the children as a part of the PEDP-III”, said Shyamal Kanti. Mentioning that earlier only handful of students got scholarship, the DPE DG said about 50-90 percent student at primary level are now being given scholarship considering their family condition. People should consider it as their moral responsibility to send children to school, he observed. “A neighbour or relative should push a child if he stops going to school. They should try to find out the reasons why the child stops going to school and solve that. In the process, the dropout problem will be resolved”, said Shyamal Kanti. “I will be the happiest man on the day the dropout rate drops to zero”, he added.

'Government should increase stipend for the underprivileged children' Rasheda K Choudhury, Executive Director, Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), talks to The Daily Star

Bangladesh has achieved significant progress in terms of enrolment in primary schools, but retaining them in schools to complete the primary cycle remains a major challenge, said child education rights activist Rasheda K Choudhury. Apart from four exceptional groups of pupils, almost cent percent enrolment of children has been ensured in Bangladesh currently, she said. The exceptional four groups -- include children from hardcore poor families, children with disabilities, children of some special communities like gipsy, fisherman or sex workers and last one group is children of remote geographical locations or hard-to-reach areas. "Around one-third of the total children, who enrolled in class one, dropped out before they completed their primary education. "We do not know that in which class -- two or three or four -- they dropped out, but we cannot find them in the final stage of primary education," said Rasheda K Choudhury, executive director of Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE), the coalition of more than a thousand education NGOs, researchers and educators. Enrolment rate of children is lower in different special geographical areas compared to national enrolment rate. The special areas include char and haor areas, tea gardens and hill districts, she said. Due to long distance of schools, children and their parents often not get interested to enroll in schools. "In many areas, children have to reach school after walking around two hours. How can the parents become interested to send their little ones to school," argued Choudhury. So, it is very important to increase the proximity of schools, she said, adding, "There are still around 2,000 villages in the country without schools." The rate of enrolment in slum areas is also lower compared to national average. There are many floating children in urban areas. They move from one slum to another causing a major hindrance to their receiving basic education, she said. Talking about non-formal education system, Rasheda said, "It is the government's responsibility to provide basic education for all children. Whenever the government fails to do it properly, it is necessary to have non-formal education." Citing examples, she said, suppose a government-run formal primary school will not allow any child, who has become eight or nine years old, to enroll in class one. Then, how the child will get education? That's why non-formal education is so important, she said. She also stressed the need for better coordination and effective equivalency framework between formal and non-formal education streams. Talking about the policy gaps of the government, she said, "The primary education system is very much centralized in Bangladesh. The whole system is governed from Dhaka. I would like to request the government to decentralise education management and use the local government division for better functioning of the system." The government should formulate policy targeting the really underprivileged children and should increase facilities like stipend for them. She also urged on commitment of all political parties for improvement of primary education. "There is a culture in Bangladesh that a political government abandon different initiatives of the previous government. We want the culture be avoided in the education sector for the development of basic education," she said. Asked about the role of civil society members, she said they also can play important role to ensure cent percent enrolment, attendance and retention of children in schools. They can act a pressure group for ensuring effective measures and community participation in development. Rasheda K Choudhury also recommended ensuring child-friendly classrooms, developmentally appropriate reading contents, and child-friendly teachers for raising and retaining interest among the children to attend schools. Slum children largely left out of schools Staff Correspondent

Many Slum children in urban areas are deprived from education due to poverty, lack of coordination between formal and non-formal education, insufficient opportunities and lack of government's cordialness Currently around 41.7 million people are living in urban areas, 28 percent of the total population of Bangladesh, said a report titled 'The State of the World's Children-2012' by UNICEF. Around 18 percent of children in slums attended secondary school in Bangladesh. But no data were available about the slum children's enrolment at primary level, said the report. However, a paper prepared for the 10th UKFIET (UK Forum for International Education and Training) International Conference on Education and Development, 2009, showed that the net primary enrolment rate was around 70 percent in Dhaka city's slums. The prior problem of ensuring basic education for slum children is that slum populations are simply not recognised in the formation of policy or educational planning. For instance, there are no realistic estimates of how many school-aged children live in these areas, although the number is increasing rapidly. The government may be reluctant to recognise slums fully because this would mean recognising its obligation to provide services including education, and providing more services could draw more people to the city, said the paper. Another UNICEF report titled 'Basic Education for Urban Working Children' that was updated in September, 2008 said, most working children cannot afford the time to attend regular schooling. Because these girls and boys do not have access to education, they become trapped in low-skilled, low income jobs, which further push them into the vicious cycle of intergenerational poverty. Inter-city and internal migration is common among people living in urban slums, home to most of Bangladesh's urban working children. Landlords often have no legal right to the slum land where they build houses, so evictions are common. Civic unrest and employment instability also force families to migrate both within the city and across the country. These patterns make for high drop-out rates among those urban working children who manage to enroll in school, the report said. Rasheda K Choudhury, Executive Director of CAMPE said, "There are many floating children in urban areas. They move from one slum to another slum which causes a major hindrance in their receiving basic education, and increases dropout rate." Although a section of slum children get enrolled in schools, the attendance rate is lower than the national average attendance rate. The Net Attendance Rate (NAR) varies by 16 percent between the slums and national average, according to a UNICEF statistics. Visiting slums and analysing data, it becomes clear that many children living in urban poverty are clearly disadvantaged and excluded from basic education. Talking to this correspondent, an 8-year-old child Shipon, who lives in Rayerbazar slum, said he wants to go to school, but his family does not allow him. "My mother sells daily meal to working people like rickshaw pullers, truck drivers, day labourers and others. I have to accompany my mother in her business. For example, I have to bring water, wash plates and glasses, clean the wastes after taking food. That is why, I can not go to school," said Shipon. Shipon's mother Reshma Akhter said, "If my son does not help me in my business, I will have to appoint another boy with the cost of Tk 100 or Tk 150 daily. I cannot spend such extra money because I have to run my family with my income." Another child Alamgir aged around 10, who was seen gossiping with around a dozen of kids of his age at Kamalapur railway station, said his family came to Dhaka around six months ago from Barguna rendered destitute by river-erosion. "We have no accommodation for staying at night in the city. How I will go to school," asked Alamgir. Shipon or Alamgir are not the only ones faced with such circumstances, but hundreds of slum children are deprived of education like them. Talking to The Daily Star, Dr. Erum Mariam, Director of Institute of Educational Development of BRAC University, said “The number of schools in slum area in Dhaka and Chittagong is not sufficient against the demand.” More government schools and non-formal schools by NGOs should be set up in the slum areas to ensure access to basic education for all the slum children, she said.

|

| Previous Issue |

© thedailystar.net, 2012. All Rights Reserved