25th

March 1971

A Bangalee in Karachi

Khademul

Islam

Actually,

for me the shock came on the 26th. At about

1:30, 2:00 of a brilliant Karachi afternoon,

the sun glancing off a pyramid of blood-red

pomegranates on the cart of the Pathan fruitseller

ambling through our government officers'

housing colony. I, Bonny (Irteza), Fahim,

Chotu (Javed) and Tony (Rashid) were standing

beneath the neem tree in front of Bonny's

house, chatting. We had been 'playing' cricket

on the road beneath the spreading shade

of the trees that dotted the colony, one

of us spinning the ball from eight yards

away, one batting, the other three very

close to the bat for the popped-up catch.

For the last hour the only noise in the

immense noon quiet had been the 'tock' of

ball on bat and our collective 'owzats'.

We

were the same age, 17, 18 years old. Tony

was Punjabi, Chotu was half-Punjabi, Bonny

and Fahim were Uttar Pradesh migrants, Karachi's

dominant demographic slice. I had lived

side by side with them these last six, seven

years, had done all the usual things with

them that boys growing up do. But we hardly

ever discussed politics. Which, however,

didn't mean we lately hadn't become aware

of it, especially after the 1970 election,

when suddenly Karachi homes were electric

with talk about the country's fate. It became

the dominant topic, front, center and back.

On newspapers, radio and television. The

Pakistan media breathlessly began to report

the latest Bengali outrage against the state,

Islam and the flag; commentators, especially

the Urdu ones, wrote that mobs were running

wild through the streets, that the Awami

League had lost control of things and Bengalis

were taking apart Pakistan brick by brick.

A photograph of Pakistani cricketers, led

by Intikhab Alam, running out of Dhaka stadium

was run over and over again. Dark, short,

chattering Bengalis, sticks, stones, riots

and a mindless rage.

We

were the same age, 17, 18 years old. Tony

was Punjabi, Chotu was half-Punjabi, Bonny

and Fahim were Uttar Pradesh migrants, Karachi's

dominant demographic slice. I had lived

side by side with them these last six, seven

years, had done all the usual things with

them that boys growing up do. But we hardly

ever discussed politics. Which, however,

didn't mean we lately hadn't become aware

of it, especially after the 1970 election,

when suddenly Karachi homes were electric

with talk about the country's fate. It became

the dominant topic, front, center and back.

On newspapers, radio and television. The

Pakistan media breathlessly began to report

the latest Bengali outrage against the state,

Islam and the flag; commentators, especially

the Urdu ones, wrote that mobs were running

wild through the streets, that the Awami

League had lost control of things and Bengalis

were taking apart Pakistan brick by brick.

A photograph of Pakistani cricketers, led

by Intikhab Alam, running out of Dhaka stadium

was run over and over again. Dark, short,

chattering Bengalis, sticks, stones, riots

and a mindless rage.

We

Bengalis of course looked at things differently.

But only inside our homes.

'They

flew the flag,' I remember Mortuza Uncle,

an old friend of my father's in from Dhaka

for a couple of days in March, saying.

'Yes,

we heard,' my father had replied.

'A.

S. M. Abdur Rab,' Murtaza Uncle had continued.

'The time had come, he said, and raised

it.'

'Yes.

I think Jang ran a photo of it.'

'Ah,

it was fantastic, the roar that went up,

that flag fluttering out there.' My father,

who till the massacre had wanted autonomy,

not independence, for Bengalis, had looked

away. During the 1970 parliamentary elections,

when his elder brother had contested for

the seat from Feni (and had won), he had

proudly ticked off his vote in the absentee

ballot papers for himself, had watched as

my mother had ticked off hers, then had

promptly mailed them off.

This

was fascinating stuff for me. To be perfectly

truthful, it was only at the the end of

February 1971yes, I was that late--that

I began to revel in the force and might

of Bengali nationalism. Despite speaking

Bengali at home, eating rice every day,

having a father who wore a lungi at home

and mangled Urdu every time he spokea source

of endless hilarity for his childrenthe

living politics of East Pakistan had been

distant thunder in the sky. It was because

I went to an English-medium school, and

therefore was not a part of the Bengali

milieu within the colony, where intense

discussions about politics took place. The

majority of the Bengali kids my age went

to a specially-constituted Bengali-medium

school, and their circle, their books and

talk and interests, even jokes, were completely

different. There were a couple of Bengali

'boys' who had gone to English-medium schools,

and who had, like I and my siblings, assimilated

into Urdu-speaking West Pakistani culture.

As children growing up will. But from February

1971 onward I was drawn to the former group

like a moth to a flame. At Dr. Hasan's house,

which was a hotbed of political adda. Dr.

Hasan sat there pooh-poohing Sheikh Mujib

and the idea of Bangladesh ('Discrimination?'

he would shout, 'You boys have no clue how

Bengalis will practice discrimination on

fellow Bengali'; he stayed back in Pakistan

after 1971), while his sons would go for

his throat. I would sit there taking it

all in. And one day, somebody popped a cassette

into the player, turned it to full blast,

and a second later Sheik Mujib's 7th March

speech deafened us. I had never heard Mujib

before, and I remember the hairs on the

back of my neck stood up as I listened to

his voice. And which made his later betrayal

of ideals incomprehensible to me. But throughout

all this, never did I once think that it

would come to the slaughter that it did,

the killing fields of Operation Searchlight.

And

so for me, after February, as it had been

for other Bengalis much earlier, discussions

were confined to home. What was there to

talk about with Pakistanis? What would they

know about how Bengalis felt? Because even

if we did talk 'politics', we really wouldn't

be talking about politics; we would be talking

about hurt, anger, discrimination, betrayal,

racism, lying, and stealing.

This

taboo vanished in a flash as Bonny came

out of his house, where he had gone to drink

a glass of water, and said, to nobody in

particular, 'They arrested Sheikh Mujib

last night.'

I

was stunned. Nobody else said anything in

response.

After

some time I managed to get one word out:

'What?' And looked around. but they wouldn't

meet my eyes. Everybody looked away. Chotu

especially. However differently they might

talk among themselves, they now refused

to exult in front of me.

Then

Bonny spoke again, looking downward, 'The

army arrested Mujib. They are bringing him

here.'

Still

nobody would meet my eyes. It seemed impossible

to me. I hadn't been following the events

in Dhaka hour by hour (there was no way

to do it), but even if I had, it would still

have come as a thunderbolt. Perhaps, despite

my recent re-education, I still retained

an innocent belief that these people, whose

sons I played with, in whose midst I had

lived the last six or seven years, wouldn't

actually turn into barbarians overnight.

'How

do you know?' I asked Bonny.

'My

father just told me. He heard it on the

radio.'

I

stood rooted to the ground for several moments,

as somewhere a pyramid of flame-red pomegranates

came crashing down, then said 'I have to

go home.' Again, I have to confess that

it did not enter my head that Mujib's arrest

could be the prelude to a systematic assault

on civilians. That would come in the days

ahead, as stories of the attacks on Rajarbagh

police lines, on Dhaka university halls,

of teachers being shot, of neighbourhoods

torched by flamethrowers, of the entire

political leadership of East Pakistan disappearing

at a single stroke would transmit via the

Bengali grapevine. As did later the counter-news

of resistance, of a people united and fighting

back, of a spirit that was emerging that

was much fiercer than what was being inflicted

on them, of a guerilla war of attrition,

of stories of defiance and heroism. In fact,

Murtaza Uncle would again pop up in mid-July

1971 in our drawing room, to recount how

my uncle, Khwaja Ahmed, MNA-Elect from Feni,

same seat as the infamous Joynal Hazari

(oh, how things do come to a pretty pass!),

fought the Pakistan army as it advanced

on the town, managed to halt it for some

time, which gave him and his comrades-in-arm

time to empty the bank of money and cross

over to Agartala.

'Aray,

she ki juddho lichu bagan ai,' Murtaza

Uncle said, one leg crossed over the other,

slick head shining beneath a wall clock

that just then chimed as if in hearty approval.

March

26 would bring about the final alienation

from all things Pakistan, its ideology and

state, its mullahs and mosques, anthem and

Jinnah caps, from everything in the society

that throbbed and shuddered outside my bedroom

window. But all that still lay ahead, was

in the future. That midday with its diamond-bright

light, Mujib's arrest alone was enough.

Chotu,

who lived in the apartment building in front

of me, said he would come with me. And slowly,

my head down, shocked into absolute silence

I started the walk home. With Chotu, who

was later to join the Pakistan Navy and

rise upwards, beside me. I remember feeling

as if I was walking underwater, putting

one foot in front of the other very deliberately

on Karachi's hard, stony ground. This is

it, I kept thinking, and I felt it in my

bones, the point of no return. Either way

Pakistan was finished for me, for my family,

because the day the dust settled, as settle

it must, we either lived on as cowed slaves

here, which was unthinkable, or somehow

East Pakistan became free and we would move

there. Either way, this sun, this heat,

this sand, this Karachi, lying so quietly

all around me, this city with its horse-drawn

victorias and its museum full of Mughal

miniatures, its camel carts and glasses

of salty lassi, would soon be rendered a

fiction, would not be mine. Already it began

to seem unreal, these people here sleeping

and breathing and eating and leading their

lives so peacefully, so uninhibitedly, so

freely, while the voice of the Bengali people

was in shackles.

At

the entrance to our front gardenwe lived

on the ground floor of the four-apartment

blockI turned and went inside without saying

goodbye to Chotu, who sloped off without

a word either. Inside, on the verandah,

where we had our dining table, the whole

family plus 'Anis Uncle' (Anisul Haq, who

later in independent Bangladesh started

his own ad company, who died last year and

in whose memory his niece wrote a lovely

piece for The Daily Star), were just sitting

down to lunch. Anis Uncle, sitting with

his back half-turned to me, was chewing

his very first mouthful, some rice in a

hand poised in mid-air. The others were

about to start.

'They

have arrested Sheikh Mujib,' I blurted out.

Their

faces turned towards me. Eyes dilated, faces

draining of colour.

'Bloody

fascists, bloody fascists', Anis Uncle sputtered

in English as he sprang up from his chair,

rice spraying out of his mouth all over

the table. My father stared at me. 'They

said it on the radio,' I added.

I

remember noting that my father's and Anis

Uncle's eyes then acquired an oddly glazed

look as they absorbed the news, something

fatalistic, as when somebody's worst fears

are realized and there is no other place

to go to. It dawned on me that, unlike me,

they had been anticipating this. And now

were anticipating something far worse, something

that I couldn't quite grasp, and would be

beyond me for at least a day more.

'Sorry,

bhabi,' Anis Uncle eventually said to my

mother, who just nodded, 'for spoiling your

food. But I can't eat anything right now.'

He

went to the bathroom, washed his hands and

went to the drawing room, where my father

had also retreated to. Both of them lit

cigarettes and smoked and looked out of

the window, at the rose bushes nodding in

the heat. At the sky, almost white in the

glare. My mother, I, my brother and sister

sat and looked at them. Then a little later,

Anis Uncle said he had to go, and so we

all accompanied them outside and saw them

off to their car. Then turned and came back

inside.

Not

knowing what was going to happen next.

That

was my day of shock, my March 25th, 1971.

............................................................................................

The author is the Literary Editor of The

Daily Star.

A memoir of March '71

Ashfaq

Wares Khan

At

a point when the struggle for democracy

was rising to its peak and East Bengal was

fuming, a man who's fist would raise in

protest against the Pakistani colonial attitude

as well as grip the pen when asked to be

the brilliant economics student at Dhaka

University, he was at the core of the student

movement that was spearheading the fight

against the injustices perpetrated on Bangalees

in early 1971 was the then East Pakistan

Student's Union (EPSU) President Mujahidul

Islam Selim.

Now

the General Secretary of the Communist Party

of Bangladesh, Selim, it seems, hasn't given

up the struggle to find justice in the country

that he loves. Back in the early months

of 1971 the demands were not much different

democracy and emancipating the toiling masses,

- but it contained one paramount objective:

autonomy for east Bengal.

Now

the General Secretary of the Communist Party

of Bangladesh, Selim, it seems, hasn't given

up the struggle to find justice in the country

that he loves. Back in the early months

of 1971 the demands were not much different

democracy and emancipating the toiling masses,

- but it contained one paramount objective:

autonomy for east Bengal.

Leading

up to the night of March 25th, Selim explains

the escalation of mindsets from the rage

on streets to taking up arms against the

Pakistani army was triggered largely on

March 1, 1971. For on that day, the dream

of democracy and to implement Bangalee's

demands through the elected government were

trampled by the abrogation of election results

by Yahya Khan. This act, for Selim, his

comrades and his leadership, turned their

focus to one goal: liberation at any cost.

"We

decided that if Yahya Khan impedes our path

to establish democracy, we will try to establish

the government that people elected even

if it means liberating Bengal as an independent

country," recalls Selim.

One

of the crucial and concrete examples of

this mindset, Selim notes, is when EPSU

was the first to officially introduce the

demand for "the right to cessation

and autonomous rule" in their manifesto,

and the medium to establish this people's

government, however, brought, for Selim

and a number his leaders, an armed struggle

on the agenda.

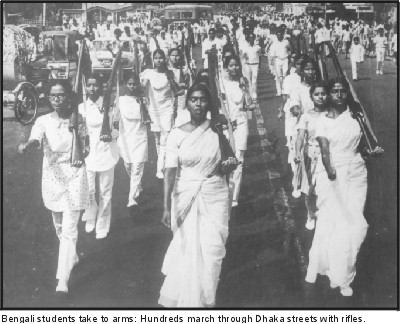

"We

then went on to secretly accumulate dummy

rifles to organise massive drills on the

playing fields of Dhaka University every

day with over a 1000 male and female students

enthusiastically participating in them,"

recalls Selim.

He

was also one of the main co-ordinators to

inform Dhaka-residents about the armed preparation

the students were taking for a confrontation

with the Pakistani administration, by organising

thousands of students with dummy rifles

poised tautly on their shoulders and martial

attires to march through rapt Dhaka crowds.

"The

streets were full of people who would stop

to look at us and fill their hearts with

pride, it also uplifted a lot of people

who were not aware of the resistance that

was being planned at that time. The message

spread like wildfire these marches and acts

of resistance were replicated throughout

the muffassils within a very short time,"

Selim remembers.

These

preparations led some members, including

Selim, to organise a bit more militant namely,

explosives and more advanced training with

live munitions.

"A

group of 15 or 16 of us (EPSU members) took

the initiative to set up a target practice

range in an uninhabited area in Damra on

the outskirts of Dhaka. There, we started

to experiment with live ammunition, and

experimented with assembling the materials

for powerful explosives by collecting chemicals

from Dhaka University chemistry laboratories,"

Selim adds.

That

group of 16, including some top student

leaders from EPSU at that time, failed the

first few attempts at detonating these bombs,

says Selim. But, their first cases of successful

detonations were made at a rubbish heap

next to Modhu's Canteen at DU on February

22 1971, Selim recalls.

Spurred

on by the blow of Yahya's denial of Mujib's

election victory, and buoyed by the wave

of students and people from all sections

of society participating in active resistance,

Selim was one of the masterminds for a more

ambitious plan that echoed the militant

and revolutionary voices of history.

Selim

smirks at what he considers now to be childish

and hilarious. He says that the most militant

and intense activists borrowed from the

strategies of resistance employed in the

Paris communes during the French revolution,

small-condensed resistance in metropolitans.

A mentality that could also be seen as a

precursor to the guerrilla tactics that

were to be employed during the war of liberation

itself.

"We

established strong and dense networks in

the suburbs of Dhaka city, where we distributed

handbills among the households, reaching

out to them in order to engage them in the

resistance by throwing everything at the

enemy from pouring hot starch-residue from

cooked rice, to spraying the enemy with

hot spices," said Selim. Reflecting

perhaps some of the naivete among the student

leaders but also a reflecting a depth of

thought in calculating all the available

options to resist the army.

At

that point, though Selim and his comrades,

knew politically that they had to prepare

for an armed struggle, albeit with primitive

strategies, they had no idea how barbaric

the attack would be or how modern both the

weapons and strategies of the Pakistani

army would be; they were just left to find

out in the next nine months.

At

that point, though Selim and his comrades,

knew politically that they had to prepare

for an armed struggle, albeit with primitive

strategies, they had no idea how barbaric

the attack would be or how modern both the

weapons and strategies of the Pakistani

army would be; they were just left to find

out in the next nine months.

From

the day Yahya declared that parliament will

not be allowed to sit, the students would

hold public briefing sessions every afternoon

on the steps of the Shaheed Minar to update

the audience of ongoing political events

and to announce political programs to activists

about political actions to be taken in different

localities the following day.

"On

March 25th, we started to receive news that

the Pakistani military were concocting some

sinister plans, and in the afternoon we

heard that Yahya and [Zulfiqar Ali] Bhutto

were set to leave Dhaka and that's when

we got the drift that a climax situation

was in the offing," accounts Selim.

Chronicling

the account of the 25th, Selim continues

"I clearly recall, on that afternoon,

we announced that the next briefing would

be tomorrow morning instead of the afternoon

and we need to amass thousands of students

and public, just not activists."

The

leaders, including Selim dispersed soon

after, telling other activists not to sleep

at homes in fear of late night arrests and

to keep a look out for further orders.

Selim

then went to a house of a fellow activist

where Chatra League, Awami League, Jubo

League, NAP, EPSU, and other activists alongside

renowned artist Kamrul Ahsan gathered to

discuss future plans for action.

"We

had a layman plan setting our eyes on blocking

Pakistani tanks entering the city around

Farmgate and blowing up a small culvert

in Kalabagan," said Selim. He added,

"We didn't have many modern weapons,

so we thought the only way to stop a tank

would be to take a Molotov cocktail close

to the tank and have it thrown into an opening,

it was naï

ve to think it would work, but it was the

only that was available to us!"

Then

an argument broke out over the priority

to protect either their locality or the

whole of Dhaka, but as they were arguing,

however, gunfights had already broken out

in their surrounding suburbs, and soon enough,

they were ringing in their ears in Hatirpool

it was half past seven in the evening.

"Unnerved,

we immediately called our leaders to ask

for a plan," Selim recalls. The plan

wasn't far from what they had they continued

with the basic plan to make molotov cocktails.

Hundreds

of empty bottles, a barrel of kerosene,

petrol cans, clothes to make the wick for

the cocktail, all appeared within a matter

of minutes, but just as they were about

to prepare the explosives they heard loud

explosions right outside their building.

Selim

looked out to see the densely populated

slum near the old-train tracks in Hatirpool

ablaze, and when the situation had become

more grim they decided to go up to the roof

to observe the current state of their locality.

"Stunned

by the array of tracer bullets going in

all directions all around us, we saw that

the army had occupied all the major roads

around us, while the wailing in the slums

were getting stronger," Selim goes

on to describe. But, he adds with concern,

"We were worried that if the army raided

our house, all our ingredients for the molotov

cocktails would be found, so we went about

quickly disposing of most of the materials."

Luckily,

a curfew was imposed around the same time

they had disposed of the materials. Gripped

by uncertainty, and the weight of future

responsibilities, Selim and the others were

not aware of what they were to see as they

emerged from the curfew early in the morning

and set foot on DU campus.

"It

was a macabre scene with scattered bodies

and destruction!" reconstructs Selim.

His experience and intuition as a politician

then impelled immediate action "We

made our necessary top internal contacts,

and dispersed quickly before the curfew

ended within two hours."

Selim,

then made his way out of Dhaka towards its

outer districts, for which he held an advantage.

Selim had a number of contacts with village

households from working as a relief worker

during the 1970 floods in villages such

as Trimohoni and Dakkhingaon. Following

instructions from top leaders of his party

Selim used the villages as a base to cross

the border into India. The households in

the villages that were close to Selim from

the 1970 relief days, then became hideouts

not only for his close friends, but also

some of the top leaders of his party. Subsequently,

becoming safe houses where the party and

EPSU leadership were to re-think their strategy.

"Politically,

we might have grasped the situation, but

as we came to think more and more about

the military aspects, we realised we couldn't

confront the modern weaponry of the Pakistani

forces without consolidating our force and

better preparation for a much, much bigger

war," says Selim on the state of planning

and preparation of the leaders and activists

during the end of March.

Selim

marched off to India to conclude the historic

month of March, 1971 and to face the other

challenging months to follow, Selim went

shoulder to shoulder with his comrades,

chased by bullets from behind, through Narsingdy,

Comilla, past Akhaura towards the Indian

border and the town of Agartala.

Nine

months later, after seeing his comrades

fall in battle, after becoming a senior

member of the Operation Planning Committee

of the eastern zone during the war of liberation,

Selim then became a part of the first group

to take a historic oath on the steps of

Shaheed Minar on Decemeber 17, 1971. It

was a long way from March, but Selim alongside

his comrades in arms and spirit, had seen

the first flames of independence and a new

path to march on for his country.