Feature

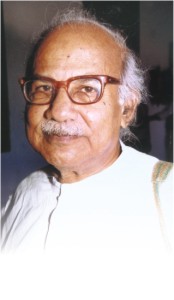

Waheedul Haq:

A Tribute to a teacher

Faiyaz Murshid Kazi

The first news I read that morning said that Waheedul Haq was in coma. The next morning, since it was a weekend, I put on my computer his CD album Shokol kanta dhonno kore, released by Bengal Foundation. The voice we had heard for so many years filled up my room, evoking a stream of memories of Waheedul Haq, of Chhayanaut, of my younger days. As I started humming the tunes with him, I was hoping he would make a comeback. The same evening I received an email saying he was no more. The first news I read that morning said that Waheedul Haq was in coma. The next morning, since it was a weekend, I put on my computer his CD album Shokol kanta dhonno kore, released by Bengal Foundation. The voice we had heard for so many years filled up my room, evoking a stream of memories of Waheedul Haq, of Chhayanaut, of my younger days. As I started humming the tunes with him, I was hoping he would make a comeback. The same evening I received an email saying he was no more.

I was never close to Waheedul Haq. I was never his disciple in that sense. I was a mere student of his in Chhayanaut, like so many others. He did once or twice ask me to go to his place so that he could help me understand and overcome my shortcomings in music. But somehow I never dared to seize the opportunity. I often thought it was my characteristic shyness or perhaps sheer laziness. But now I know better.

For a casual student like me, to sit through Waheedul Haq's class was like being exhumed by a sense of guilt. Every once in a while, he would remind us that music could not be a half-hearted affair. For him, there could be no compromise or dilettantism in Art. I guess I was only looking for teachers who would not be so “demanding” of me. And, that is why I could never have the courage to acknowledge Waheedul Haq as my guru. I would only envy from a distance his disciples who would be surrounding him all the time, making their own individual struggles to live up to his expectations.

After each bad performance on stage, his was the gaze I tried to avert by all means. He would just give a blank look and that would be enough to get the message. Perhaps he could not even bother to listen, but I always had a feeling that he did. It was on rare occasions that I caught a glint of approval in his eyes. The last time I performed on a Chhayanaut programme in Natmondol, he mumbled some words of appreciation. I was so beside myself with joy that I could hardly catch the words.

Waheedul Haq admonished us in class, but never raised his voice. To drive home his point, he just talked in his rambling manner, but never made it sound like a sermon. And, perhaps to remind us of where we were he broke into music every now and then. He knew there would be other teachers who would tell us about the grammar of music, introduce us to new taals and ragas, and show us how to read notations. It was his duty to make us feel the passion for music and unravel the world of beauty that could be conceived of the seven basic notes.

It felt as if he took a particular Tagore song to teach in the class only as a pretext. He would literally deconstruct the song to unearth the layers of meaning and then lead us unawares to explore the depth of Tagore's humanism and spirituality towards expounding his vision of Jivandevta. Waheedul Haq would sing the opening lines of the song and then break into a seamless alaap of the raga that the song was based on. He would show us how to articulate each sound, where to pause for breath, which word to stress to accentuate the meaning, or how to deliver the delicate shanchari or third stanza of the songs. He would talk to us about plants, about aesthetics, about quantum physics, about anything pertinent that crossed his mind. In my first year class of Chhayanaut, I just sat mesmerized, a schoolboy striving to make sense of half the things being said to us.

Waheedul Haq never discussed “politics” in class or even in private sessions with us. But he could relentlessly talk about what it really meant to be a Bangalee. For him, it was an urge or a feeling that should come from within, and had to be worked at continuously. Obviously, he underscored certain principles in the process, and seemed to have made it his life's purpose to instill these principles among his students. He threw us the challenge to espouse certain value judgments that may have seemed a little too “rigid” for our “postmodern” debates (e.g. high culture vs. pop culture), but we were always awed by the force and sincerity of his conviction. Of course, we could never confront him with these “debates”; for these are issues we need to negotiate among ourselves and this is an area where Waheedul Haq and his ideas will always remain relevant.

Three years ago, I finally started going to Waheedul Haq's Shewrapara residence along with some of our peers to take lessons from him. Waheedul Haq used to sit on his bed against the open window, with the early morning light gleaming on his silver hair. One of us would start strumming the strings of the tanpura, he would take some time to clear his throat and sing out Shokol(o)-kolush(o)-tamosh(o)-horo, joy(o) hok tobo joy/ Omritobari shinchon(o) koro nikhil(o) bhubon(o)moy. As he “chanted” those lines, to my admiring eyes he seemed to be transcending to a different realm. I think I can still distinctly hear his voice rising in “prayers” for the well being of the world he loved so much.

In some ways, I feel happy that I had known him only at a distance.

The writer is a former student of Chhayanaut

|