| Spotlight

Pools of Invisible Matter Mapped in Space

Jeanna Bryner

A new map reveals dense pools of invisible matter tipping the scales at 10 trillion times the mass of the sun and housing a cosmic city of ancient galaxies. A new map reveals dense pools of invisible matter tipping the scales at 10 trillion times the mass of the sun and housing a cosmic city of ancient galaxies.

The map, presented last week at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas, provides indirect evidence for so-called dark matter and how this mysterious substance affects galaxy formation.

Scientists theorize that dark matter, considered to make up about 85 percent of the universe's matter, acts as scaffolding on which galaxies mature. As the universe evolves, the tug from dark matter's gravitational field causes galaxies to collide and swirl into superclusters.

It's all these gravitational effects, from something that can't be seen, that indicates dark matter exists.

"The dark matter halos are what allow the galaxies to form in the first place. The dark matter is the underlying skeleton of the universe," said Meghan Gray of the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, who was part of the map-making team.

"Most of the universe is dark matter. Galaxies are just froth on this ocean of dark matter."

Uncovering invisible matter

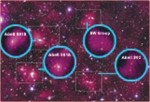

Gray, Catherine Heymans of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and colleagues used NASA's Hubble Space Telescope to observe a supercluster called Abell 901/902, which resides 2.6 billion light-years from Earth and spans more than 16 million light-years across. The astrophysicists measured light from a backdrop of more than 60,000 galaxies after it passed through the supercluster and its dark matter. According to Einstein's general relativity theory, the presence of matter can bend spacetime, deflecting the path of a light ray passing through the mass.

"Dark matter leaves a signature in distant galaxies" explained study co-author Ludovic Van Waerbeke of the University of British Columbia. "For example, a circular galaxy will become more distorted to resemble the shape of a banana if its light passes near a dense region of dark matter."

By averaging the shape-distortions from the thousands of galaxies, the researchers found four pools of dark matter. And the invisible clumps matched up with the location of hundreds of ancient galaxies, which have experienced a violent history in their passage from the outskirts of the supercluster into the central hubs.

"If the supercluster wasn't there, you'd still see all of these galaxies in the background," Gray told SPACE.com. "But you put this massive object [in front of them] and your view gets distorted. It's a cosmic optical illusion."

Aging galaxies

The survey's broader goal is to understand how galaxies are influenced by the environment in which they live.

"The new map of the underlying dark matter in the supercluster is one key piece of this puzzle," Gray said. "At the same time, we're looking in detail at the galaxies themselves."

The galaxies in the central hubs, they are finding, show signs of aging, as they are elliptical, red in color and are no longer forming stars. Disk galaxies reside on the outskirts of the supercluster. These youthful galaxies are blue-hued and buzzing with star birth. It's these young galaxies that constantly fall into the supercluster, adding to its galactic girth.

"As they come in, either they're interacting with each other more or they're interacting with the dark matter," Gray explained. "Something is happening to change their properties."

The team plans to study individual galaxies in an effort to understand how this supercluster environment shapes and changes galaxies.

The Developmentally Disabled Galaxy

A strange old galaxy churns

out new stars like a young'un.

Clara Moskowitz

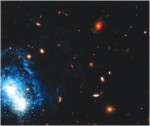

Although their lifetimes span billions of years, galaxies age, just like people. As rambunctious young'uns, they undergo bursts of star formation that create hot blue orbs out of the simple elements hydrogen and helium. As galaxies grow older, they settle down. Not only do their stars cool and become redder, but they eventually burn out and die, releasing into the galaxy heavier elements that formed in the stellar furnaces. Although their lifetimes span billions of years, galaxies age, just like people. As rambunctious young'uns, they undergo bursts of star formation that create hot blue orbs out of the simple elements hydrogen and helium. As galaxies grow older, they settle down. Not only do their stars cool and become redder, but they eventually burn out and die, releasing into the galaxy heavier elements that formed in the stellar furnaces. So astronomers have been repeatedly baffled by a peculiar, developmentally challenged galaxy called I wicky 18. When they first sighted it about 40 years ago, they thought it was a not-quite-billion-year-old toddler brimming with hot young stars, full of hydrogen and helium and possessing very few heavy elements, called metals. Finding such a young galaxy near others that are at least 7 billion years old thrilledand perplexedthe scientists. But new observations from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have revealed ancient stars mingled with the young ones, proving the galaxy as a whole is in fact as old as its neighbors.

Astronomers don't know why this galaxy is so low on metals, or why it's forming so many new stars so late in the game. It's possible that this relatively light galaxy has too little massor gravitational pullto retain the metals, and that a rush of gas called a galactic wind swept them away. Or maybe the galaxy's relatively isolated position caused it to develop slowly: There are few other galaxies around to help seed star formation.

They also don't know why it's not happening in all dwarf galaxies. “It's possible that there are more out there like this,” says Francesca Annibali, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who worked on the project. “If they are more common, then that means that some process is inhibiting star formation in small, low-metal environments.” Whatever the cause of I Zwicky 18's strange history, its close resemblance to primordial galaxies offers a unique opportunity to study how stars acted in the early universe, something that normally cannot be observed at such close range.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2008

|