| Spotlight

An Architect's Dhaka

Mahbubur Rahman

I came to Dhaka as a teenager to get admission in architecture after finishing my initial schooling at one of the cadet colleges about 60km from the city amidst some undulating Pleistocene period forest land, a land that carried myths and fables of Anandamath and Bhawal Sanyasi. It has been three decades since then, I'm not sure if that is enough, but I feel like Dhaka is my city. In fact the feeling came soon after my arrival in the city; it was a time when long hair or double riding in bicycles irritated law enforcers.

Dhaka was quiet; standing in front of Dhaka College you could clearly see the Mirpur Road straight up to Titas (Dhanmondi Road 5). Peddling from Azimpore, we could go as far as Sidheswari all the way under shaded trees, trees planted in early twentieth century as planned by Robert Proudlock, the landscape designer of Kew Garden that I had a chance to visit in 1987.

Within the very first week of my BUET days (22 years!!), I found tuition in an area called Nawab Katra near Chankhar Pul/Nimtali. I had no idea at that time what Katra was, that the term was derived from Arabic katara meaning residential quarter a cellular form around an oblong form, or there were many such Katra in Dhaka. After the first day teaching math I decided to return to my hostel at Palashi on foot partly because that was the only means I could afford, and more because I wanted to see and get familiar with Dhaka. So instead of taking the so called Asian Highway, I took a small lane parallel to it with the expectation that I shall be after a while in Bakhshibazaar from where I could easily find my way to my hall. Within the very first week of my BUET days (22 years!!), I found tuition in an area called Nawab Katra near Chankhar Pul/Nimtali. I had no idea at that time what Katra was, that the term was derived from Arabic katara meaning residential quarter a cellular form around an oblong form, or there were many such Katra in Dhaka. After the first day teaching math I decided to return to my hostel at Palashi on foot partly because that was the only means I could afford, and more because I wanted to see and get familiar with Dhaka. So instead of taking the so called Asian Highway, I took a small lane parallel to it with the expectation that I shall be after a while in Bakhshibazaar from where I could easily find my way to my hall.

It was dark; the alley was narrow, and there was no street light. What I didn't realize until after around half an hour, except that it was taking unusually long time, was that the lane was slowly turning. I suddenly came to an area with some lights on, and a mosque in the front with the Qibla towards my right. I was in fact heading towards south instead of west and reached somewhere close to the Central Jail.

Later I came to know that mosque was really old and famous- known as the Khwaja Nehal Masjid on Abul Hasnat Road near Muqim Katra. So that was the beginning of my love affair with old Dhaka and traditional architecture. But unfortunately awareness to rich traditional architecture that Dhaka or Bangladesh in general had was virtually absent until we were in our fourth year of studies. Students of architecture generally aspired to design international style buildings that could in fact be placed anywhere (in the world).

Though the roots of modernity in Bangladesh (in architecture) goes back to early 1950s, with Muzharul Islam designing the Art College, and subsequently to be followed by the Dhaka University Library, NIPA Building, and the Science Laboratory, Chittagong University and the Jahangirnagar University. Even within BUET campus, we had our own building designed by Vrooman, and there were the gymnasium and the new student's halls by Bouigh (who took the name of Golam Rab as becoming Muslim, and also designed the Kamalapur Railway Station, Notre Dame College Brothers Hostel, and St. Joseph School). At a stone's throw distance was the Dhaka University TSC designed by Doxiades, which we used to frequently visit to play table tennis and swim afterwards in not so pleasant water of the pool. Though the roots of modernity in Bangladesh (in architecture) goes back to early 1950s, with Muzharul Islam designing the Art College, and subsequently to be followed by the Dhaka University Library, NIPA Building, and the Science Laboratory, Chittagong University and the Jahangirnagar University. Even within BUET campus, we had our own building designed by Vrooman, and there were the gymnasium and the new student's halls by Bouigh (who took the name of Golam Rab as becoming Muslim, and also designed the Kamalapur Railway Station, Notre Dame College Brothers Hostel, and St. Joseph School). At a stone's throw distance was the Dhaka University TSC designed by Doxiades, which we used to frequently visit to play table tennis and swim afterwards in not so pleasant water of the pool.

Doxiades was a Greek architect-planner, who ran an organization named Ekistics in Athens, gave birth to such terms as 'mega polis', and did few town planning exercises in the developing countries of Africa and Asia, like Iraq and Pakistan, in the 1960s.

He also designed the Home Economics College, Comilla Rural Academy, NAEM Mosque behind Dhaka College, etc. There was a small Greek community in Dhaka along with the Armenians who were larger in number. They were mostly in business, and did many philanthropic works, including setting up schools and running newspapers. There probably is no Greek (settler) left in Dhaka now, while only one Armenian is looking after a 1781 church and the cemetery in Armanitola. Coincidentally, the TSC complex has a small Greek mausoleum, which possibly thanks to Doxiades didn't get demolished while building the modern complex.

The TSC Complex was an example of modern architecture that also respected the local culture and indigenous spatial arrangement around a court. The most memorable place in the complex for me was the corridor from underneath the lofty front building lobby till the cafeteria with a green lawn to the east! It also contains two small Siva Temples inside the Swimming Pool enclave, which were also retained. While to our horror we witnessed the demolition of a temple right in front of the National Museum building that could easily be preserved and perhaps used as a gatehouse to an institution that was supposed to be the custodian of our traditional architecture the Department of Archaeology and Museums (later split into two separate Departments)!!

Dhaka University campus had many other beautiful old architecture that I shall discuss elsewhere. But these wonderful architectures, both modern and traditional, had little impact on what we were learning. Instead of searching for roots in our own soil, the more so called enlightened ones were looking into post-modern trend as a means for reviving the classical elements, classical as we were taught since in the curricula made by the Texas A&M University we had Greek, Roman and European architecture, not Bengal. The Sangshad Bhaban was just completed, but nobody dared to say anything about it, and in fact didn't know how to learn the building, and unlearn whatever was already learnt. Dhaka University campus had many other beautiful old architecture that I shall discuss elsewhere. But these wonderful architectures, both modern and traditional, had little impact on what we were learning. Instead of searching for roots in our own soil, the more so called enlightened ones were looking into post-modern trend as a means for reviving the classical elements, classical as we were taught since in the curricula made by the Texas A&M University we had Greek, Roman and European architecture, not Bengal. The Sangshad Bhaban was just completed, but nobody dared to say anything about it, and in fact didn't know how to learn the building, and unlearn whatever was already learnt.

Sangshad Bhavan was designed by the world renowned architect Luis I Kahn. Kahn taught at the University of Pennsylvania most of his life which would design curricula to start architecture education in East Pakistan in the late-1950s. A School of Architecture was supposed to be start in a place south of the Art College which was later given away to bury National Poet Kazi Nazrul. Instead architecture program started with the Engineering University in 1962 as it was being converted to a University (from the Ahsanullah College of Engineering) and required a second faculty other than engineering to be regarded so. How wonderful it could be if architecture education started near the first true modern building in Bangladesh which has transcended ages!

It was the time, early 1980s, that the new generation Bangladeshi architects were daring to break the barrier. They turned to brick, brick not as a building element but as a space maker. Though before them brick architecture has been built, by Shahidullah for Agriculture Department, by Sthapati Sangshad for Health Department, or by Bashirul Haque for the Ispahanis, but hasn't been noticed by the academics.

Some of them gathered around Muzharul Islam; the sexagenarian young man told them to look into the soil to find authenticity!

Much earlier I learnt that Dhaka was a 'City of Mosque'. Traveling foreigners gave this title, not possibly because the city was full of mosques. I have lived in and traveled all over the Middle East. Possibly they have more mosques on average in a neighborhood or per person. I think as mosques were one of very few permanent buildings, built in mainly brick, and the rest in non-durable mud-thatch-reeds, these were dominating the skyline unlike today (so should we call Dhaka a city of apartments, a city of rickshaws, a city of beggars, or something else).

Binat Bibi mosque in Narinda, described as Narindim by the European voyagers, is the oldest surviving structure in Dhaka city. This Sultanate mosque was built in 1457 in memory of Bakht Binat daughter of a Turkish trader Marhamat (hence it is not 600 years old as many recent DS reporters claimed); the stone inscription in Farsi (Persian) is located on her grave at its north. Octagonal turret, hemispherical domes atop a square room, arches on south, north and eastern sides, modest ornamentation, plaster coating and curved cornices are the original features of the mosque. Unfortunately, not an enlisted structure, the mosque has seen three extensions to date. A dome was built atop a single room about 80 years ago. Next, a 2-storey building was built beside it some 20 years ago. Later a 4-storey building started to crop up covering the two domes, which however were dismantled due to pressure from concerned bodies.

In 2006 the Mosque Committee undertook an extension of the prayer area and a multi-storied madrashah in the compound, and started to demolish the original mosque to accommodate a 7-storey high minaret. Historically minaret is not a significant element in local mosque architecture, it indeed is a new feature introduced less than a century ago; hence its addition would distort the original design. A wall of the mosque was already knocked down and piling started when concerned academics and environmental activists intervened. Architecture students of the Asia Pacific University presented alternative solutions to the Committee which did not require destroying the heritage structure. The Committee eventually agreed to do necessary extensions without destroying the original structure. Last week I talked to the group only to learn that it was in fact dearth of fund and then Ramadan that stopped the demolition then, like in many other cases where poverty has been the blessing!

Now such intervention is both common and rare. The part that we are oblivious of our architectural heritage, and consider destroying and building new as part of development, is common. That building owners and users would eventually concede to the idea that architectural heritage should be preserved for the posterity, as Mahatma Gandhi said, we are only custodian of something which belongs to the future (generations), is rare.

I tried to intervene in similar cases before, but failed.

In December 1994, I took a group of 60 BUET students in their final year to Bogra, a city near two archaeological sites which are evidences of more than 2000 years of urbanization in this part of the world. The North Bengal city is a repertoire of ancient archeological relics and architectural heritage, vernacular architecture and contemporary works of foreign architects and local masters. The students visited the archeological remains of Mahasthan Garh dating back to the second century BC. They were impressed at the ruins on Nagri river that speak aloud of the society and culture of the past. In Sompura Vihara in Paharpur near Joypurhat, the students marveled at the largest Buddhist Monastery south of the Himalayas that expressed the high order of architecture that existed in the area one and half millennium ago. In December 1994, I took a group of 60 BUET students in their final year to Bogra, a city near two archaeological sites which are evidences of more than 2000 years of urbanization in this part of the world. The North Bengal city is a repertoire of ancient archeological relics and architectural heritage, vernacular architecture and contemporary works of foreign architects and local masters. The students visited the archeological remains of Mahasthan Garh dating back to the second century BC. They were impressed at the ruins on Nagri river that speak aloud of the society and culture of the past. In Sompura Vihara in Paharpur near Joypurhat, the students marveled at the largest Buddhist Monastery south of the Himalayas that expressed the high order of architecture that existed in the area one and half millennium ago.

The group went to see the works of architect Muzharul Islam at the Bogra Polytechnic Institute (done along with the famous American architect Stanley Tigerman). Their exposure to these works gave them a sense of modern architecture and its future direction in Bangladesh. On their way back they stopped at Sherpur, a small town known for its link with Shershah and several Mughal edifices. There they saw among others the beautiful Kherua mosque in early Mughal style. Without doubt the most illuminating for a splinter group of students however was the visit to Eruilbazaar to see, learn and document the timeless way of building mud houses in North Bengal.

They brought back from this visit a wholesome experience of the architectural heritage, and the wisdom of the past in evolving man's built environment and as well as modern concepts of form making and spatial articulation! Some 14 year later I followed the same trail taking along my students from the North South Architecture School which one of them wrote about in February this year in Campus.

During the first trip we spotted an ornately designed colonial period structure in the court area used by the Sonali Bank which was already partly demolished as there was a construction going on behind it. The rest was waiting for destruction once the furniture could be shifted to the new 8-storied under-construction building. We wrote to the Chairman of the Bank, and eventually got a call from the GM who took us to the MD who coincidentally happened to be from the same locality (of Bogra). The GM cautioned us how difficult it would be. Yet we could convince the MD to wait for couple of weeks so that a group of young BUET faculty could come up with an architectural solution that could integrate the old structure into the new one. We worked hard, laid papers and pencils on the meeting room fondly named after Vrooman, the father of architecture education in Bangladesh, made some quick design proposals; but the Bank was not returning our calls. Eventually to our dismay about a month later we learnt that the Bank Engineer had the building completely demolished the very next day we met the MD!!! During the first trip we spotted an ornately designed colonial period structure in the court area used by the Sonali Bank which was already partly demolished as there was a construction going on behind it. The rest was waiting for destruction once the furniture could be shifted to the new 8-storied under-construction building. We wrote to the Chairman of the Bank, and eventually got a call from the GM who took us to the MD who coincidentally happened to be from the same locality (of Bogra). The GM cautioned us how difficult it would be. Yet we could convince the MD to wait for couple of weeks so that a group of young BUET faculty could come up with an architectural solution that could integrate the old structure into the new one. We worked hard, laid papers and pencils on the meeting room fondly named after Vrooman, the father of architecture education in Bangladesh, made some quick design proposals; but the Bank was not returning our calls. Eventually to our dismay about a month later we learnt that the Bank Engineer had the building completely demolished the very next day we met the MD!!!

In November, 2006, I took an American Professor to a walk through the winding streets and mesmerizing quarters of old Dhaka. I was in fact following a route that I developed in the mid-1990s as a part of a Ford Foundation sponsored project at BUET, when I was taking groups of tourists, most often foreigners (our contact point was Samarkhand a coffee joint behind the Gulshan Azad mosque), to a Heritage Walk, possibly the first of its kind in Bangladesh, in old Dhaka. The group used to gather near the Bahadur Shah park, named after the last Mughal emperor who assumed the leadership of the first real pan-Indian rebellion against the British colonizers in 1857. The monument there was erected in 1963 by the DIT to commemorate the centenary of that Sepoy Revolution. Deposed Bahadur Shah breathed his last in Yangoon; I did visit his dargah in 2002 there.

Early Friday we would start at the St. Thomas Church, amble through Lakhsmibazaar and Jaluanagar, Sutrapur and Farashganj, that would take us two hours. The more enthusiasts would take a boat ride from the feet of Lalkuthi, disembark at the Wiseghat in front of the Bulbul Academy, see the Ahsan Manjil from the east gate, cross through the Sankharibazaar, stop here and there to look into the musical instruments, bangles, or stone engraving, and end at the Jagannath University (then a college) premises in another two hours time. Early Friday we would start at the St. Thomas Church, amble through Lakhsmibazaar and Jaluanagar, Sutrapur and Farashganj, that would take us two hours. The more enthusiasts would take a boat ride from the feet of Lalkuthi, disembark at the Wiseghat in front of the Bulbul Academy, see the Ahsan Manjil from the east gate, cross through the Sankharibazaar, stop here and there to look into the musical instruments, bangles, or stone engraving, and end at the Jagannath University (then a college) premises in another two hours time.

This time too, our last stop was Jagannath University where we found that the 160 years old Library Building, which once housed a very early Bank of Bengal, was under the hammers of demolishers to make way for a 20-storied commercial cum academic building. All precious and rare plants in an oval-shaped herbarium in the front were also uprooted. Immediately I contacted the media, and conservation and environment activists, returned to the spot twice on the day, talked to the students and the consultant, some of us went to the Kotwali to have it stopped. Eventually chased out of the campus by goons, we came to Daily Star. The media gave a good support. Few days later the VC met us to promise immediate suspension of the work and working through his various committees to adopt an alternative solution to their needs. Two days later we heard from the locals that number of workers was increased the same night immediately after our meeting to bring down the entire building to ground within a day.

We didn't have the heart to go again and see the barren ground!!

So who is the custodian of our cultural patrimony? I was asked by a colleague of mine last week.

It is us of course! It is us of course!

But then the government gave the stewardship to the Department of Archaeology, who more often tends to forget that they are only given the responsibility to properly look after some treasures that belongs to us, not to them! And they think that they really need to possess the structure in order to protect them!! This is the reason why the most magnificent palatial mansion of Dhaka, the Ahsan Manjil, though preserved, is not a Listed Building, i.e. not protected by the law!!!

What they really do in terms of protection is mounting a blue board declaring that it is illegal to deface the structure. But that is not enough to deter the vandals, abusers and illegal occupiers of the heritage structures.

The same faculty told me that the so called illegal occupiers of the Bara Katra were in fact paying regular rent to the Archaeology Department! So who was the abuser? That the Department couldn't care less is evident from their official webpage. You click the Antiquities Act, and find that it says it is applicable to whole of Pakistan!

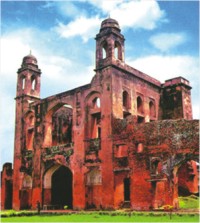

Katra is a form of dormitory building built around an oblong courtyard; the form originated in Northern India or Persia, the home of some of the rulers, members of the royal court and the nobility. However, the term may have been derived from Arabic katara which means colonnaded building. Situated on the south of Chawkbazaar and near river Buriganga, Bara Katra was one of the most beautiful Mughal buildings in Dhaka. Meer-e-Imarat (Chief Architect) Abul Quasem was assigned by Subehdar Shah Suja to build a Palace, which after completion was given to Quasem as Suja did not like it. Built in 1644, it was used as an inn whose expenses were borne by the rents from 22 integrated shops. The quadrangular building had rooms around an open court with gates in the north and south. The 223' wide river side façade has a 3-storey high gatehouse in the middle with two octagonal turrets at two ends.

Since the shifting of capital (first the Treasury to Murshidabad in 1704, and eventually the capital in 1713) the Katra started to loose its importance, though the Naib-Nazim (Deputy Governor) Jisarat Khan briefly stayed here before his palace (in Nimtali) was built in 1765 under the supervision of Lt. Swinton (Sultan Shaheb). 1822 accounts by D'Oyle testify to the beauty of the structure partly surviving then, plundered by the poor inhabitants. Attempts by the Archaeology Department in the past to take over the structure and restore it to its original glory have been unsuccessful.

Chota Katra, a relatively smaller one, was close to the East of Bara Katra, built between 1663-71 by Shaista Khan, the most successful and powerful Subehdar of Bengal and a prolific builder. This is the Subehdar who is credited with bringing down the price of rice to an incredibly low, and also introduce an architectural style referred to as the Shaista Khani style.

The British made some additions to the Chota Katra, once used by the first Normal School in Dhaka (c1816), and the Nawabs as a coal and lime godown. The 1-dome Mausoleum of Bibi Champa, a listed building now, was within its compound which was completely destroyed by a priest.

Besides these two Katras, there were several more such rectangular cellular structures mainly used as inns or residencial enclaves, for example Muqim Katra, Nawab Katra, etc. We do not find any reminiscence of Mughal period built residential quarters in Dhaka or elsewhere in Bengal, except these few (katras). Though architecture students in their newly found enthusiasm in last quarter of a century have made many design proposals following the morphology an oblong courtyard enclosed by cells, very few buildings have actually been built in the design. Besides these two Katras, there were several more such rectangular cellular structures mainly used as inns or residencial enclaves, for example Muqim Katra, Nawab Katra, etc. We do not find any reminiscence of Mughal period built residential quarters in Dhaka or elsewhere in Bengal, except these few (katras). Though architecture students in their newly found enthusiasm in last quarter of a century have made many design proposals following the morphology an oblong courtyard enclosed by cells, very few buildings have actually been built in the design.

Courtyard in right size and location brings a design down to earth. It makes feel the space, tie the space. Courtyard is a congruent space, courtyard is a soothing space, courtyard is a multi-purpose space. In fact courtyard is a universal space. This is found in almost every culture, but in different manifestations, from China to Mexico, Hausa to Prussia.

We also see courtyards or sahn surrounded by colonnades in many mosques, but hardly in any mosque in Dhaka; the Gausul Azam (Iraqi) mosque in Mahakhali is a good exception. Though we may study mosque architecture, the components of a typical classical mosque, but hardly design any mosque as academic exercise. In reality many mosques are designed by architects, but not as a spiritual place where you connect with the almighty above. And contemporary architects tend to break the established forms, and try to invent new (deformed) elements which have no reference in history!

Golap Shah masjid is an example. It was first built on the island in front of where it is now, at the corner of the Osmani Udyan. The island (road median) was required to be narrowed, and hence the mosque removed to a temporary form built with bent aramit sheets. It was situated next to Mahanagar Pathagar, a railway bungalow from the 1950s, which instead of demolishing like its several other neighbors, the government Department of Architecture decided to have restored and adapt as a library to link old Dhaka with the new. However, few years back, without anybody's notice, the library building was demolishing to make way for an enlargement of the mosque.

However none could possibly match in size and importance the national mosque of Baitul Mukarram, conceived as a Qaba-like cube. Designed like many of its contemporary buildings by Thariani, a firm established by a diploma engineer from West Pakistan who because of his good connections with mainly Urdu speaking moneyed businessmen and industrialists had a monopoly over the profession of architecture in the 1960s. Though the company had a chance of designing hundreds of buildings, it couldn't utilize the scope to develop an indigenous architectural style. It is also said that this mosque was put there to stop some properties to its north owned by Mr. Thariani's other clients from being acquired to extend the major axis road connecting the old Dhaka with the new. Another mosque with its flat canopy roof was recently conceived and built in one of the Bashundhara group's factory site. This won an award from India. One moderate size mosques that tried to integrate all the spiritual, spatial, and symbolic elements of a traditional mosque is that of the Bakshibazaar mosque of the BUET east campus. With a central barrel vault, Jatiyo Smriti Shoudha mosque in Savar would be no less interesting.

However, mosque has also been used to establish possession over land, even if by creating problems for the people. One best example is the Sobhanbag mosque.

(Writer is a Professor of Architecture, North South University)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |