Feature

An Architect's Dhaka

Dr. Mahbubur Rahman

Part Twelve

|

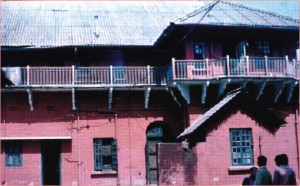

Chummery House in the 1970s before restoration |

THERE is no government policy as such on architectural heritage conservation in Bangladesh hardly any specified methodology or procedure has been followed by the government or any other organisation. An Antiquities Act was enacted in Pakistan in 1968 following a similar one in other sub-continental countries; it was further amended in 1976. The Department of Archaeology usually carries out architectural restoration in the country. The Department of Architecture under the Ministry of Public Works too undertook several significant architectural conservation projects, though not as part of a consistent policy, rather out of personal decisions and methods adopted by the architects and other professionals engaged in the process.

The Indian Conservation Manual prepared by John Marshall in 1922 for the newly introduced archaeological works in British India is followed in Bangladesh, as well as in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Marshall laid down the broad principles for the repair and preservation of monuments. However, it caters mainly for archaeological conservation that is different from architectural conservation. Yet due to the absence of knowledge many often view archaeological conservation same as architectural conservation, leading to resentment among different professionals and agencies, overlap, contest, and jealousy regarding jurisdiction, adopting wrong methods or involving amateurs. These led into indifference and blatant ignorance, and hence more incidents of destruction/defacing than preservation occurred.

Many countries have manuals of their own taking into cognisance of their specific context and constraints. Due to an introduction of related academic studies about a decade ago and access to internet, some useful and supporting literatures have only recently become easily accessible. That developed by INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) for India could be followed in Bangladesh until it develops, adopts and makes use of its own manual. Of particular interest in this context would be the development of a National Conservation Policy that could put the issues into broader context of government's socio-economic and cultural goals and developments, and define its stand in this regard.

INTACH was set up in 1984 in Delhi to protect and conserve cultural heritage of India. The pioneer of heritage conservation there has 117 chapters comprising more than 2 million enthusiastic members all over the country. INTACH strives to spread heritage awareness among public; protect and conserve India's heritage; document cultural resources; and train and develop skills and related professions. Its objectives are to sensitise the public about India's pluralistic cultural legacy; instil a sense of social responsibility towards preserving its common heritage; protect and conserve the natural, built, and living heritage; document unprotected buildings of archaeological, architectural, historical, and aesthetic significance and cultural resources; develop heritage policy and regulations; and intervenes to protect heritage.

In the past, the government's architecture office did undertake some important conservation projects that included the conservation of the Collectorate Building in Jessore, the Ahsan Manjil, the Old High Court Building, the Chummery House and the Mahanagar Pathagar in Dhaka. I have already written about the Ahsan Manjil and other buildings in Dhaka owned by the Nawabs; today I shall briefly present another restoration project done by the Department.

Chummeries have been built all over British India to house the bachelor officers of its civil administration. The two storied cottage type building opposite the present National Eidgah gate was built in 1920 in a late Georgian vernacular style.

At that time it was in the middle of several extensive and elaborate gardens stretching from current Toyenbee Circular Road in the east to Sonargaon Janapad/Penetrator Road to the west, and from Paribag to Nimtali in north-south. A major part of it was developed during the early-Mughals as Bag-i-Padshahi out-of-town large gardens in part of Sujatpur and Chistia mahallas. The area repeatedly fell into decay from negligence as their patrons either left the city or became financially weakened, and was gradually encroached by marshes and jungles.

Magistrate Daws in the 1820s started to regenerate the beauty of the area by clearing the swamps and creating various recreational grounds mainly for the Europeans with the help of the jail convicts. The Chummery fittingly looked over a cricket ground to its west; further west of which was created the race course eventually taken over by the Nawabs, who also established a zoo to its north. To its east in Paltan and Topkhana, separated from the Nawab Ahsanullah's garden in Dilkhoosa by water bodies, was the cantonment and ordnance depot till early last century. So the Chummery was like a club where both colonial civil and military officers could mingle. It reciprocated the Gymkhana Club on the other side of the oval, and anybody could imagine the amount of fanfare, cheers, clapping and excitement accompanying horse racing, polo, cricket, croquet or golf part of the colonial culture.

|

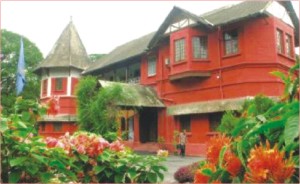

Chummery in the 1990s after restoration |

However, after the end of British rule in the sub-continent, the building saw different uses ranging from the government officers bungalow, part of Salimullah Muslim Hall, Dhaka University Girls' Hostel, to headquarters of the Public Service Commission. It has been known as the CIRDAP House since 1985 when it was handed over to the Centre for Integrated Rural Development of Asia and the Pacific. However, it is more popularly known as the 'Chameli' house after a flower in colloquial language, as for many years till the early-1980s the official signboard showed the name as such! Many people were even not aware that Chummery and another popular Bengali word 'Chumcha' have the same origin chum or close friend.

The conservation of the Chummery House, completed in 1985, gave careful attention to restoring the building's original appearance. The walls used mud and lime mortar; the exposed walls were coloured red. Except the wooden shingles on the sloped and conical roofs that proved too expensive and short-lived for the local climate, almost every other detail of the older building was judiciously renovated/reconstructed. The corrugated iron roof of later period was replaced with specially made ash-coloured asbestos tiles mimicking the appearance of the original wooden shingles. The internal partition walls erected over the years were mostly removed.

There were few other buildings in its vicinity that deserved conservation; some of them had earlier been destroyed, for example the bungalow where Satyen Bose used to live, to make way for the new Press Club building and auditorium, a project for which I made my first professional model while I was in my second year of architecture study. Incidentally the next project of which I was making a model was the Dhaka Shishu Park, which too brought down some old dilapidated structures around its west boundary, and we were not aware of any of these.

In fact a recent project to erect a highrise building to the south of Chummery House raised controversy as historians and conservationists showed concerns, who nevertheless were silent when some other not-so-good-looking buildings were erected nearby at different times threatening the visual and spatial integrity of the area. The building to its north across the street that is used as the Foreign Ministry's office was built as the Ramna House, which too for sometime in the late-1920s was used to accommodate the Muslim students of Dhaka University, who couldn't be accommodated at the hostel set up on the upper floor of the Secretariat Building that then was being used as the Arts Faculty Building (current Dhaka Medical College Hospital).

The Chummery in fact was part of a large number of bungalows built in Ramna between Nilkhet and Fulbaria (Fulgari), which after the annulment (of the partition of Bengal) in 1911 were mostly given away to attract professors for the Dhaka University. These were all taken over by the provincial government for its ministers and secretaries after 1947. Known by numbers, some of these bungalows still exist, for example the Chief Justice house was the Commissioners office; the Collector's office was behind that which to some extent resembled the Chummery.

(Professor of Architecture, NSU)

|