| Spotlight

Emily Dickinson Emily Dickinson

Brief Biography

Compiled by Star Campus Desk

EMILY ELIZABETH DICKINSON (December 10, 1830 May 15, 1886) was an American poet. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, to a successful family with strong community ties, she lived a mostly introverted and reclusive life. After she studied at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she spent a short time at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's house in Amherst. Thought of as an eccentric by the locals, she became known for her penchant for white clothing and her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, even leave her room. Most of her friendships were therefore carried out by correspondence.

Although Dickinson was a prolific private poet, fewer than a dozen of her nearly eighteen hundred poems were published during her lifetime. The work that was published during her lifetime was usually altered significantly by the publishers to fit the conventional poetic rules of the time. Dickinson's poems are unique for the era in which she wrote; they contain short lines, typically lack titles, and often use slant rhyme as well as unconventional capitalization and punctuation. Many of her poems deal with themes of death and immortality, two recurring topics in letters to her friends.

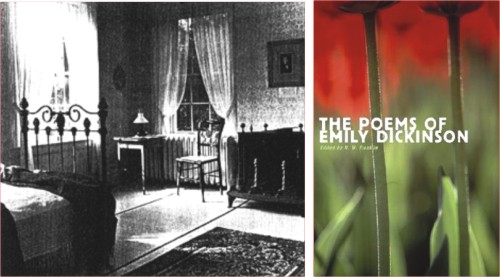

Although most of her acquaintances were probably aware of Dickinson's writing, it was not until after her death in 1886when Lavinia, Emily's younger sister, discovered her cache of poemsthat the breadth of Dickinson's work became apparent. Her first collection of poetry was published in 1890 by personal acquaintances Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd. A complete and mostly unaltered collection of her poetry became available for the first time in 1955 when The Poems of Emily Dickinson was published by scholar Thomas H. Johnson. Despite unfavorable reviews and skepticism of her literary prowess during the late 19th and early 20th century, critics now consider Dickinson to be a major American poet.

Early influences and writing

When she was eighteen, Dickinson's family befriended a young attorney by the name of Benjamin Franklin Newton. According to a letter written by Dickinson after Newton's death, he had been "with my Father two years, before going to Worcester in pursuing his studies, and was much in our family." Although their relationship was probably not romantic, Newton was a formative influence and would become the second in a series of older men (after Humphrey) that Dickinson referred to, variously, as her tutor, preceptor or master.

Newton likely introduced her to the writings of William Wordsworth, and his gift to her of Ralph Waldo Emerson's first book of collected poems had a liberating effect. She wrote later that he, "whose name my Father's Law Student taught me, has touched the secret Spring". Newton held her in high regard, believing in and recognising her as a poet. When he was dying of tuberculosis, he wrote to her, saying that he would like to live until she achieved the greatness he foresaw. Biographers believe that Dickinson's statement of 1862"When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality but venturing too near, himself he never returned"refers to Newton.

She was probably influenced by Lydia Maria Child's Letters from New York, another gift from Newton (after reading it, she enthused "This then is a book! And there are more of them!"). Her brother smuggled a copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Kavanagh into the house for her (because her father might disapprove) and a friend lent her Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre in late 1849. Jane Eyre's influence cannot be measured, but when Dickinson acquired her first and only dog, a Newfoundland, she named him "Carlo" after the character St. John Rivers' dog. William Shakespeare was also a potent influence in her life. Referring to his plays, she wrote to one friend "Why clasp any hand but this?" and to another, "Why is any other book needed?"

Adulthood and seclusion

In early 1850 Dickinson wrote that "Amherst is alive with fun this winter ... Oh, a very great town this is!" Her high spirits soon turned to melancholy after another death. The Amherst Academy principal, Leonard Humphrey, died suddenly of "brain congestion" at age 25. Two years after his death, she revealed to her friend Abiah Root the extent of her depression: "... some of my friends are gone, and some of my friends are sleeping sleeping the churchyard sleep the hour of evening is sad it was once my study hour my master has gone to rest, and the open leaf of the book, and the scholar at school alone, make the tears come, and I cannot brush them away; I would not if I could, for they are the only tribute I can pay the departed Humphrey".

During the 1850s, Emily's strongest and most affectionate relationship was with Susan Gilbert. Emily eventually sent her over three hundred letters, more than to any other correspondent, over the course of their friendship. Her missives typically dealt with demands for Sue's affection and the fear of unrequited admiration, but because Sue was often aloof and disagreeable, Emily was continually hurt by what was mostly a tempestuous friendship. Sue was nevertheless supportive of the poet, playing the role of "most beloved friend, influence, muse, and adviser whose editorial suggestions Dickinson sometimes followed, Susan played a primary role in Emily's creative processes." Sue married Austin in 1856 after a four-year courtship, although their marriage was not a happy one. Edward Dickinson built a house for him and Sue called the Evergreens, which stood on the west side of the Homestead.

Until 1855, Dickinson had not strayed far from Amherst. That spring, accompanied by her mother and sister, she took one of her longest and farthest trips away from home. First, they spent three weeks in Washington, where her father was representing Massachusetts in Congress. Then they went to Philadelphia for two weeks to visit family. As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson's domestic responsibilities weighed heavier upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Lavinia stated that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Emily took this role as her own, and "finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it".

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Emily began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, she began making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books. The forty fascicles she created from 1858 through 1865 eventually held nearly eight hundred poems. No one was aware of the existence of these books until after her death.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican, and his wife, Mary. They visited the Dickinsons regularly for years to come. During this time Emily sent him over three dozen letters and nearly fifty poems. Their friendship brought out some of her most intense writing and Bowles published a few of her poems in his journal. It was from 1858 to 1861 that Dickinson is believed to have written a trio of letters that have been called "The Master Letters". These three letters, drafted to an unknown man simply referred to as "Master", continue to be the subject of speculation and contention amongst scholars.

The first half of the 1860s, after she had largely withdrawn from social life, proved to be Dickinson's most productive writing period. In direct opposition to the immense productivity that she displayed in the early 1860s, Dickinson wrote fewer poems in 1866.

Emily Dickinson

A Prolific Private Poet

"When a little girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality but venturing too near, himself he never returned"

--- Emily Dickinson

May 15 was the death anniversary of one of the leading American poets Emily Dickinson. Students of English literature and connoisseurs of English poetry read Dickinson with avid interest and passion. To pay tribute to this great poet Star Campus has requested Syed Badrul Ahsan and Prof. Mohit Ul Alam to discuss some aspects of her works.

Emily Dickinson . . . in soul, in ecstasy

Syed Badrul Ahsan

THE mind is wider than the sky. That was the way Emily Dickinson looked at the world outside her. Or you could say it was the way the soul worked in her. Weigh that statement. There is something of the metaphysical about it. There is a linkage of ideas which comes into a working out of the imagery. Consider the universe you are part of. Or think of yourself, the essential you in whom the universe comes to epitomize itself. That is what comes through in Dickinson, in her use of words, the words shaping a thought, the thought leading you on to a wider ambience of experience. That is how Dickinson's poetry comes to us. It is different from the way we have perceived poetry through the ages. The different emanates from the fundamentally reclusive which Dickinson has personified, indeed held up as a model for herself in her lifetime. It is also in the mode she employed in her poetry, in the sense that the poems did not have titles, indeed the formulation of her verses employed such grammatically unconventional forms as the use of unexpected capital letters where small letters would have sufficed. But that, you will likely argue, is liberty poets are perfectly within their rights to take advantage of. Dickinson did it, in all her eighteen hundred or so poems composed over a creative lifetime spent in fashioning ideas.

Was Emily Dickinson drawn to conventional faith? The answer to this kind of query comes in a rather simplistic manner. Like men and women of her generation, she comprehended the place of religion in life. And yet there was, once she had outgrown youth and was well into deeper communion with the world around her, the feeling in her that faith was not merely to be discovered through a conventional observance of its basic tenets. It was also to be spotted in the beating of the heart. People went to church, thought Dickinson, to find God. For herself, God was in the heart, right in her home. She did not wear her faith on her sleeve. She simply felt it in all her consciousness.

And that was the way things were in her native Amherst, Massachusetts. It was New England ambience that mattered. In the early to late nineteenth century, it was intellectual liberalism which underscored the pursuit of education, of anything, in Massachusetts. At Amherst Academy and then at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, Dickinson was part of the air of academic freedom New England then symbolized. And yet there was something more, something greater in terms of desire that tugged at her heart. It was always home that beckoned her. She kept going back home, eventually making it a point not to leave it again. Amherst provided the perfect backdrop to a flowering of her poetic genius. It came in association with her aloofness, with her isolation if you will, from her surroundings. She was forever uneasy dealing with people or making small conversation. In her aloneness, though, she was endlessly in conversation with herself.

The conversation was with her poetry. Or conversation for her was poetry. Think back on the profundity of the thoughts in the poem beginning thus:

Safe in their alabaster chambers / untouched by morning and untouched by noon / sleep the meek members of the resurrection / rafter of satin, and roof of stone. Light / laughs the breeze in her castle of sunshine / babbles the bee in a stolid ear . . .

There is certainly a quality of the arcane about the poem and you wonder at the deep religiosity which pervades it. She speaks of death. Mortality was always a poetic preoccupation with her, the underpinning of which happens to be this poem. Alabaster is symbolic of beauty; and it is cold. Death, if you must know, is a cold affair. But then there is the matter of the resurrection. How do those expected to resurrect themselves lie still in death?

In Emily Dickinson, you run into a panoply of thoughts, perhaps of the kind you stumble into in modern poets. Difficulty of understanding is what you experience, all the while knowing that the difficulty is compounded by the poet's own questions about the mystery of life and death, of the process of Creation itself. Reflect on the following:

The murmur of a bee / a witchcraft yieldeth me / If any ask me why / 'twere easier to die / than tell / the red upon the hill /taketh away my will / if anybody sneer / take care, for God is here / that's all.

A romantic spirit was what Emily Dickinson was constituted of. The lyrical came in beautiful tandem with the spiritual in the poems and, doing so, lifted the poetry to heights rare in the annals of literature. Feel the throbbing sense of life and death, of beginning and end, in these thoughts:

If I should die / and you should live / And time should gurgle on / and morn should beam / and noon should burn / as it has usual done . . . / it make the parting tranquil / and keeps the soul serene . . .

The soul, said Dickinson in one of her usual reflective moments, should always stand ajar, ready to welcome the ecstatic experience.

It is ecstasy you dip into and stay in . . . as you take in the warmth of Emily Dickinson's poetry.

(Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor, Star Literature and Star Books Review)

Negotiating Emily Dickinson Negotiating Emily Dickinson

Mohit Ul Alam

MORE often than not good poetry inheres in difficulty. Negotiating John Donne's poems in the seventeenth century was an upheaval task, and an annoyed John Dryden said they (Donne and his group of metaphysical poets) 'affect metaphysics' too much. In the nineteenth century G. M. Hopkins created bubbles with his poetry written in a fashion called the 'sprung rhythm'. Of his many wonderful poems though, this line from “The Windhover” never disappears from my memory: “My heart in hiding / Stirred for a bird, / The achieve of, the mastery of the thing!” Another problematic poet in the last century was W. H. Auden, but again whose poems will be etched in our memory for their extraordinarily brilliant images.

In one poem, he refers to the lines formed on the forehead of a man with the railway tracks encountered at a railway junction, and in another poem the moment of arrival in a hotel lobby by a boarder is described as a warm hug with which an overcoat engulfs a wearer on a wintry night.

Difficult poets, however, show magic and so does Dickinson, whom also I would like to group with the poets considerably difficult. As a reader of poems, my personal penchant is to read poems that sensitize me with the thought of imagery released in clear meanings. Dickinson of course is not of that type of poets. That's why we have to negotiate her poetry.

In The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Vol. 1 (Third Edition) Dickinson has 66 poems included, all short-sized, not a single one going beyond the half-page. Actually Dickinson always wrote shorter poems, like broken monologues, in the fashion of diary entries. The poems are numbered without titles. In The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Vol. 1 (Third Edition) Dickinson has 66 poems included, all short-sized, not a single one going beyond the half-page. Actually Dickinson always wrote shorter poems, like broken monologues, in the fashion of diary entries. The poems are numbered without titles.

In some poems, I notice proverbial utterances, good poetry but gilded with an aphoristic tone: “Success is counted sweetest / By those who ne'er succeed.” This saying can be 'contexualised' in Dickinson's own time when the Puritan ideal “earn your bread through your sweat” was compromised by Benjamin Franklin with a more cozy expression the success ethic which of course had a bitter side too, only awaiting to be exposed by Dickinson in such lines as this: “For each beloved hour / Sharp pittances of years--/ Bitter contested farthings--/ And Coffers heaped with Tears.”

Lo! Coffers heaped with tears! More money, more pain isn't it characterizing America? Or our own society, bridging the distance in time and space! A good poet has to be universal, and so is Dickinson.

But come to this short four-liner gem of a lyric: “'Faith' is a fine invention / When Gentleman can see / But Microscopes are prudent / In an Emergency.” The italics are hers, but look at the dare she obliquely makes at the probable 'invention' of religion by men, and this faith becomes embarrassingly inoperable in the face of death. In an emergency case in the clinic the microscope (in the modern sense, the third or fourth generation medical appliances and tools) is of greater help than faith.

Dickinson's major forte lies in those poems where broken phrases give out broken thoughts like sparks in a motor factory, though the summing up is left to the reader to do every which way he can: “Rowing in Eden--/ Ah, the Sea! / Might I but moor Tonight--/ In Thee.” May be a complete sense of merging with God?

Another poem has another basic dichotomy finely brought up. Keats in his famous “Ode on a Grecian Urn” gave the world this equally famous chiasmus: “Beauty is truth / Truth beauty.” For Keats the combination was a kind of solution for all human problems. But for Dickinson, following Keats by nearly half a century or so, it became easy to embed it with a sarcastic twist where beauty and truth are still a compatible pair, but not on this earth, rather into the tomb, because they both are buried off from this world: “He [Truth] questioned softly “Why I failed”? / “For beauty”, I [Beauty] replied--/ “And I for TruthThemselves are One / We Brethren, are”, He said--. Another poem has another basic dichotomy finely brought up. Keats in his famous “Ode on a Grecian Urn” gave the world this equally famous chiasmus: “Beauty is truth / Truth beauty.” For Keats the combination was a kind of solution for all human problems. But for Dickinson, following Keats by nearly half a century or so, it became easy to embed it with a sarcastic twist where beauty and truth are still a compatible pair, but not on this earth, rather into the tomb, because they both are buried off from this world: “He [Truth] questioned softly “Why I failed”? / “For beauty”, I [Beauty] replied--/ “And I for TruthThemselves are One / We Brethren, are”, He said--.

Her consciousness about a world beyond this world is graphically mysterious, or mysteriously graphic which is depicted in another not very short poem, where she begins with the assertion that “This world is not Conclusion,” and then continues her attempt to identify the phenomenon, which, she thinks, has the answer. But it's more evasive than ever, and the groping for it ends in frustration. Music, sound, philosophy, Crucifixion (“Faith slips”), laughs, rallies nothing can give shape to that mysterious feeling. Lastly, I would say, to part with Dickinson, I mean to leave reading her poetry, is to feel the way she describes parting: “Parting is all we know of heaven, / And all we need of hell.”

(Dr. Mohit Ul Alam is Professor and Head of English at ULAB)

|

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2010 |