Inside

|

Why did Durga, Sarbajaya, and Aparna have to die Rubaiyat Hossain ponders the disquieting dispensability of the female characters in the Apu Trilogy Satyajit Ray, making his first film in 1955, was to make a serious statement as a long-standing member of the Bengali intelligentsia on the type of "modernity" that was to be ushered in by the Indian nation state, especially in the context of rural Bengal. I would argue that the Apu Trilogy, made between 1955 and 1959, is Ray's first coherent narrative of the trajectory from tradition to modernity, from rural to urban, from darkness to light, from unreason to reason.

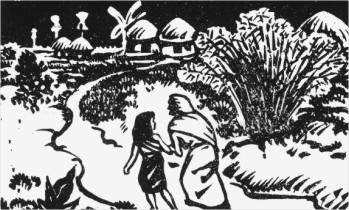

Critically understanding the woman's position within the nationalistic narrative can open up a unique view to interrogate the colonial past, and offer a clearer sense of the nationalistic politics. Lata Mani and Gayatri Spivak have noted the disappearance of the female figure from the patriarchal nationalistic narrative into a textual space where she is forever caught between "tradition" and "modernity," "patriarchy" and "imperialism," "subject-constitution" and "object-formation." As women literally become the discourse between "tradition" and "modernity" in colonial Bengal, it is important to examine various nationalistic narratives and observe how they handle the figure of the woman, and where she is placed in the discourse. I would like to trace Satyajit Ray's placement of the female figure in his narrative of "modernity" by primarily looking at Pather Panchali (1955), Aporajito (1956), and Apur Sangsar (1959). Satyajit Ray's cinematic representation of Apu peering through a torn blanket to carrying his son on his shoulder is the trajectory of Ray's modern man. The growth of this man is deeply influenced by the death of the female figures in his life -- his sister, his mother, and finally his wife. If we compare Ray's depiction of Apu's trajectory towards modernity, and Bibhutibhushan Banerjee's resolution of the Apu character in relation to the female characters in the novel, perhaps the nationalistic ambiguity in Ray's representation of women will become apparent. Banerjee's notion of modernity was vested in English education, scientific knowledge and in being able to relate the personal to the universal. Ray's Apu displays similar qualities, only, his freedom as an individual is far more liberating than Banerjee's narrative. Banerjee's narrative runs on the fuel of nostalgia which drives the story back to Nischindipur, whereas Ray's Apu seems to have little problem letting go of attachments, other than Aparna. Ray's Apu also surrenders to nature in the face of the tragedy, but emerges again as a responsible father carrying Kajol on his shoulders, and the viewers are left to ponder where this couple will end up. If Ray had made the decision to take the father and son back to Nischindipur it would have given the film a whole new closure, coming back to the starting point again almost like repeating a ritual, but Ray is far too modernist for it. Ray's modernist interpretation of the closure of the trilogy emphasizes the notion of human freedom, mobility, and progress -- however, the women still fall behind. A sharp contrast between Apu and Durga is created in Ray's Pather Panchali. Apu's instrumental waking up scene (Pather Panchali) is initiated by Durga. She gets him ready for school, and he is on his way to progress. Durga is the child closer to animals and Indir, whereas Apu is closer to the more important members of the family, Harihar and Sarbajaya. The death of an old widow from the narrative of modernity was witnessed by young Durga, a girl who is also a burden to the national progress. Durga's story is not one of freedom and glory, however, it is not questioned why, but answered by Apu's success. Apu makes the journey, that is why Durga does not. When the children go to watch the train it is Apu's perspective that is emphasized, not Durga's. In Ray's narrative Durga is linked to the natural and Apu to the modern. Apu, sitting down with his parents and his sister at night, strains his ears for the train's sound. When the train finally comes and he runs the overwhelming affect of speed is marvelous! Apu is related to the material, the velocity, the possibility of moving out of Harihar's failed masculinity and Indir, Durga, and Sarbajaya's inherently inadequate femininity. Durga dies right after wholeheartedly accepting the monsoon water, her final destiny of death comes after her surrender to nature, she almost dissolves into it. Apu, on the contrary, survives the rain, he also lives through his surrender to nature (reference to Apur Sansar). Durga's beating is observed by him, he knows her darkest secrets, and before leaving the village he throws the stolen necklace into the pond. The moss slowly closes up, thus closing the story of Durga the unwanted female child, as Apu sits on a bullock cart to ride on a train to Benaras. In Apur Sansar, Aparna is also equated with nature by Ray. Apu is taken out of the urban backdrop to a strikingly different backdrop of an East Bengal village for his unplanned wedding. He takes on the role of saving the bride from the original lunatic match, and we see him on his wedding night speaking to himself, speaking to his wife, moving through the scene, as Ray's mise en scene places Aparna on the far right corner of the screen calmly bowing her head. In Ray's narrative Aparna is a burden for the superstitious rural village, a woman whose death will be instrumental in diverting Apu to nature, thus pushing the narrative to a final resolution. Ray's natural antithesis to Western materialistic modernity depends on the death of the women in his films. Women, who represent nature, push Apu to his ultimate triumph of modernity. Ray creates a contrast between Aparna and Apu, which is again absent in the book. Aparna is bothered by the train noise, whereas it is almost a part of Apu's life. Aparna kills cockroaches and breaks coals for the breakfast fire while Apu obliviously plays his flute. When Apu attempts to get another job to afford a maid, Aparna is surprisingly calm, and says: "quit the tuition you have now, and my poor husband will come home to spend the evening with me." This romantic and self-sacrificing speech is not indigenous to Banerjee's book, but planted by Ray. When Aparna goes to the village her letter arrives in Calcutta. As Apu reads the letter Aparna's calm and sweet voice brings back the quaintness and melody of the rural natural village. Her voice is punctuated by urban interruptions, but when Apu starts reading it again the sense of bliss is re-established. When she dies Apu has to surrender to nature and give up his novel. Nature does not consume Apu as it did Aparna and Durga, but gives him back to life with the strength to carry on, and take responsibility of his son. In Ray's narrative Apu's surrender to nature is the natural antithesis to Western material modernity. Apu's mother Sarbajaya is not fully equated with nature because she is the material source for his higher education. It is with the money she earned as a maid in Benaras that Apu is able to go to school in Manshapota, and later go to Calcutta. His concern for his mother in the film is negligible, whereas in the book his concerns and his longing for her are emphasized. In the book Apu feels special pride in sending his mother ten taka by money order, whereas in the film Apu remains naïve about his mother's illness. While Apu is studying in Calcutta, Sarbajaya dies without any treatment or care. Apu does not react to his mother's death very seriously, furthermore he leaves without performing her last rites, thus cutting off the remaining tie with the rural. Sarbajaya's death implied the end of Apu's relationship with rural life. Sarbajaya's death sets him as a free man in Apur Sansar. Satyajit Ray uses women as a natural antithesis to Western material modernity. This antithesis pushes the subject towards an alternative modernity, where the woman's sufferings and exploitation are rendered transparent -- she is removed and forgotten. Banerjee's narrative constantly commemorates the dead females, whereas Ray's narrative eliminates them with complete closure. Banerjee is a far more emotional writer than Ray is as a film maker. Banerjee's Apu is rooted in nature, whereas Ray's Apu is rooted in the train, Banjeree's Apu displays more emotion, friendship with females, feminine qualities such as decorating the room and dressing up versus Ray's Apu who comes across as a free roaming man after Sarbajaya's death. Banerjee's Apu can never forget about Durga and Nischindipur, thus preserving a place for remembering the deceased females in modernist narrative of the novel. The last page of Banerjee's Pather Panchali reads: Suddenly Apu's heart filled with a curious emotion. It was not grief, nor was it loneliness. He did not know what it was. It was compounded of so many feelings, so many memories that flashed across his mind in a single moment of time: Auturi witch, the steps down to the river, the past under the chalta tree, Ranu, the games he played in the afternoon, the games he played at midday, Potu, Durga's face. And all the things she longed for and never got. And there she was still watching. Then the words of his heart found expression in tears, as time and time again he struggles to send her a message: "I am not really going away Didi…I haven't forgotten…it's not that I want to leave you…they're taking me away!" It was true. He had not forgotten, and he did not forget. It is this Apu of Bibhutibhusan who sheds tears for the defeated Mahabharat's hero Karna, it is the imaginative Apu who gets in trouble for collecting crow eggs believing one could fly with the help of vulture eggs filled with mercury. This Apu is not present in Ray's modernist interpretation of Banerjee's novel. Banerjee's sense of advuta, anada is established in Ray's trilogy, but the humble return to the rural land is not proposed. Ray worked very intricately on the train sequences, and made the train track a reoccurring object in Apu's houses in Aporajito and Apur Sansar. It can be concluded that Satyajit Ray's Apu moved hastily with the trains and left behind his unfortunate sister in the dead dark corner of Nischindipur. This road to modernity crushed the possibility for Durga's growth, moreover, deleted her memory from the narrative of modernity entirely. This disappearance is not accidental, but is aesthetically planned to cover up the Bengali modernist ambiguity in violating women's individuality. This violation is erased from the narrative to make India's transition from tradition to modernity unproblematic, homogenous, and gender neutral. The entering of the snake in the Nischindupur household, and Apu leaving Manshapota without performing his mother's last rites indicate the clear trajectory towards the urban. Pather Panchali, produced by the West Bengal government, had set the parameters for Ray to depict a clear trajectory to urban from rural. This trajectory is one-way, and the possibility of reverse migration to the village is sealed off by the curvilinear entrance of a snake into Harihar Ray's household. The latter films of the trilogy carefully design Apu's return to the natural, and raises him to the level of a denouncer of the material world, a sannyasi submerged in nature. After Aparna's death the film becomes female-less, whereas the book constantly brings Apu in contact with female characters. Ray's narrative of modernity is far more brutal than Banerjee's because, in the cinematic representation of Pather Panchali and Aporajito, all the female characters must die before Apu can purify himself in nature again to emerge as a matured modern subject. The last scene of Apur Sansar shows Apu carrying Kajol on his shoulder, there are no females, nor are their memories in the vicinity. Thus, Ray's depiction of the patriarchal tale of modernity is normalized as a universal story of humanity. Rubaiyat Hossain is an independent film-maker and Lecturer at Brac University. |

One curious feature of this journey towards modernity is the constantly surviving male figure (Apu) versus the failed and dead figures of the females (Indir Thakuran, Durga, Sarbajaya, and, finally, Aparna).

One curious feature of this journey towards modernity is the constantly surviving male figure (Apu) versus the failed and dead figures of the females (Indir Thakuran, Durga, Sarbajaya, and, finally, Aparna).