Inside

|

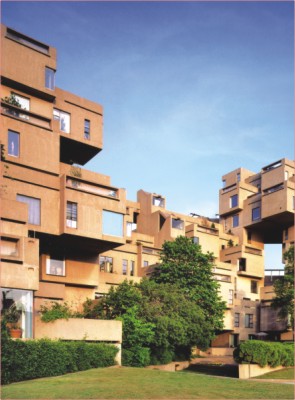

Moshe Safdie comes to Chittagong Ismat Hossain marvels at the boldness of the design proposed for AUW's Chittagong campus by the world-renowned architect For those who remember the stunning exposition of Habitat '67 at Montreal, Moshe Safdie is a name they are not apt to forget. The amazing cellular amalgamation of pre-fabricated "modules" was a later adaptation of his thesis, and became the central feature of the 1967 World Exposition held in Montreal.

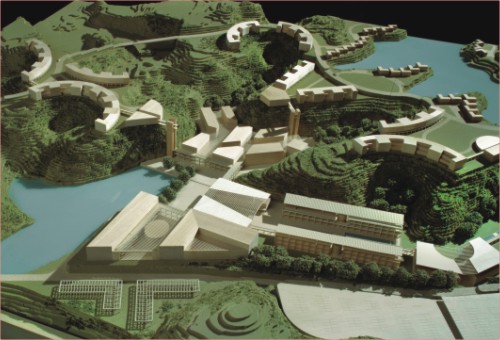

The Asian University for Women (AUW) is an international effort to establish a world class university for women from all religious, ethnic, and socio-economic backgrounds from across South, Southeast, and Southwest Asia and the Middle East -- with particular emphasis on serving women from economically underprivileged, rural, and refugee communities. It is being established under a special act of the Parliament of Bangladesh, approved in September 2006, that creates a truly independent institution with guarantees of academic freedom. The focus of the initiative is to create capable, dynamic, and innovative women who will ultimately become leaders in the professional and civic realms. These women, they hope, will help encourage and direct sustainable human and economic development in this region of the world. In partial fulfillment of their aspirations, the founders of the university called on Moshe Safdie and Associates Inc. to create a place that would at once be inspirational and liberating, and yet comforting and close-knit. They envisioned a place that would be international in scope but, at the same time, embedded in the contexts of the region. At first the unique topography of the site presented a major challenge to the master planners. The site, a total of more than 100 acres, comprises a series of steep, rolling hills and narrow valleys. The soil formation on both the hilltops and the valleys was not at all suitable for bearing heavy structures. A study into the local climate quickly made them realize that the valleys held the danger of being flooded during the torrential rains of the monsoon. The hilltops themselves were narrow and steep, making them incompatible for construction. Presented with little "available" land on which to build, Moshe Safdie came up with a solution that eventually developed into the unique concept of a "multi-layered" campus, i.e. a vertical juxtaposition of separately operable horizontal layers containing different programmatic elements that are connected by, sustain, and reinforce each other through a series of elevators and stair towers.

Safdie's master plan for the AUW campus has come far from his "metabolist" beginnings. Yet, the underlying principles of creating architecture that can operate as a living organism, and correspond to and take shape from its environment, still exists. Influenced by drawings and ideas from Archigram, the "Metabolist" movement started in Japan around 1959. The architects and planners associated with the movement envisioned architecture and the city as a large scale, flexible and extendable structure that enabled an organic growth process. Corresponding to living organisms, the symbiotic units of "upper campus" blocks and "lower campus" blocks in the AUW master plan, along with their connecting towers, create a "phenotype" -- a sustainable system for architecture that can be continuously repeated throughout the campus as it expands. Another organising element developed by Safdie is the network of covered exterior arcades. These arcades become the connective tissue that links all of the buildings on the campus. However, like all biological systems, this unit also allows for flexibility, adaptability and mutations that may occur due to changes in programmatic requirements or other external factors. The master plan, or "genotype," thus lays out a system for locating buildings, infrastructure, circulation, drainage and water and vegetation, guidelines for massing and orientation, as well as land coverage ratios. Phased out through a span of seven to ten years this framework of programmatic typologies allows a desired amount of flexibility and robustness that may embody future shifts and changes. Apart from the topological challenges, the unique climate and cultural context of the site also imposed demands on the imagination of the architects. Excessive rainfall and humidity were two other prime issues that were given due consideration. A system of continuously linked arcades that horizontally connect all the building blocks, and circulation shafts at all layers throughout the campus, ensures that pedestrian movement goes unhindered even in the most horrid weather. Even at full build out the master plan uses slightly less than 20% of the land -- leaving 80% available for re-vegetation and environmental protection. The architect and his team were especially sensitive to the need for creating an environmentally sustainable campus throughout the entire design process. The delicate balancing of soil cutting and filling, the use of solar profiling (i.e. positioning the broad side of buildings away from direct sunlight to reduce energy consumption by half), water control to protect the site from soil erosion damage, and water retention which can then be used to produce hydroelectric power and can also be used as grey water for the campus, are some of the numerous ways in which the architect has provided scope for creating an energy-efficient and sustainable campus. The use of air conditioning was required because of the international student body. However, each classroom/ lecture hall is provided with individually controlled temperature gauges so that classrooms that are not in use can turn off the heat/air conditioning to save energy. Environmental elements such as water and the landscape provide a crucial role in the formal development of the master plan as well. The way the residential facilities follow the natural contour lines atop the ridges reinforces the natural topography and also creates an edge to the campus. The use of locally produced building materials and locally available building technologies also reflect the architect's concern for a contextual architectural solution, not to mention his zeal for curtailing construction costs. One of the major aspects of campus design is the provision of spaces that spawn interaction -- spaces where students and faculty can meet, interact, debate issues and learn social interaction skills in general. The importance of constructing spaces for public use, along with creating a place for the individual, was conceived by the AUW initiative and has been handled with utmost care by the master planners. Ample indoor and outdoor informal meeting places have been placed throughout the campus in the form of open and semi-open courtyards, gardens, arcades and an amphitheater. The overall zoning of the master plan also addresses the issue of organising spaces, from public through semi-public, semi-private and private zones. The academic zone is segregated into an hierarchy of public and privately shared and accessible spaces -- starting with the Entrepreneurship Centre used for public and private events, Performing Arts Centre for musical and theatrical performances, Health Centre to serve the campus and provide some health care to the local community, the School to serve faculty children and students from Chittagong, and then gradually moving on to the more reclusive academic buildings of the campus. The upper layer of the campus holding the residential blocks not only overlooks the vivid scenery of the water bodies beneath but also provides the necessary privacy and segregation for the living units from the crowds and clutter of the academic zone. This creates potential for the students and faculty to define their own domain, inculcate a sense of belonging and, at the same, time provide opportunity for interaction and integration.

The master plan of the AUW campus is definitely an unconventional approach to designing a university in an even more unique landscape. Actualisation of the project will undoubtedly be an even bigger challenge for the consultants as they progress from master planning to architectural design and have to battle the terrain to materialize their ideas into concrete forms. The site being as it is, curbing the flow of rain water and preventing soil erosion will present great challenges to the actual construction process. Another challenge that remains is the tectonic detailing and coherent designing of the buildings, which will eventually be carried out by Safdie as well as local consultants from Bangladesh. However, the spatial framework that Safdie has laid out in the midst of a scenic landscape will hopefully pave the way for yet another internationally recognised architectural site in Bangladesh that we can boast of. Ismat Hossain an architect and part-time Faculty, NSU, was a key-member of HAQ-SNAL Consortium which won joint first prize for the Design competition for North South University in 2002.

|

While seemingly random, the huge apartment complex is actually an optimised programmatic arrangement in which all residential units receive the maximum benefits of private gardens, natural air, sunlight, and views. Fresh from his apprenticeship in Louis I. Kahn's office in Philadelphia, Safdie's systematic, bold and visionary approach towards architecture immediately put him in the spotlight of the international architecture scene. Since then, he has strengthened and consolidated this position through several significant architectural and urban design projects throughout the world. Forty years later, his expertise and ingenuity come to play in the luscious, rolling landscape of Chittagong.

While seemingly random, the huge apartment complex is actually an optimised programmatic arrangement in which all residential units receive the maximum benefits of private gardens, natural air, sunlight, and views. Fresh from his apprenticeship in Louis I. Kahn's office in Philadelphia, Safdie's systematic, bold and visionary approach towards architecture immediately put him in the spotlight of the international architecture scene. Since then, he has strengthened and consolidated this position through several significant architectural and urban design projects throughout the world. Forty years later, his expertise and ingenuity come to play in the luscious, rolling landscape of Chittagong. This became possible by reprofiling the loose top soil from the hill tops to create small plateaus on which the residential facilities of the university, or the "evening campus," could be placed. This soil was then relocated into the valleys to create elevated platforms that could escape the effects of flooding. These platforms accommodate the academic zone, or the "daytime campus," and would be surrounded by water reservoirs and a complex drainage system that could drain out excessive rainfall in the monsoon. An innovative and rationally organised solution for creating an environment that allows for a complex range of activities, from public and academic to private and leisurely, to be accommodated in one place yet not hampering each other.

This became possible by reprofiling the loose top soil from the hill tops to create small plateaus on which the residential facilities of the university, or the "evening campus," could be placed. This soil was then relocated into the valleys to create elevated platforms that could escape the effects of flooding. These platforms accommodate the academic zone, or the "daytime campus," and would be surrounded by water reservoirs and a complex drainage system that could drain out excessive rainfall in the monsoon. An innovative and rationally organised solution for creating an environment that allows for a complex range of activities, from public and academic to private and leisurely, to be accommodated in one place yet not hampering each other.