Inside

|

Fakrul Alam runs a critical eye over an NRB professor's intriguing and interesting look at Bangladeshi politics

|

Bangladesh in the Mirror: An Outsider Perspective on a Struggling Democracy. A. T. Rafiqur Rahman. Dhaka: The University Press Limited, 2006 (Tk 550.00); 383 pp. |

Bangladesh, it must be remembered, had switched to a form of democracy in 1996 where the ruling party would hand over power to a "caretaker government" for a period not exceeding three months so that free and fair elections could be ensured. The system had worked well that year and had eventually brought the Awami League into power at the expense of the BNP. In 2001, too, there was a reasonably smooth transition because of the caretaker system. This time it was the Awami League which had to hand over power to the BNP.

Unfortunately for the proponents of the caretaker form of government, the leaders of BNP then decided that there was no point in relying on a neutral administration during electioneering any more if they wanted to remain in power since the order of politics in Bangladesh seems to be that the party in power always loses. Consequently, the BNP leaders engineered a number of moves throughout its term to ensure that the administration, the judiciary, the forces responsible for maintaining law and order during elections, and the election commission itself would tilt their way by the time the next election came around.

|

Amirul Rajiv |

The icing on the election cake they had concocted for themselves, they must have thought, was the fact that the president had the right to choose the head of the caretaker government. After all, President Iajuddin Ahmed was their man, and wouldn't the "chief adviser" and the "advisers" he chose to run the caretaker government virtually guarantee BNP's success in the elections? The Awami League and its coalition partners, however, had been schooled too long in what A. T. Rafiqur Rahman calls in his book Bangladesh in the Mirror: An Outsider Perspective on a Struggling Democracy, "andolon politics," that is to say, the "politics of confrontation" to let the BNP government have its way. Such politics had emerged out of years and years of experience which had taught them that "the politics of tolerance and compromise" rarely worked and that aggressive tactics often did.

They had come to believe that more often than not democratic institutions were co-opted by authoritarian leaders who mouthed the mantras of democracy only to perpetuate their hold over the country. And so the first eight or nine months of 2006 passed with the opposition threatening to shut down the entire country and the BNP making a show of negotiations but never making any real concessions to the concept of free and fair elections. President Ahmed, for his part, proved conclusively in his choice of election commissioners and in his eventual unconstitutional appointment of himself as the chief adviser that his only agenda was loyalty to the party that had elected him to the highest position of the country and not the constitution he was supposed to safeguard.

|

Amirul Rajiv |

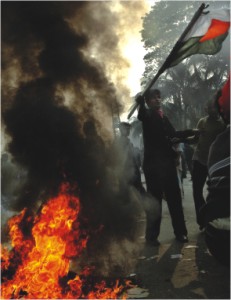

The last few months have thus proved to be bloody, disruptive, and depressing for anyone who loves Bangladesh and who does not want it to be seen as a country which the world notices only when either natural or man-made disasters devastate it. Here, indeed, was every recipe for catastrophe: a dysfunctional state, a partisan administration, an economy debilitated by frequent hartals, corruption on a scale that has made the country a perennial frontrunner in the Transparency International ranking of the world's most corrupt states and to top it all, violent bomb blasts and bloody street battles being recorded with sickening regularity. All the mayhem, however, has stopped for the time being, and Bangladesh's experiment with democracy, which had begun in 1991 when the first caretaker government took over after the army dictator General Ershad was overthrown by the people, was over by January 11. On that day an army-backed crackdown fronted by a completely new and apparently quite neutral caretaker government had marginalized President Iajuddin Ahmed and had reduced him once again to the figurehead the BNP had wanted him to be when it was in power.

Was Bangladesh's slide into chaos inevitable and did the democratic phase of its history have to end so depressingly? One of the many virtues of Mr. Rahman's "outsider perspective" on the country, Bangladesh in the Mirror is that it clearly indicates that the democratic experiment had reached a dead-end by the beginning of 2006 and that something drastic had to be done sooner rather than later if the country's institutions continued to crumble because of the machinations of the greedy, power-hungry and brutal politicians in power and the aggression, intolerance, and obduracy of the politicians in the opposition camp.

Mr. Rahman is not really an outsider though; he may be living the life of an expatriate in the US since 1971 but he writes as a Bangladeshi intellectual and "expert" distressed by developments in his home country and concerned about its future. He also looks at Bangladesh from his scholarly vantage point and his rich experience of Bangladeshi political institutions: he is currently Professor in Public Administration at the City University of New York but has also taught at the University of Dhaka and has led three UN studies on Bangladesh's public administration sector, local governance mechanisms and human security situation. From this vantage point he articulates these home thoughts from abroad and offers some home truths for Bangladeshis to consider.

What Mr. Rahman wants to do, in effect, is make his Bangladeshi readers "look critically in the mirror" to see what they had become and compare that image with their "aspirations at the formative period." The sustained gaze reflects five notable features: political instability and constant pursuit of the politics of confrontation by the leading political parties; a "culture of conflict and confrontation, rather than the development of strong institutions;" preoccupation with "self and group interests and indifference" to national and public welfare; persistent and perverse use of student politicians in the often vicious politics of the country since parliamentary democracy was restored in 1990; and a Parliament where nothing happens because the government skirts it and the opposition refuses to engage in the little that is allowed to happen in it and therefore the lack of a democratic culture at all levels of government.

Mr. Rahman identifies some worrying tendencies in politics since 1991 that he feels is "influencing civic behavior and distorting democratic values" and is taking the country closer and closer to chaos. The first symptom of malaise that he notices stems from the way Bangladeshi politicians focus exclusively on "short term and immediate considerations" and their indifference to "long-term perspectives for building sustainable political, administrative and development processes."

The next problem that worries him is partisanship in general and the "winner-take-all" strategy pursued with vengeance by the political party that has just won an election. Almost inevitably, this means that politics has become a fierce race where the participants are motivated by the idea that the intensity of their commitment will have to be rewarded by their party with monetary rewards and powerful positions.

One result of these trends is a scramble for power and wealth, a decline in the quality of public service, and often, the diversion of public money for personal profit. Another is the nexus between organized crime and self-seeking politicians. The criminalization of politics, in turn, means that educated and professional groups have been disempowered at the expense of corrupt and power-hungry people. In the process even parliamentary elections have been seen as investments since once elected a member has the opportunity to get a substantial return on his investment.

The bulk of Mr. Rahman's book consists of a series of case studies of the many different manifestations of the rot that has been vitiating Bangladesh's political fabric and endangering its democratic institutions. Relying mainly on press reports published over the years, he provides documentary evidence of how in their pursuit of power both the Awami League and the BNP have adopted policies that have contaminated professional groups such as teachers, physicians, lawyers and the civil service as well as tainted student politics. He notes that both parties resort to incessant hartals when they are in opposition but are unabashedly vociferous in denouncing them when in power. He is able to show that the result has been virtual indifference to the rule of law and repeated breakdown in law and order. Inevitably, this situation has contributed to the rise of terrorism on the one hand and widespread violations of human rights on the other.

Indeed, Mr. Rahman implies that bad governance has brought Bangladesh perilously close to being a "failed state;" he suggest that its democratic institutions have withered in a climate of intolerance, opportunism, and partisanship. He narrates the sad story of every Parliament since the restoration of democracy in 1991: biased and domineering tactics applied by the government in the first few months and confrontational tactics used by the opposition then; subsequently, non-attendance in parliamentary sessions and parliamentary committees by members of both the government and the opposition; afterwards, virtual monopoly rule by the government and frequent walkouts and constant non-cooperation by the opposition; ultimately, brutal measures adopted by the government to thwart extended periods of general strikes organized by the opposition with increasing frequency as the government came close to finishing its term. The net result is that successive governments have only been able to limp to the end when in office while the nation as a whole has suffered "serious dislocation and damage to both public and private businesses and operations as well as social, cultural, and educational life."

Is it any wonder, then, Mr. Rahman implies, that fundamentalist parties have been able to increase in power in a situation where the opposition as well as the government have dithered about the job they were elected to do and have been distracted by greed and malice from the roles they were elected to play in a parliamentary democracy? Taking advantage of a situation where secular nationalism is being constantly discredited, all sorts of religious organizations and Islamic NGOs, many of whom seem to be funded by Islamic fundamentalists based in the Middle East and the West, have been mobilizing to attack secular institutions such as the judiciary and to carry out attacks on mainstream political parties. One alarming manifestation of this is the wave of bomb blasts carried out by one particularly violent fundamentalist party, the Jamaatul Mujahidden Bangladesh (JMB) throughout 2005 till its leaders were caught. As Mr. Rahman observes: "JMB's action should be a wake up call for democratic forces -- ruling and opposition parties alike," alerting them to "practice democracy and solve problems and not just enrich themselves and their supporters perennially through corruption, expropriation and abuses of government power."

Mr. Rahman, however, is no pessimist and one of the welcome features of his book is his belief that Bangladeshis can reform their institutions and initiate another phase of politics in the country that will lead them back to healthy democratic practices and efficient governance.

He notes that the country has been doing well economically and has been maintaining "a 5 to 6 % level of GDB growth over [the] last few years," and that "its achievement in education and health, especially evidenced by quantitative features, has been impressive." Most chapters of his book come with a set of recommendations for improving the economy, educating the public in democratic values and practices, restructuring government and educational institutions to make them transparent, accountable and efficient, and free from political interference. He is all for reorganizing the judiciary and the police, and taking the country back to the road of secular nationalism paved when Bangladesh got its first constitution in 1972. Befitting a student of public administration, he is at his best when suggesting reforms to local government bodies and giving them autonomy, for he believes firmly that they hold the key to democracy, stability and development and not governance imposed from the capital , Dhaka, by self-seeking and indifferent politicians and bureaucrats.Bangladesh in the Mirror is thus a useful book and should be required reading for people who would like to see Bangladesh emerge from the quagmire of violence, lawlessness and corruption it had sunk into and from which it has been apparently rescued, at least for the time being, by its armed forces and the present caretaker government. Would that the book was written better and that the publishers had spent more time giving us a carefully edited and proofread work! It is sad indeed to see a book written out of the immense love and obvious concern the expatriate Bangladeshi has for his country of birth presented in such an execrable state. It is unfortunate, too, that someone like Mr. Rahman who has taken so much care to marshal his evidence should have been so careless and rushed in writing it. It is really surprising to find someone of Mr. Rahman's stature and years of experience teaching in America and working in international organizations making some very elementary grammatical errors and producing clumsy sentence after sentence that can only make any lover of the English language wince again and again. In addition, it must be said that the book could have been structured much better, for halfway through the book one finds Mr. Rahman making the same point repeatedly. Finally, it must be pointed out that while Mr. Rahman is very good at talking about issues related to governance and administration he skirts subjects such as leadership and has relatively little to say about ideology and the political economy of Bangladesh, for surely murky ideologies, the rising inequalities in the country, the terms and conditions of employment of officials at all levels of government, and the financial system should also have been dealt with adequately in coming to terms with the malaise afflicting it.

Still, despite the considerable limitations noted above, there is a lot to be gained from reading Rafiqur Rahman's Bangladesh in the Mirror: An Outsider Perspective on a Struggling Democracy. One can only hope that policy-makers and friends of the country will read the book carefully and will consider its diagnosis of the country's problems and its recommendations with the same seriousness and intense engagement that went into the writing of it. And, hopefully, Mr. Rahman will eventually find an occasion and an editor to help him redo the book and come up with another edition that reads much better and is less riddled with typos and mechanical errors than this one. We need more studies such as this book so that Bangladesh's politics can be overhauled completely and the country can leave the trauma of the last year far, far behind.

Fakrul Alam is Professor of English at the University of Dhaka. His most recent work is South Asian Writers in English, a volume in the Dictionary of Literary Biography series.