Inside

|

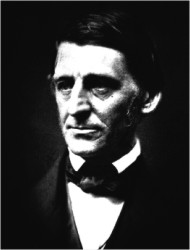

Emerson and Islam Syed Ashraf Ali shines a light on how Islam affected the thinking of the great American transcendentalist

Emerson believed that each man must think for himself and act on his own best instincts. In his words: "What is a man born for but to be Reformer, a Re-maker of what man has made; a renouncer of lies; a restorer of truth and good, imitating that great Nature which embosoms us all, and which sleeps no moment on an old past, but every hour repairs himself, yielding us every morning a new day, and with every pulsation a new life? Let him renounce everything which is not true to him, and put all his practices back on their first thoughts, and do nothing for which he has not the whole world for his reason." It was not only through his intimate acquaintance with Thomas Carlyle, who became a lifelong friend, but also translations and scholarly works available to him in New England and Great Britain (which he visited in 1833) that Emerson was imbued with a clear perception of Islam and its tenets. "After a long period of misunderstanding of Islam," according to renowned researcher Farida Hallal in Emerson's Knowledge and Use of Islamic Literature (University of Houston, 1971), "Fresh efforts were made in Emerson's time to approach and present Islamic culture objectively. Emerson's own attitude towards Arabic and Persian literature and culture reflects this more liberal interpretation." Emerson's assertions about Islam reflect the fact that he was more interested in specific manifestations of the spirit of the religion -- as exemplified in sayings and events -- than in its dogma as a whole. Emerson's interest in the Near East being part of his eclecticism and transcendentalism, he tended to use Islamic and Arabic concepts as emanations from a certain area of the Over-Soul rather than as manifestations of specific dogmas. Yet, out of the mass of his reading, he selected only those ideas and actions that corresponded to his most immediate preoccupations and concepts of expression. Although Eastern culture was known incompletely in New England, Emerson had read an unusual number of books on the subject. The Islamic concepts that he retained were the notion of a meaningful world, the concept of the virtue of temperance, and the ideal of self-reliance. In the Arabian history he found an illustration of his ideal of a religion of the heart that did not deny reason its place as opposed to a stern, exclusively intellectual religion. He was attracted to social values that had evolved with the rise of Islam, and to other specific characteristics of Arabian culture, such as hospitality and regard for women. An out and out transcendentalist as he was, Emerson found in the Holy Quran an equivalent of the transcendentalist belief that the world has order and purpose. He quoted twice from the Holy Quran in his "Representative Men" to emphasise that the economist, the philosopher, and the poet are less apt to meet man's metaphysical needs than the moral thinker or spiritual leader who tackles the basic problems of existence: "The instincts presently teach us that the problem of essence must take precedence of all others-the question of whence? and whither? ... The atmosphere of moral sentiment is a region of grandeur which reduces all material magnificence to toys, yet opens to every wretch that as reason the doors of the universe. In the language of the Koran, 'God said: the Heaven and the Earth and all that is between them, think ye that We created them in jest and that ye shall not return to Us?'" In his writings, Emerson also displayed familiarity with the stress in Islamic religion upon culture as a means of fulfilling the individual's humanity and improving himself both intellectually and spiritually. He was well aware of the fact that knowledge is considered in Islam as both an incentive to humility and a preventive against blind, superficial faith. In "Worship" Emerson expressed himself in favour of an intellectualised religion and used a saying of the holy Prophet Muhammad (SM) to bring home his point: "The religion which is to guide and fulfill the present and coming age, whatever else it may be, must be intellectual ... 'There are two things,' said Mohammed, 'which I abhor: the learned in his infidelities, and the fool in his devotions.' Our times are impatient of both, and especially of the last." Late in his life Emerson again turned to the holy Prophet of Islam. At the opening of the Concord Free Library, he said: "We expect a great man to be a great reader or in proportion to the spontaneous power that there should be assimilating poser. There is a wonderful agreement among eminent men of all varieties and conditions in their estimate of books .... Even the wild Arab Mahomet said: 'Men are either learned or learning. The rest are blockheads.'" In his early notebooks, he recorded a sentence of Hazrat Ali (RA) on the subject: "Knowledge calleth out to practice: and if it answereth, well; if not, it goeth away". He used the same quotation to illustrate a similar point in "The Method of Nature." Emerson's pragmatic mind found in Arabic literature and history examples of the virtue of temperance which he himself had exalted in several ways. Besides moderation in faith, he was also impressed by the Islamic concept of moderation in manners which had been an important virtue of the early Muslim leaders. Caliph Omar in Khattab's behaviour in wartime, as described by Ockley, offered him a living image of this virtue. In 1840, he noted in his journals: "Omar's walking stick struck more terror into those that were present than another man's sword. His diet was barely bread, his sauce salt; and oftentimes, by way of abstinence he ate his bread without salt. His drink was water. His palace was built of mud. And when he left Medina to go to the conquest of Jerusalem, he rode on a red camel with a common platter hanging at his saddle with a bottle of water and two sacks, one containing barley and the other dried fruit." In "Man the Reformer," Emerson used this passage again to describe Omar and what he termed as his "temperance troops" as an example of the detachment of those who are motivated by high enthusiasm and faith. Islamic history also provided him with an example to illustrate another essential heroic quality -- self-reliance. He was particularly attracted to the character of Hazrat Ali bin Abu Talib, whose proverbial self-reliance was so strong that he refused to "campaign" for the succession of the caliphate: "In his consciousness of deserving success, the caliph Ali neglected the ordinary means of attaining it." Ali's heroism was enhanced by another quality Emerson cherished -- a sense of humour. He cited a quotation describing the caliph as an example of both humour and self-reliance: "The caliph Ali is a fine example of character. He possessed a vein of poignant humour which led Solyman Farsy to say of a jest he one day indulged in: 'This (joking) is what has kept you back to the fourth' (Abu Bakar, Omar, and Othman, having been successively elected to the caliphate before him)." Emerson's concept of fate was also to some extent influenced by Islam. In his interpretation of the Muslim view of the subject, he displayed an amazing ability to grasp the positive facets of this belief. In 1840, he wrote: "I read today in Ockley a noble sentence of Ali, son-in-law of Mohammed. 'They lot, or portion of life, is seeking after thee; therefore, be at rest from seeking after it.'" Emerson also found in Islam a concept of seriousness akin to his own. Although he valued humour, he felt that the touchstone of a sincere conviction was an earnest attitude that admitted of no trifling with principles. In "Social Aims," he resorted to the Holy Quran as a repository of the wisdom of the ages to give sanction to his point of view: "And beware of jokes, too much temperance cannot be used: inestimable for sauce, but corrupting for food, we go away hollow and shamed ... True with never made us laugh ... In the Koran (is mentioned): 'On the Day of Resurrection, those who have indulged in ridicule will be called to the door of paradise, and have it shut in their faces when they reach it. '" [Emerson mistakenly quotes the Quranic sentence. The actual version is: "And leave alone those who take their religion to be mere play and amusement, and are deceived by the life of this world." (6:70)]. In short, Ralph Waldo Emerson, in spite of a certain degree of misunderstanding of Islam, was more attuned to some of the fundamental principles of the religion than he was aware. It is true that he was not, like Washington Irving, the "first discoverer of Islam in the United States of America." Nor did he champion the excellence and beauty of the holy Prophet Muhammad (SM) as his friend Thomas Carlyle had done. But even then his projection of the virtues and serenity of Islam, its holy prophet and caliphs helped remove the misunderstanding looming large for centuries over the hearts of Americans and Europeans hitherto shrouded by ignorance and hatred of the essence and excellence of Islam. Syed Ashraf Ali is former Director General, Islamic Foundation, Bangladesh. |

R

R