Inside

|

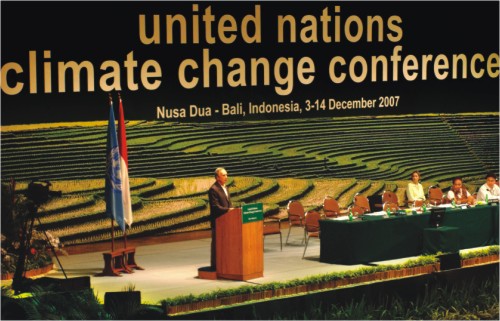

Is the US stronger than global opinion ? Afsan Chowdhury asks the all-important question in the wake of Bali Now that Bali is done, everyone is glad it's over and can decide whether it's a success or a failure. Most have been cautiously optimistic because there is a sense of relief that the US has not completely abandoned the consensual ferry that is supposed to carry the world to safety and, instead, taken to its own private yacht to unilateralism.

While ostensibly a meet to discuss ways to curb global climate change, the Bali conference has been a stark reminder of how asymmetric and misbalanced global relationship has become. Obviously, the US doesn't think the rest of the world and it share the same planet. The Bali meeting was meant to devise a "roadmap" that would take the global community forward beyond the Kyoto Protocol which set the carbon emission targets for the world in 1997. It is derived from the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCC). The remit of the Kyoto Protocol --flouted by all signatories, incidentally -- ends in 2012, so new targets, goals, and processes need to be agreed upon. The Bali meeting was expected for that goal, which is likely to be sewn up at the final meeting to be held at Denmark in 2009. The US didn't ratify the Kyoto Protocol -- and nearly sank the Bali meeting, too. It's also necessary to understand why the US can afford to ignore global opinion on this issue. The answer is simple, and also frightening. It is far too powerful and rich at this point of time to care about what the rest of the world thinks. There is a firm belief now in the rich world that, given its wealth, the US can escape the harshest impacts of climate change through technological fixes and expensive impact management. Although climate change impacts have been billed as dangerous by the UN and endorsed at the Bali meet, including by the US, it doesn't seem that the US shares a global vision. This was a point made by US leaders, as well, including Nobel winner Al Gore, who stated the "inconvenient truth" that the US was largely responsible for the problem. At Bali, the US systematically attacked every argument, alliance, and construction, knowing that it was in a unique position of strength compared to the rest of the world. The US delegation went to the conference on the prime mission to battle mandatory emission cuts. It was proposed that all the advanced countries should cut carbon emission by 20% of 1990 levels by 2020. The European Union argued for a 25 %-40% cut as the minimum required cut by that date. The US was against this position, and, instead, said that cuts should not be binding but voluntary, and China and India had to agree to cuts as well, as both countries were large emitters. In this argument, they were supported by Canada and Japan. In the end, the US argument held sway and the EU proposal was withdrawn. The battle between the developed and the developing However, both China and India need to be energy efficient, and to improve their pollution practices. The search for alternative renewable sources is also urgent. Both countries state that they are going forward in this regard. China has laid down its energy use plan, whereby it plans to shift 10% of its energy resources to wind, solar, and other renewable sources. China is considered particularly polluting because it gets two-thirds of resources from high polluting coke and coal plants, and, between 1974 and 1984, increased carbon emissions by 4% every year. However, China has said that its main priority is poverty alleviation of its millions, and that it will not be bound by any mandatory targets. India has yet to spell out its plan in great detail, but its claim to spend energy to reduce poverty of its millions is accepted given its economic status at this point of time. It uses coal to a lesser extent than China, and its interest is in nuclear energy required to reach or sustain its high growth rate. Before the Bali summit, it released a series of papers where it stated that the UNFCC is clear about India's right to emit to reduce poverty, and no mandatory targets would apply to it. It further stated that India was already investing in renewable sources including wind and solar energy. In fact, India is one of the leading producers of alternative fuels, but compared to its need this is far from being enough. The demand that India and China fall in line with the developed world was a call from the US and Canada, and was seen as a bargaining chip at the meet by the US group to force the hand of others and allow it to fend off the demand for mandatory targets global opinion was seeking. Canada brought the issue up at the Commonwealth meeting in Uganda this year, and its PM, Stephen Harper, was roundly criticised at home and abroad for it. However, the present Canadian government preferred to follow the US footsteps, though Canada at one time was considered a leading voice within the western world for an eco-friendly and globally equitable policy to combat climate change.

Mood metre at Bali The EU and the US were also confrontational at the meet, but as days progressed and the world negotiated, bickered, and argued, it was obvious that the US alliance was not ready to compromise. At this point, two US politicians of significance dropped in, both ex-US presidential candidates. One was Nobel Prize winner Al Gore and the other was Sen. Kerry. Both came and criticised the Bush administration roundly. Gore said that his country, the US, was the major cause of climate change creating emissions, and Kerry added a hopeful note saying that there would be a new government in Washington soon -- Democrats -- and it's going to be far more sympathetic to climate change issues. While this was loudly cheered and made the present US administration look like the villain of the piece, it didn't budge them from their highly professional approach to scupper the conference goal of finding a roadmap to work towards building a successor to the Kyoto Protocol. The situation became bad enough for the UN SG Ban Ki-Moon to fly in to accelerate the process. Meanwhile, the G-77 and the EU, both greatly moderated their positions. The 130 member G-77 spokesperson has since then said that even a year back they would not have agreed to such a language formulation of the final draft, but did so because so much was at stake. The EU, meanwhile, backed down because it was clear that as long as the clause of binding targets was on the plate, the US would never agree. In the end, quite dramatically, the US did agree, saying that they were always in favour of a positive solution. The US, however, agreed only after the points it wanted removed were done so. The US set the terms under which the Bali talks progressed. This was the most quietly swaggering show of power that the US has displayed in recent times. It has implications for the rest of humankind and its history. Bali gains, losses and the US The supremacy of the US was never in doubt at the conference, and it was dubbed as "the wrecking ball" as it demolished every proposal and refused to give away any ground. In fact, the decision at the final hours is something of an anti-climax and one doesn't really know for sure what motivated the US to finally agree. Domestic politics and international problems The meet also came at a time when the US Congress is debating passing an energy bill, which is the most far reaching as far as having a more rational energy policy is concerned. It has overwhelming Democrat support. So the political pressure on the Republicans was probably heavier than before. This may have influenced the Bush government to go along after gaining their major victory, which was the withdrawal of the EU sponsored mandatory cuts proposal. Some argue that this was a smart move as the Republicans look better than they did before, especially for a party that had denied that climate change was happening, and it takes the wind out of the Democrats' sail. Since the nitty gritty of what is to be done comes later, agreeing now gives them breathing space and political comfort. But whichever way one looks, the issue of global survival is still dependent on the whims of the US's domestic political breeze.

The relief of the leading members of the various delegations after the US affirmation was tremendous. Everyone agreed that without the US no step forward could be taken. Many activists were, however, unhappy with the outcome, saying that a great opportunity had been lost. This is true, but such disappointment is unrealistic because it doesn't take into account the fact that global climate change is largely centred on decisions taken largely by a single country. Perhaps global public opinion is a myth of sorts. In the end, one is left waiting for more, and in suspense. Just because the Bali roadmap has been signed doesn't mean anything, as the US can break away any time it wishes. Its leaders care about what the US voters think, and till they decided to tilt in favour of an international arrangement to counter climate change and act to prevent the end of a future as we know it, we shall have to wait and see and hope that the US does the right thing. Afsan Chowdhury is a journalist writing for Bangladeshi and South Asian publications. Photos: AFP |