Inside

|

The Trial we are Still Waiting for Julfikar Ali Manik asks how much longer we will have to wait for justice Let's look just a year back, to December 2008. The whole nation was at a virtual stand still. We were awaiting the ninth parliament election results with a feeling of great enthusiasm and eagerness. Yet that enthusiasm was set against the backdrop of political turmoil that the public could endure no longer. The excitement was for the return to democracy in the month of December, the month of glory for Bangalees, the month in which we were victorious in our war of independence and the month in which the non-elected caretaker government finally stood down. In the years that have passed since independence the demand to try war criminals from 1971 has not faded, but instead became a major issue before the ninth parliament election as it was demanded afresh from all corners of society (except of course by alleged war criminals, their forums and supporters). A commitment to try war criminals was expected from the major political parties prior to the election. Hasina's election pledge about trying war crimes uplifted the spirits of not only the party workers, but gave hope to the entire nation despite its growing disillusionment from past experience of successive governments including the AL's, of ignoring this popular demand. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's government had initiated the trial of the war criminals but could not continue due to the horrific events of 1975. The onus had been on all the governments that followed, some of which assumed power illegitimately or legitimately. Sadly, even the elected governments did not make the trial of war criminals a priority. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is pledge-bound to try the war criminals especially as her election pledge about war crime has been endorsed at the ballot. There is little doubt that it was her promise to try war criminals that helped her to bag people's landslide mandate. After the Grand Alliance's landslide victory she said, "People have already 'tried' the war criminals and the anti-Liberation forces through ballots, but our government would obviously take legal steps to try them." This, together with Hasina seeking support from the UN to bring war criminals under trial, has given people the hope that she is committed to her promise and intends to carry it out. Their confidence and dreams to see justice are evident in the January, 9, 2009 issue of The Star magazine. There the cover story dealt with the trial of war criminals of 1971 soon after the election results in December where the cry for justice had been bellowed repeatedly. Ferdousi Priyabhashini, one of the survivors of the 1971 war crimes, said, "I am really optimistic this time about the trial of war criminals. I am also eagerly waiting to deposit my witness as a victim in the war crime tribunal, which should be set up as quickly as possible." Ferdousi, who is also a renowned sculptor of the country, already gave her testimony in many publications. She was imprisoned and tortured by the Pakistani occupation forces and their collaborators in Khulna during the nine-month bloody liberation war in 1971. She witnessed the genocide, atrocities and destruction of the occupation force. "As a witness I know many names of war criminals from the Pakistani army and their collaborators, I can place my deposition before the court when the tribunal is set up for the trial of war criminals," she says. Dr MA Hasan, convener of War Crimes Facts Finding Committee (WCFFC) says that there is enough evidence to try the war criminals of 1971. "We have many victims still alive, witnesses to the atrocities, documents and other evidence," he says. Deputy Chief of Liberation Forces Air Vice Marshal (retd) AK Khandker, former advisor of caretaker government and human rights activist advocate Sultana Kamal, war crime researcher and human rights activist Shahriar Kabir and many other experts equally expressed their confidence about the availability of the evidence even after a lapse of 37 years. "If it was possible to try German Nazis fifty years after their war crime," says Khandker, "there is no question of not holding trials of war criminals of 1971 after 37 years." According to Ghulam Rabbani, former judge of Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, the necessary documentary materials for convicting the collaborators including the killers of intellectuals are all with the home ministry. "Since the materials are more than 30 years old, according to the Evidence Act those are to be treated as ancient documents," explains Rabbani. "No other evidence is required as those at the disposal of the ministry would be sufficient as exhibits in the case records, and conviction and sentence on the basis of that are very much possible."

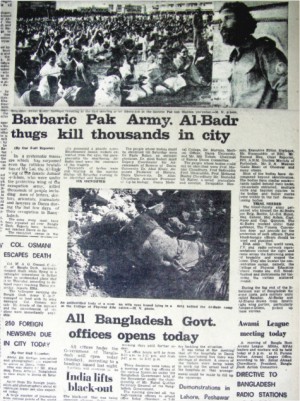

Some people engaged with the long movement for trial of the war criminals think the UN and international community can help Bangladesh, providing valuable documents and evidences of 1971 exist across the globe that would help in the investigation and trial of the war criminals of 1971. On the other hand some war crime researchers and leading freedom fighters think it would be better if international jurists, other experts and especially the United Nations help the Bangladesh government in the inquiry commission and trials as the UN has done in the case of many countries across the globe. But Justice Ghulam Rabbani thinks, that if we say the trial will be held under the supervision of the UN it will be a dangerous proposition because the country will have to surrender sovereignty. "We have the necessary Act namely the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act 1973," says Rabbani, "now the government will have to constitute one or more tribunals by appointing the members according to the terms of the Act." Shahriar Kabir, acting president of Ekatturer Ghatok Dalal Nirmul Committee (A Forum for secular Bangladesh) has similar views, "We expect the UN's role in trying the Pakistani war criminals but now we are more concerned about the trial of Bangladeshi war criminals." Hasan emphasises on the terms of references of the trial. "The UN can help us in many ways but terms of references should be formulated by our government considering our social, political and historic perspective." Regarding evidence, International Crimes (Tribunals) Act 1973 states -- "A Tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence; and it shall adopt and apply to the greatest possible extent expeditious and non-technical procedure, and may admit any evidence, including reports and photographs published in newspapers, periodicals and magazines, film and tape - recordings and other materials as may be tendered before it, which it deems to have probative value." Rules of evidence of the Act also says, "A Tribunal may receive in evidence any statement recorded by a magistrate or an Investigation Officer being a statement, made by any person, who at the time of trial, is dead or whose attendance cannot be procured without an amount of delay or expense which the tribunal considers unreasonable." "A Tribunal shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge but shall take judicial notice thereof." It continues, "A Tribunal shall take judicial notice of official governmental documents and reports of the United Nations and its subsidiary agencies or other international bodies including non-governmental organisations." Some war crime and legal experts say there is scope to categorise offences of war criminals of the Liberation War of Bangladesh as in the past few decades many new laws have been formulated, adding new universally accepted definitions of offences such as genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes against peace. The International Criminal Court and many other special tribunals in different countries have dealt with war crime and have defined offences in different categories. "We will have to check thoroughly who were involved with the crimes during our liberation war and under which category of the offences they fall," said Advocate Sultana Kamal. "We should proceed very carefully with a clear idea as the war criminals cannot evade justice due to the loopholes in laws," she added. Hasan points out the importance of involving the UN as it can play a key role in neutralising pressures from outside that may stand in the way of the process to try war criminals. Hasan said, "I came to know that when the caretaker government expressed their sincerity to the demand of trial of war criminals, some countries, even from the Middle East put pressure on the government not to try the war criminals." Khandker, elected law maker from the AL in last December's election and now planning minister, also a leader of the Sector Commanders' Forum, a newly formed organisation that came into the forefront during the caretaker rule with the demand for trial of war criminals, said that an inquiry commission can be set up under the tribunal and the commission would go through the existing evidence and will investigate further. Justice Rabbani says, "We already have the list of war criminals in Bangladesh and other necessary records and evidence. We have many documents with the names of the people who collaborated with the Pakistani occupation forces under different names including Razakar, Al-Badr and Al-Shams. Now the procedures should be started to try them." Hasan expressed his expectation in January that the new government would place the matter in the first session of the ninth parliament to initiate the process to try war criminals. He also expected an inquiry commission should be formed and be made functional by March and a tribunal for war crime should start functioning by the middle of this year "as we can have plenty of time to finish the long process of trial." Hasan's stance is clear about those war collaborators who did not directly carry out the crimes, rather masterminded them or assisted the Pak Army in committing them. "I think those who were not involved directly in the killing, rape and other war crimes but through provocation masterminded genocide and other crimes politically, must also be tried," he says. He adds that amending the constitution we can have provisions that those war criminals will not have any right to get involved with any organisation, politics and in any beneficiary post, but can only have voting rights as citizens. The government of independent Bangladesh in its first decision banned five communal outfits including Jamaat-e-Islami, which not only opposed the nation's independence but also actively helped Pakistani occupation forces commit genocide and other war crimes. After the country's independence in 1971, the first issue of newspapers of the new nation carried the government's decision to ban five communal parties on December 18. The Morning News ran the report that read: "The government of the peoples' republic of Bangla Desh (Bangladesh) has banned four communal parties with immediate effect. These four political parties are Muslim League and all its factions, Pakistan Democratic Party, Nezam-e-Islam and Jamat-e-Islami. In addition to these the government has also banned the Pakistan People's Party. The announcement was made by the Bangla Desh government in a radio broadcast." The banned parties including Jamaat were given the green light to start politics during the rule of late president Ziaur Rahman after the assassination of the nation's founding father Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975. In January 1972, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's government passed a law to try the collaborators and war criminals and set up 73 special tribunals, including 11 in Dhaka to try Razakar, Al-Badr and Al-Shams forces, defined as collaborators in the Act. A section of the political groups campaigned for the last three decades saying that the war criminals' trial issue had turned irrelevant with granting of a general amnesty to all by the then Awami League government. But the Collaborators Act, which was unveiled in a gazette notification on November 30, 1973, clearly states that none of the war criminals have been pardoned. "Those who were punished for or accused of rape, murder, attempt to murder or arson will not come under general amnesty under Section 1," reads Section 2 of the Act. Out of the 37,000 sent to jail on charges of collaboration, about 26,000 were freed following announcement of the general amnesty. Around 11,000 were behind bars when the government of Justice Sayem and General Zia repealed the Collaborators' Act on December 31, 1975. An appeal glut and release of criminals en masse followed the scrapping of the law. Anticipating sure defeat, the Pakistani occupation forces and their collaborators -- Razakar, Al-Badr and Al-Shams (mostly leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami and its student front Islami Chhatra Shangha) -- picked up leading Bangali intellectuals and professionals on that day and killed them en masse with a view to crippling the nation intellectually. War records show that Jamaat formed Razakar and Al-Badr forces to counter the freedom fighters. 'Razakar' was established by former Secretary General of Jamaat Moulana Abul Kalam Mohammad Yousuf, and 'Badr Bahini' including the Islami Chhatra Shangha members. Thousands of people still bear the brunt of war crimes by Jamaat and its student front (now known as Islami Chhatra Shibir), and some other groups such as Muslim League and Nizam-e Islami. Ali Ahsan Mohammad Mojahid, presently Jamaat's secretary general and then head of Al-Badr in Dhaka, led the killings of the intellectuals a couple of days before independence, according to numerous research works, academic papers, accounts of both victims and collaborators, publications including newspapers and secret documents of the Pakistani home department. Historical documents and newspapers published during and after the Liberation War show Matiur Rahman Nizami, the incumbent Aamir (chief) of Jamaat and the then president of Islami Chhatra Shangha, was also commander-in-chief of Al-Badr. He was quoted as saying on September 15, 1971 by Jamaat's mouthpiece the Daily Sangram: "Everyone of us should assume the role of a soldier of an Islamic country. To assist the poor and the oppressed, we must kill those who are engaged in war against Pakistan and Islam." Nizami's predecessor Golam Azam was the brain behind Jamaat's anti-liberation efforts. Immediately after independence Golam Azam, ex-Jamaat chief and many others like him fled to Pakistan and returned only after the brutal killing of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family in 1975.

However, some newspaper reports show how the collaborators were considered as a threat to sovereignty of the country even immediately after the liberation. Bangla national daily The Azad on January 20, 1972 published the lead story titled, “Al-Badr and Jamaat goons are carrying out subversive activities from their hiding places,” and “Liberty is still at stake” (Al-Badr O Jamaater Pandara Ga Dhaka Die Nashokota-mulok Tatporota Chalachhe, Swadhinata Rokkhar Bipod Ekhono Kateni)." Some infamous collaborators currently live abroad, for instance, Chowdhury Moeen-uddin who was 'operation in charge' of the killings of intellectuals, lives in London. The newspapers published a report after December 1971 with a photograph of Moeenuddin, titled, "Absconding Al-Badr gangster." A similar report published in a Bangla national Daily Purbadesh on January 13, 1972 with a photograph of Ashrafu-zzaman Khan, titled, "Nab the butcher of intellectual killings." Ashrafuzzaman reportedly lives in the United States. During the nine-month bloody liberation war in 1971, Pakistani occupation forces and their Bangladeshi collaborators committed genocide and war crimes that left three million people killed and a quarter million women violated, let alone the planned elimination of the best Bangali brains of the soil on December 14, 1971. Demands for trial of war criminals is the oldest issue of the country, linked to the birth of Bangladesh. Reports in the newspapers published immediately after the liberation gives proof of the peoples' cry for justice. On December 19, 1971, Daily Ittefaq carried a banner headline," Golden Bangla sees the worst massacre in human history (in Bangla--Sonar Banglai Manobetihasher Nrishong-shotomo Hottyajoggo). "Bangabandhu said that if Hitler lived today even he would have been ashamed to see what happened in Bengal," Bangladesh Observer reported on January 15, 1972. Former German ruler Adolph Hitler led the Nazi Party, infamous for genocide and war crimes committed during the Second World War. On the same issue, the English daily published a report titled, "War criminals will not go unpunished." The report said, "Prime Minister Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman held out an assurance that the war criminals will not go unpunished because people must have a feeling that justice was done." The same newspaper in its issue of January 22, 1972 published a report titled, "Mass Killers will be tried: Mujib, We want peace." The report was on a team of World Peace Council's call on to the then Prime Minister Sheikh Mujib.

The report reads: "The Prime Minister (Sheikh Mujib) was of the opinion that the United Nations should come forward and take the initiative in instituting a tribunal to go into the genocide of civil population. Such a step was necessary, he emphasised because many of those who had taken active part in massacres or were responsible for planning it, were now living outside the jurisdiction of Bangladesh Governemnt. For the sake of justice those people should also be brought to book, he said..." After repealing the Collaborators' Act in December, 1975 the demand for the trial of war criminals lay dormant in the hearts of Bangladeshis and was rekindled by the historic mass movement by Shaheed Janani Jahanara Imam in the 90s. Shyamoli Nasrin Chowdhury, widow of Martyr Dr Alim Chowdhury says, " I want to believe this time that war criminals would be tried. I am ready to give my statement as a witness and victim when the special tribunal starts functioning. I have been waiting for the last 37 years for this most desired day." "I believe the trial of war criminals of Bangladesh's liberation war is not only the responsibility of our state, people, country and government. It is a prerequisite to create a just and civilised society. Those who have committed the worst crimes in this nation's history must be tried for the sake of humanity," Sultana Kamal opines. Sultana says, "Following the election result now, it is evident that the issue of the trial of the war criminals has unanimous people's support. This issue played a vital role for the over-whelming victory of Awami League. So there is no scope to have an excuse this time in failing to try war criminals." Ferdousi says, "It is disgraceful for us when we claim ourselves to be civilised without trying the war criminals. This issue (war crime) has shattered our lives. I hope we do not have to continue the movement for the trial of war criminals any further; this time we expect it to come to an end with the trial of the war criminals." Trying war criminals has been one of the top five election pledges of the present government. And even after wining the election and forming the government, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and many of her cabinet colleagues throughout the last year reiterated their stance regarding the issue. The parliament in its first session passed a resolution unanimously for trying the war criminals following a proposal placed by a ruling party lawmaker before the House. In its first budget in June the cabinet also approved Tk 10 crore as block allocation for the much-awaited trial of war criminals. The government also amended the International (Crimes) Tribunal Act 1973 to make it up to date.

Despite all this, no major progress has taken place with regards to starting the trial. It has caused deep frustration and concern among the leaders of different forums of freedom fighters, intellectuals, academicians, human rights activists, war victims, researchers and experts on war crimes of 1971. The government's dilly dallying has not been well documented, but where do we go from here. Some statements made by a few ruling party ministers also created confusion and suspicion about the government's outlook towards the issue. Some of them denied having any international or foreign pressure to try war criminals, while some others just opposed it. Some ministers even said that they were all set to start the process of the trial, they even declared a date for announcing the investigation and prosecution cell to deal with the matter. But eight months after that announcement the government has yet to take any concrete measures. "As long as a special tribunal is not formed to try the war criminals where the state would be complainant, we cannot say the trial process has started," Freedom fighter, former army chief and leader of the Sector Commanders' Forum Lt. Gen (retd) Harun Ur Rashid observed. In fact the way the government dealt with the issue of the trials of war criminals in its first year, makes one feel that nation has listened to the government and is now waiting for words to turn into action On the flip side, different socio cultural organisations and forums, which were very active demanding the trial of war criminals when Awami League was in opposition, became less active in their movement after Awami league assumed power. Some leaders try to justify their current lack of enthusiasm by saying that they want to give more time to the government to start trial process so that they are well prepared as they (the government) had to face some extraordinary situations such as the BDR mutiny, just a month after taking to office Besides that the completion of the trial of Bangabandhu murder case was also a very big challenge for this government. Though the trial has been completed, the execution of the killers of Bangabandhu is now a major task for the government. But it seems like situations and challenges -- like the continued threats on Hasina, pressure on her from inside and outside the country not to deal war crime after 38 years of independence, pressure from the international community to ensure the war crimes trials are performed in an internationally accepted way, fighting militancy, ensuring trial of other major terror attacks and impending threats of more attacks -- has made it more complicated for the government to go forward with the expected speed to ensure the most popular demand for justice. Times may be tough, but hope and confidence are sky after the nation finally got justice for the killing of Bangabandhu. The government must use this as a catalyst to finally try war criminals that have lived without the fear of prosecution. There has never been a better time for justice to be delivered. Julfikar Ali Manik is a Senior Reporter of The Daily Star. He has received numerous awards for his investigative journalism as well as the Hasna Hena Qadir Smriti Award for the best report on the Liberation War. |