Inside

|

When It Also Happens At Home Hana Shams Ahmed talks to Sara Hossain about domestic violence

In December of last year, a case was brought to court by 33-year-old Dr. Humayra Abedin, with the help of human rights organisation Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), against her own family, for confining her against her will. She had come to Dhaka in August of that year after being told that her mother was seriously ill. As soon as she arrived home, her parents hid her passport and plane ticket and held her captive. She was forced to take mood stabilisers and anti-psychotic drugs until she confirmed that she would not be returning to the UK, and would give up her job and disassociate herself from everybody she knew there. On November 14 she was allegedly forced to get married to someone against her will. There were repeated attempts on the part of her parents to not comply with court orders. They only responded after the court said it would hold them in contempt if they failed to show up. They kept claiming that Humayra was mentally ill therefore unable to appear. After a fierce legal battle and after the High Court in England also passed orders requesting the co-operation of the Bangladesh judiciary and the authorities, her parents finally allowed Humayra to come to the Bangladesh High Court. Two judges interviewed Humayra in person and ordered her to be released and she immediately returned to the UK later that month. Unfortunately this is not a unique case. What was different here was the fact that the woman came from an economically liberated background, where such things as forced confinement or forced marriage are much less common. But it's also perhaps because of her economic/social background that the amount of violence perpetrated on her became public. Other stories of family violence to force younger women to comply to things against their will usually stays within the four walls of the home. There are many other cases of psychological torment carried out by close family members, which are not even recognised by the present legal structure. Cruelty from in-laws, bullying by parents and older family members, and other forms of family intimidation may not necessarily require legal redress, but the victim may require intervention of a third party. According to ASK there were only 608 reported cases of domestic violence in 2008.1 But most of these cases never make it to any police station, so the statistics from ASK are only a section of the reported cases. In 2001 World Health Organization (WHO) carried out a cross-sectional survey2 of 1,603 women in Dhaka and 1,527 women in the rural area of Matlab. 40 percent of the women in Dhaka and 42 percent of those in Matlab reported physical violence by their husbands. A potential draft law on domestic violence was prepared by the Law Commission in 2006.3 Various organisations who've worked with women and girls looked at the problems with the legal system and the difficulties with accessing remedies, and specifically the difficulties with getting protection for women and girls who were being subjected to continuous acts of violence. ASK and the Bangladesh National Women Lawyers' Association (BNWLA) drafted separate Domestic Violence Bills. Mahila Parishad also worked on proposed reforms of all the family laws -- to state clear ground for divorce, separation etc in cases of domestic violence. Different organisations have worked for many years on supporting women who had undergone different aspects of domestic violence. A group of about 35 organisations, the Coalition of Voices against Domestic Violence, then came together to review the Law Commission's proposed Domestic Violence Act. They have suggested detailed changes, and already submitted their proposals for consideration to the Ministry of Women's and Children's Affairs. Sara Hossain, who fought the case for Dr. Humayra Abedin and who is also an active member of ASK, speaks to Forum's Hana Shams Ahmed about the importance of, and need for, such an act.

HSA: There already are various criminal laws that can be used to protect a woman from violence against her. Why do we need a separate Domestic Violence Act? There's also an existing special law on violence against women, the Nari Nirjaton Ain 2000. But this only addresses cases of domestic violence in a very limited way. We have focused a lot on stranger violence, we haven't really focused on violence that comes from a member of the family. These are also very difficult to confront in the society which is very family-oriented. For example, for any acts of violence, including the demand for dowry, you can prosecute under that law. Or if such acts involve acid throwing, then you can prosecute under that law. You can have them [the perpetrators] tried, punished, and imprisoned. If the form of domestic violence is for example forcible sexual relations with an under-aged bride (16 years old or under) then a case of marital rape can be brought against the husband. But these are very limited kinds of possibilities that exist -- also, all are about taking the perpetrator to court and prosecuting them. They don't really deal with the issues of immediate protection or security for the victim or all the issues that arise after the incident of violence. It does not address everyday form of domestic violence. According to the research in this area, what women want is immediate safety and security, and an end to the violence, and then accompanying that, an opportunity to work out and resolve other issues, for example, child custody or maintenance expenses. The proposed law tries to address all these issues. Most importantly, it defines domestic violence as violence that's not just between spouses but between family members. It's a very common misunderstanding that domestic violence is limited to that which occurs in marital relationships. This law proposes a definition that it is not just about violence on a wife by a husband but by any other family member. It also incorporates the idea of violence or intimidation by parents on children, the kind of violence, which is sadly becoming increasingly recognised as occurring in our society.

The second thing about the law proposes certain new remedies. If a complaint about domestic violence is made against somebody, the court may make an order to keep that person out of the home for a certain specified period of time, so that he cannot commit a violent act inside the home (an exclusion order). Another proposal is for the court to grant an occupation order, allowing the person who is the victim to occupy their home. This would be a great difference from the current situation where it is the victim who is usually forced to flee her own home in search of shelter. There are other orders that are proposed, for example, protection orders, i.e. the person who has been violent must not approach this person, must not come near this person who is a victim, in any public place either. The law also proposes that if any of these orders are violated by the person who is being violent then they could be liable to arrest. It defines domestic violence as including psychological violence, physical violence, sexual violence, and economic violence. It puts the whole emphasis on protecting the interest of the victim. This law gives a very broad definition of "violence." In many cases of domestic violence women are saying that they don't necessarily want the relationship to end, but they want the violence to stop. The law seeks to address this and focuses on ending the violence and protecting the victim. We have seen in many cases involving family members that the police are reluctant to take up a case. They also try to do the work of an informal arbiter, by trying to convince victims not to file a case because it involves members of the family and they think that such cases should be settled in their own homes instead of taking it to court. Even when a case is taken up, it turns into a long-winding process and at the end is not fruitful for the victim. How can this problem be solved?

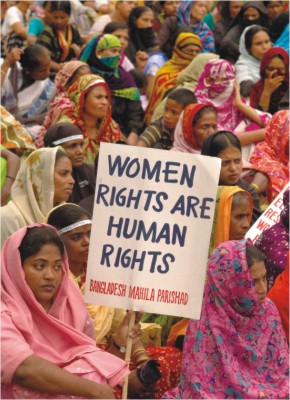

I believe that these efforts should be directed towards those who are in charge of applying the law. There should be clear guidelines, a checklist, of what a police officer has to do when interviewing a victim or a witness of domestic violence. In other countries this checklist has worked very well -- that when a woman has come in to make a complaint, the police officer concerned has a clear duty to primarily ensure her security and then to conduct her interview with sensitivity and with an understanding of the nature of violence that has been undergone. It would be very helpful if those kinds of checklists or guidelines could be prepared by the relevant ministry/authority, particularly by the home ministry, the judiciary and by the police, and if their officers can be clearly trained on the content of such checklists and how to apply them. The existing law already criminalises many acts that routinely occur in cases of domestic violence. But because some of the acts are carried out by a close family member, the police don't take it seriously and won't treat it as a criminal offence. If the police are sensitised then there will be a difference in trying to make the existing law work more effectively at the same time putting in place through the new law the protections for victims/survivors that we don't have under the existing law. The Coalition of Voices against Domestic Violence has made some recommendations in this regard. First, there should be awareness among the police, health providers, judges and court officers. Secondly there must be a major awareness raising campaign for people who may need the protection of the law and for those who are responsible for enforcing it. Thirdly, we need changes in law to make it work more effectively. And fourthly, we need to put into place the new law which will provide protective remedies for victims/survivors. The draft law on domestic violence was prepared by the Law Commission four years ago, but the government did not take it forward at that time. However, with the coalition, we have given a copy of the revised draft of this law to the ministry of women and children affairs and prior to that the ministry itself held a meeting with the coalition committing to work on this draft. Some groups like Bangladesh Mahila Parishod have also lobbied for a change in the law with the Law Ministry. You talked about psychological violence, which is a big part of what occurs in cases of domestic violence. How does one go about proving such acts of violence in a court? Incidents like this could be proved by expert testimony from a psychologist explaining what's happened to the woman concerned. We do now have trained counsellors and psychologists in Bangladesh, who are aware of how domestic violence manifests itself on a person and what the impact can be on the victim. Humayra Abedin's case demonstrates something very important. It is assumed that domestic violence is only perpetrated on victims who are from an economically/socially disadvantaged group. But it is certainly not so. The experience of most people who have worked with victims of domestic violence is very different, that in fact survivors of domestic violence come in all shapes, sizes, classes, and from all kinds of community and class backgrounds. It's not at all limited to just people who live in poverty or those who do not have access to other resources but even people who are among the most wealthy and most privileged in society can and unfortunately do become victims of domestic violence. The stigma on speaking out against domestic violence means that those from the most privileged classes are often most reluctant to talk about it. Because the notion of "honour" (ijjot) is so prevalent in the middle class and much beyond that, it's much harder for them to talk about what happened to them.

Women are dealt a double blow in cases of domestic violence where in-laws are concerned. Sometimes when a woman has trouble with their in-laws, not only is it after a long time that she comes out and talks about it with her own family but even when she does talk to her own family they try to convince her to "bear the pain" and not make such issues public. Violence -- wherever it occurs, including within the family, need to be challenged. There's a tendency to not talk about things that happen within the family, outside the family. The family is seen as a sealed unit. But more people have begun talking about such issues than ever before, as we increasingly recognise that violence is violence no matter where it occurs or who the perpetrator is. 1. "Human Rights in Bangladesh," Ain o Salish Kendra, 2008. Hana Shams Ahmed is Assistant Editors Forum. |

It is for us to recognise that the roots of domestic violence and spousal violence lie in our own cultural and social attitudes. The whole idea that most of us have of a family, and the idea that is prevalent in our culture is the exact opposite of anything that could be considered to be a democratic structure -- you are expected never to argue with the person who is the head of the house who is usually either the father or the husband. And the assumption is that you need to listen to that person at all costs. Those kinds of notions of what a proper family should be negate the possibility of recognising that people within the family have rights, and responsibilities, vis-à-vis each other.

It is for us to recognise that the roots of domestic violence and spousal violence lie in our own cultural and social attitudes. The whole idea that most of us have of a family, and the idea that is prevalent in our culture is the exact opposite of anything that could be considered to be a democratic structure -- you are expected never to argue with the person who is the head of the house who is usually either the father or the husband. And the assumption is that you need to listen to that person at all costs. Those kinds of notions of what a proper family should be negate the possibility of recognising that people within the family have rights, and responsibilities, vis-à-vis each other.