Inside

Original Forum Editorial |

| You are What You Study--Ahmed A. Azad |

| Back to the Drawing Board-Abdus Sattar Molla |

| Going Digital-- Swapan Kumar Gayen |

Treat the Water Right-- Mubarak Ahmed Khan

|

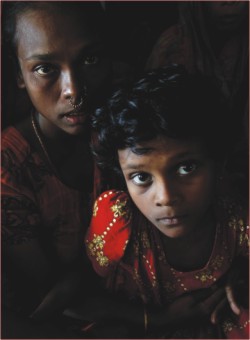

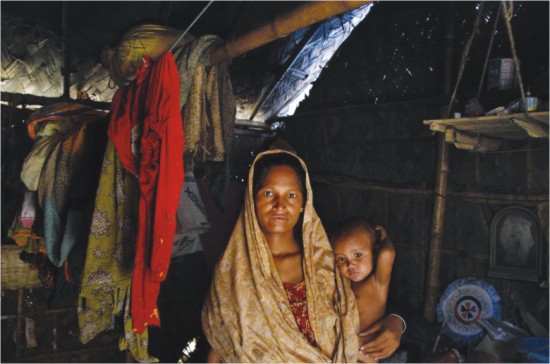

| Photo Feature: Mughli-The Lonely Mother--Altaf Qadri |

| Microcredit 2.0--Mridul Chowdhury and Jyoti Rahman |

| Miskins, Misfits and Mothers-- Farah Mehreen Ahmad |

| Growing Pains-- Mustafizur Rahman |

| Jessore Days-- Ziauddin Choudhury |

| Manslaughter-- Shamsuddin Ahmed |

Miskins, Misfits and Mothers Farah Mehreen Ahmad asks why we always look the other way Zehal-e miskin makun taghaful, (Do not overlook my misery -- original by Hazrat Amir Khusrau, translation by “Unknown” Borsha* did not know she had no right to fall in love. In fact, she did not even know, she had

no right to be. She was one of the many floating prostitutes of a mazaar area, who existed, but not really. She was a fool who made the mistake of falling in love, an imbecile who forgot she was not a human-being, and tricked herself into believing the promises her customer-turned-lover made of marrying her. She was a dweller of a mazaar, the place where hundreds of people flock on a weekly basis to conduct wish-fulfilling rituals. And apparently they work. So why wouldn't her wishes come true when she lived amidst all that magic? She forgot magic wasn't for her either. So her eyes were pulled out, and she was killed by her lover in the Shaheed Minar area. An unfit awakening for fitness freaks who workout there early in the morning and discovered her dead body dangling from a tree. She needed to exist to cater to our needs, but she had no right to exist. Her story is the perfect example of filth permeating through what we would like to believe is our holy and untainted society. Not the filth we accuse her of diffusing, but the filth we create and conveniently shove under the rug. Borsha lived her life to hone our selfishness, and died at the hands of our nonchalant cowardice. One for All, But None for One “Slaves” may seem like an exaggerated way of labelling them because as commercial sex workers, they do in theory, get paid. But given how invisible our society has rendered them, when a customer refuses to pay for a service, there really is no agency or organization that will fight on their behalf to get them their remuneration. And it's not as if their customers just don't pay and leave, they are often subjected to unbelievable amounts of violence for asking for their dues. The state of the floating sex workers -- battered, beaten, and banished -- brings to question our sense of community. That we live in a community and are responsible for each other only seems to be realized when we want to quench our thirst for butting into other people's businesses. But when it comes to fighting, to protecting, there is no one. How is it that 15 year old Laila* feels the need to tie her infant of several weeks around her waist while napping, that even in the afternoon when the mazaar premises are abuzz with people, she wakes up to find somebody is trying to cut the rope to steal her baby? Why is it that they are forcefully taken away and raped at anybody's will and no one in the vicinity steps up or steps in? Babies being stolen and babies being bought are common practices within these premises. When I asked Laila why babies are sold, she admitted that just this morning, she sold an abandoned infant to a childless woman who came to the mazaar to buy a baby. She said in the future she might even consider selling her baby to a rich family so at least she can feel safe about him being free from the kind of life she has to lead. I don't know if she is that naïve or if she was pretending to be so, but we all know that not all babies go to fill voids in the laps of childless parents. Especially not the stolen ones. They go on to become camel jockeys, involuntary organ donors, sex slaves, heroin money…Their mothers never get a chance to warn them against taking candy from strangers; they become the currency for strangers' candy. Razia* said she would be better off giving her baby away because if he ever asks her about his father, she would not know what to say. "Mukh rakhbo koi?" is not a question on the lips of just this one person. The way we have laid out our social infrastructure is phenomenal. The state and we, fail to protect women from falling into communities we go on to stigmatize later. We fail to dignify them as women and mothers. We deprive mothers of their right to raise their children, and children of the right to be raised by their mothers. We push them into a hole, step inside and use them as we need and please, and climb out to point fingers at them. We really give them no spaces for their faces. Mukh raakhbe koi? As our sense of community degenerates at a fast pace, we have found a stupendous way of safeguarding the undeserving and relaying responsibility onto unknown actors. When my friend got into a chain accident very recently, a motorbike rider who was most hurt in that accident, and was just a victim of the situation, was blackmailed by the investigating officer into paying a bribe or else he would have filed a case against him. What were the hospital personnel doing while this was going on? How is it that another friend gets mugged and dragged along the street by the infamous muggers-in-cars on the evening before Eid in a busy shopping area, and everyone is a spectator? It is because perpetrators know that everyone is too scared or nonchalant to step in, or is relying on someone else to do it, that they gather the courage to act in public spaces. There really is no difference between an empty, dark alley and a crowded street anymore. We do however, have an amusing culture of redundant compensation. My first field trip after I joined BRAC was to Mymensingh. Between field visits, the local staff took me and two other colleagues to the Muktagachha Palace. Well now hardly a palace, but more a skeleton of a once palace. Its last inhabitant had fled during partition, following which the locals came to strip the place of all things of value. So what we saw was a spooky, naked frame. The layout of the place was quite mind-boggling for me. The jalsaghar area in particular was eerie. A huge space in the centre, cabins for baijis at its foot, a puja mandap by its head, the <>zamindar's<> main bedroom to its left, and torture cells for fathers who refused to send their virgin daughters to the zamindar to its right. Between the jalsaghar and the torture cells was a well with a chopper installed, where dead bodies would be dumped to be cut up and transported to the river to which the well was connected. I could go on to draw metaphoric parallels between then and now, but I am sure you can read between the lines and do that yourself. Coming back to the culture of compensation, the last zamindar who inhabited the palace was allegedly the cruellest of all "jodio uni shikkhar jonno besh kichhu kore gese". The consumers for Muktagachhar monda were he and his family, his favourite elephant and his Baijis. Anyone else having or even trying to have those mondas was penalized. For some reason, feeding his Baiji mondas reminded me of people who feed beggars on Fridays, Borsha's lover who distributed jilapis among all homeless people in the mazaar after killing her, dancers on stage compensating for a lack of steps by waving bright-coloured fabric, corrupt officers who distribute food, clothing and other forms of charity on Fridays to partially whiten their black money, cook show hosts making up for their inability to make clever comments about the food by repeating "bachchara-o khub pochondo korbe," writers' over-usage of "and then s/he lit a cigarette/ took a long drag," TV dramas filling up the space left by lack of crafty dialogues with “ei na maane, bolchhilam ki … yeh … maaaannneee … umm yeh aarki…” Excuse me, what? Then there are more brutal compensations, compromises rather -- these mothers selling their children with hope for a better future for them, cleaner identity; that one woman who took her 3 year old son to her slum's goon-squad to pour acid onto one of his arms so he can show that off and make some money. "Dui haath diya ki korbo, jodi pet-a bhaat na thake?" Putting and Pudding Though intrinsically and partially legally criminalized, it has always been (even if implicitly) acknowledged to be a tolerable and often relieving counter to emergence and increase of sex crimes. As much as there is an unscrupulous amount of moral policing surrounding prostitution and even porn, studies have shown that they have to a large extent, served as alternate and alternative 'solutions' to rape and other forms of harassment. (But let's also acknowledge that the latter sometimes instigates harassment too.) Minus the need-fulfilment function which has been a consistent consumption for all classes within a society, prostitution has also been nuanced enough to make status statements. Tawaifs and Baijis were the 'shaan' of the aristocracy back in the day. I suppose a contemporary parallel can be elite escorts, though this niche is more subdued and barely flaunted. Dear bonedi poribaars, khandaani ghors, shikkhito Bangalis and bhodrolok shomaj, I know you would like me to believe that theirs is a parallel reality so far removed from yours that the two will never intersect. I agree. But only because just from one fragmented brush with a small segment of theirs, and a lifelong membership in yours, has made me aware of how you and I will never be able to fathom how they survive in theirs. Yes, we will never intersect. Funny though, since even from within separate peripheries we feed into each other's realities. Even funnier is how everywhere the ones below stand to cater to needs of the ones above. As much as 'gentlemen' would like us to believe consumers of commercial sex are rickshawallahs, truck-drivers, durwans, day-labourers, goons and the likes, the fact that the prostitution market itself is so nuanced and classified, is evidence enough that there are consumers in every strata of society. This is not a recent paradigm shift or stretch, it's just a paradigm exposed. For simplicity's sake let's assume that the clientele of the homeless floating prostitutes in the Mirpur and High Court mazaar areas are restricted to aforementioned local goons, slum-dwellers, rickshaw-pullers, bus and truck-drivers and homeless men in the vicinity, and not people of higher classes who frequent and inhabit the area, but who are the prostitutes frequenting and residing in mid-range apartments and second-tier hotels for? So if the girls I see standing on street corners of Gulshan-Banani-Baridhara tri-state area only cater to drivers, durwans, rickshaw-pullers, etc. why do they approach SUVs when they pause for even a brief moment? Don't they know their clientele? And why have I seen 'those bad type of women' in 5 star hotels? That 15 yr old girl in a bright red t-shirt, skinny jeans, obnoxious and messy make-up, poorly bleached hair and a severely underweight body, who walked into the lobby with her colleagues -- straight into the gluttonous eyes of our fellow brothers -- why was she there? Just for the foreigners? What about the two giggly ones in the bathroom of another hotel, fixing their make-up and teasing each other about how many directions each can bend in? It's time to fold up and throw away the scaffold. Class can be a shield, but not a mask. So please, do continue to keep your eyes shut, but do not assume you're invisible as a result. Comedy of Terrors Yes it is infuriating, ridiculous, stupid, despicable and anything else you are probably (hopefully) muttering. Those kids probably found it amusing to brutally brush against these forbidden females and found it a sufficient scope to power-trip at the expense of their powerlessness. They also thought, while having fun they were teaching 'bad people involved in bad things a good lesson.' Of course the kids are to bear a hefty chunk of the brunt of the rage this has invoked, but let's not forget that this attitude is not innovated, but rather inherited -- be it from their parents, extended family or greater society. Everybody is out to play prophet; to denounce and penalize whoever and whatever is contaminating their pristine surroundings in their own little way. Prostitution is dirty, and we janitors have set out to clean with whatever props we have at hand (read eggs). What is most frustrating is that while writing pieces like this, there are juvenile moments when the obvious needs to be stated. What makes prostitution “dirty” is the process in which it operates. It is the deceit, the victimization, the abuse, the exploitation, the insecurity, the vulnerability and the exclusion of the prostitutes that accumulate to the filth we so shamelessly take stabs at. Our society has become a network of cheeky monkeys standing on play … I mean high … moral grounds and slathering dirt on these people and their profession we either pushed them into, or failed to protect them from falling into. Then we defiantly turn around, point, cringe and call it 'dirty'. A naïve bluff of calling a spade, spade; a perverted bluff of calling the killed, killers. But I guess it's ok to treat these 'maagis' like dirt. They ain't no Anarkali or Umrao Jaan. If you can't use them to make ostentatious statements, wring them and make pretentious judgements. Zakia*, approximately 20 now, was sent off to the city to find work. After working as domestic help for a while, she could not bear the torture inflicted upon her by her employers at the time, so she fled. She came to seek refuge in the mazaar, and as per ritual, was gang-raped by the local goon-squad (syndicate) and inducted into the world of prostitution. She once went back to her village, but was disowned by her family because of the kind of work she was involved with. The family could not bear that their economic crutch had now morphed into a moral burden. She returned to Dhaka to the same place and same life. Tara's* story is similar. After she and her baby were abandoned by her husband, she was tricked into the trade by a phoney well-wisher who promised to set her up with domestic work. She left her baby with her family back home. The 'agent' sold her to a brothel in Faridpur. After a while she ran away from there and went back home, only to face rejection. She then came to Dhaka in search of work, and before she knew it, the woman who was helping her find work, led her to the mazaar area. In a jiffy, she went from being an organized slave to a floating slave.

Theirs are not the only stories. There are many like them pushed into the quicksand of this isolated world, and kept there to make us look clean. It is as if they cold-shouldered us and walked into that life, when in fact it is the double whammies from four different directions state, which failed to protect them from falling into this profession and cannot make up its mind about whether to criminalize or legitimize them ; family, which cannot bear their economic or moral burdens; extended society, which is too busy acting clean, playing under the sheets and extending concern about 'society's moral fabric'; and umbrellas of religious credo, which don't accept them unless it's time to act like basket-cases and make charity cases out of them to earn tickets to personal mission fulfilments (read food or money distribution for 'mannats') and heaven - that keep them quarantined. It's how Rokeya* put it, "poolisher dhakkaw khawon laage, mainsher mair o khawon laage, baap-maa'r gaali-o khawon laage. Eida ki kono mainsher jaga?" It's like that Mollah Nasiruddin story. Remember the one where the king went hunting one day and ran into Mollah in the forest? Declaring him an 'opoya,' (bad omen) the king summoned for Mollah to be subjected to 20 whip-lashes. His hunting trip that day however, turned out to be stupendous. When the king called in Mollah to apologize, the latter said, "Hujur, you call me an 'opoya,' but you see my face and your hunting goes well, but I see yours, and I get a beating. Who is the real 'opoya' here?” Sages and Savages We talk about giving business and development interventions a "human face," but in that process we neglect to acknowledge, let alone dignify, the ones suffering the most at the hands of inhumanity. Typically risk-averse, we are so busy playing safe; so absorbed in generating multifarious responses to mono-dimensional issues; so caught up with feeling good and being right, we forget about doing right. "Human face" will not come with discussing Amartya Sen's Capabilities Approach over a glass of white wine or devising a better, more-inclusive microfinance system that can cut through/penetrate and capture the ones furthest down the socio-economic echelon, nor does it come with reviving 1952 and 1971 sentiments for the purpose of boosting SIM card sales. In these attempts, we are not giving a "human face," we are just wearing a human mask. To assume that face, we need to face the faces we forcefully keep buried; to shed our prophet-skins and expose our own faces first.

As I was speaking to these women, I was jostled by a million thoughts coming at me from every direction. I was thinking of what kind of rehabilitation measures would be most effective, how our society needs to step up and seek redemption by assuming responsibility, and an overall need for the revival of humanity. But I was all of a sudden interrupted by Tara*: "deen raat jai koshto houk na ken Apa, chawa khali ektai, ghoom-ta jani shanti moton ghoomaite pari. Raate bela mazaar a ek ghor a amra 250 jon chapachapi koira thaki. Tao ashpasher polapain aisha jalaye. Khali ekta ghor koira den Apa, aar kono chawa nai." Jotsna,*who hadn't uttered a word the whole time smiled and said, "Manusher jonno koy manusher jibon, kachhe ashle kaachkola."

Farah Mehreen Ahmad works for BRAC and is also a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective. |