Inside

|

The Polluter Pays Principle Who should foot the bill when the environment is damaged asks Shahpar Selim The last few months has seen startling news headlines on river pollution and a momentous High Court Directive given on June 25, 2009 to save ecologically critical rivers surrounding Dhaka. Another High Court directive was given to the tannery industry to expedite its relocation to Savar, where they will be allowed to operate using Central Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs) to reduce the impact of their effluents on surrounding water bodies. More and more, we see an emphasis on making the polluters accountable for the ecological damage they are causing to themselves and to their future generations. Indeed, holding the current economic drivers accountable for environmental damage is also at the heart of Bangladesh's climate change demands. However, looking for environmental responsibility as a piecemeal initiative (e.g. separate HC directives noted above) may be a beginning, but we need to think of it within a broader framework. It is time Bangladesh addresses pollution management, financing and cost recovery by rethinking the current modes of operation employed by the regulatory stakeholders in line with the opportunities presented within the full cost recovery options using polluter and user pays principles. Background to environmental costs and the Polluter Pays Principle (PPP) The PPP is not new for Bangladesh: PPP was first mentioned in the 1972 Stockholm Declaration Recommendation by the OECD Council on Guiding Principles concerning International Economic Aspects of Environmental Policies. Bangladesh is a signatory to the Rio Declaration, which clearly enunciates the PPP via Principle 16, "National authorities should endeavor to promote the internalisation of environmental costs and the use of economic instruments, taking into account the approach that the polluter should, in principle, bear the cost of pollution, with due regard to the public interest and without distorting international trade and investment." The PPP is further mentioned in Agenda 21 and the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) Johannesburg Plan of Implementation (Earth Summit 2002). The PPP is also the cornerstone of European Community Environmental Policy. The Indian government has embraced PPP in its 11th Five Year Plan in 2006, while Thailand adopted the PPP in 1992's Environmental Act B.E. 2535 and in its' environmental conservation strategies of the 8th Economic and Social Development Plan. PPP is also the cornerstone of international environmental law covering trans-boundary pollution issues. However, recently the PPP has evolved into different strands, including the extended or strong PPP which calculates for the costs related to accidental pollution.

Consequently, the GoB has embraced the PPP in the spirit of fault based liability in its environmental laws. The 1995 Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act, explicitly says in para 7, "If it appears to the Director General that any act or omission of a person is causing or has caused, directly or indirectly, injury to the ecosystem or to a person or group of persons, the Director General may determine the compensation and direct the firstly mentioned person to pay it and in an appropriate case also direct him to take corrective measures, or may direct the person to take both the measures; and that person shall be bound to comply with the direction." Water pollution in Bangladesh is created by polluters' free riding behaviour (polluting industries continue to operate flouting all national regulation on water pollution, and produce large quantities of untreated effluents that go on to damage peoples' health and the ecology and the polluter never pays for damages). The main Bangladeshi laws regulating pollution by the DoE has PPP in spirit, as we saw earlier, but regulation of water pollution is also influenced by the National Policy for Safe Water Supply and Sanitation 1998 (NPSWS&S) and the National Water Policy (NWP). These policies have the over arching goal of providing access to safe drinking (and cooking) water and sanitation services at an affordable cost but PPP is not part of these policies. Pollution control in Bangladesh (solid, liquid and air) is regulated chiefly by the Ministry of Environment and Forest's (MoEF) Department of Environment (DoE), with additional and parallel responsibilities of water supply and sanitation borne by the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives (MoLGRD&C). The MoLGRD&C's Local Government Division (LGD) is responsible for policy making, planning, financial mobilisation and allocations impacting water resource management (where pollution related problems make their presence felt significantly). The Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) is responsible for planning, designing and implementing water supply and sanitation in rural and urban areas (except where WASA is operational, namely in Dhaka and Chittagong). The Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) undertakes water and sanitation related activities in municipalities (pouroshobhas) and liaise with various City Corporations. City Corporations are responsible for drainage, solid waste management, and maintenance of water supply and sanitation systems installed by DPHE or LGED. Dhaka WASA is responsible for water supply and sewerage, while Chittagong WASA deals only with water supply. The pouroshobhas take care of water supply, solid waste management and sanitation, but most rely on DPHE or LGED for design and construction. While these agencies collect various fees (e.g. environmental clearance certification fees (DoE), water supply and sanitation bills (DWASA) etc.), the revenue generated is not set aside for pollution management in any way, and the revenue amounts are not calculated keeping in mind ecological costs -- which effectively means that the various fees are totally non-reflective of PPP. For example, DWASA charges taka 5.50/1000 litres for domestic users, and taka 18.25 for commercial and industrial users (these rates are applicable for metered users; non metered users pay under a different pricing scheme). If these users subscribe to DWASA's sewerage system, then they pay double of what their water meter shows at the end of the month. Therefore, WASA customers are charged according to how much water they use, and "rent" for using the sewerage system. This does not reflect the ecological damage caused once that water is polluted and returned to the water bodies, nor does it reflect the human suffering caused (and loss of valuable earning for day wage earners due to missed work days) due to waterborne diseases. DWASA does not charge the industrial users for the volume of effluents discharged into the sewerage; the DoE does not charge industries for their pollution loads either (e.g. charging factories for how toxic their polluted water is, how expensive it would be to treat this toxic water for the government agencies or how many litres of polluted water they are creating per day).

Calculating pollution management costs in Bangladesh Consequently, at present there is no integrated or official process for planning capital expenditures for water, air or solid waste pollution management. Capital purchases of pollution control equipment are not distinguishable, nor are cost recovery structures. Recurrent costs are borne through yearly budgets allocated to these agencies via general revenues. The regulators and the public (as users and as civil society) have limited choice over or information about the most cost effective types or levels of pollution prevention/abatement that is appropriate for Bangladesh. The absence of reliable data on these parameters, plus the absence of agreed upon pollution prevention/abatement frameworks protective of Bangladesh's ecology and citizens, is resulting in an non-monitised and unaccounted environmental deficit. At this juncture of environmental policymaking in Bangladesh, there is an important opportunity to fine tune current systems in line with international best-practice thinking that the current government could consider, further fulfilling their election mandate on protecting the rivers and abating pollution. Full cost recovery and polluter and user pays principle PPP Driven Pollution Management Model: There needs to be a reassessment of current pollution management thinking, with a redefinition of objectives, and mechanisms (legal, institutional and budgetary) for achieving those objectives. Existing policy on pollution management financing may be revised upwards to what may be called an "intermediate" model meaning that significant health and environmental benefits will be achieved compared to the basic model based on increased capital and operating inputs (e.g. more manpower, more Pollution management expenditures in Bangladesh currently fall significantly below what is deemed necessary (for example, see the recent "Rally for Rivers" campaign headed by Bangladeshi media activists that highlight the lack of manpower, finance/budgetary support and integrated pollution management approaches), suggesting significant opportunity for increased spending and institutional reform/coordination to handle such an approach. Rethinking pollution costs and environmental liability: Given the current situation in pollution control (the "basic" model), it may be suggested that the government needs to rethink the relationship between pollution and costs, together with a decentralised sourcing of financing and cost recovery with the participation of local government and private companies. New sources of financing will be helpful in reforming the stakeholder agencies, and also for the planning and implementation of new pollution management initiatives (pollution management here includes control and abatement, taken together to mean the use of control strategies for pollution "clean-up" and the promotion and use of cleaner production technologies that prevent pollution from happening). International best practice thinking on "full cost recovery accounting" of pollution management, "user pays principle" and "polluter pays principle" can have significant benefits for a new phase of financing Bangladeshi environmental regulation. A full cost recovery study is needed to link the pollution management costs to polluter and the amount of wastes/pollution generated (plus projected growth due to increased industrialisation). This study is crucial to designing enhanced models (basic to intermediate or integrated) that are financially self sustaining; revenue generating for the DoE and other GoB agencies; protective of human health and ecology; and minimises pollution to be generated and treated. This study will need to determine the public's "willingness to pay" for pollution that they generate; and will need to segregate between identifiable polluters (e.g. tannery owners) and general polluters (e.g. householders). The government's pollution management model (improving it from basic to intermediate or integrated) and the full accounting study should obviously be linked via the model's objectives and mechanisms for achieving those objectives. The full accounting requirements, opportunities for interventions and benefits (magnitudes and types) will vary depending on the policy model adopted (basic to intermediate or integrated). Regardless of the policy model chosen, the cost recovery of pollution management will depend on the pollution characteristics, management options (e.g. CETPs or ETPs, etc.) and how the polluters will pay for it. The full cost recovery study should assign a cost to all negative impacts of pollution and include a cost recovery schedule/plan consistent with identified costs. It should include normal operating plus annual costs (e.g. administration, training, enforcement, public education/awareness, performance monitoring and capital replacement). This will provide a sense of how to design cost recovery mechanisms (taxes, incentives, contracts, etc.) Generally, the full cost recovery study should deliver a full cost recovery strategy. As mentioned above, the cost recovery study should calculate environmental costs of pollution, and do a willingness to pay analysis. The subsequent cost recovery strategy will then determine the funding opportunities the government should use the following for funding a new pollution management model/strategy: 1. The existing "baseline public sector subvention" from revenues (e.g. environmental clearance certificates from the industries, water utility bills from the public, etc.); 2. New revenue generated via the "polluter pays principle" on manufacturers, importers and distributors that can be reasonably identified as being responsible for pollution (special earmarked "green" taxes/penalties/ subsidies for polluting industries depending on their pollutant loads, quantities and willingness to ecologise); and 3. New revenue generated via the "user pays principle" for other tasks (e.g. surcharges in household water bills etc. to pay for the construction and O&M of the effluent treatment facilities that deal with the pollution load). The full cost recovery strategy should include local government as important stakeholders and agents in collecting and generating new pollution revenues. Financing can come from public or private sector entities, and from internal and external sources. Traditional sources of revenues (DoE's environmental clearance certification system, for example) will continue to play an important role as an internal source of finance. Policymakers may consider innovative options of concession contracts, which usually mean that a private company enters into an agreement with the government to invest in, operate and maintain a public utility (e.g. waste management centre) for a set number of years. Alternatives include a lease contract (e.g. a private company operates and manages the waste treatment facility, but the government builds it using taxes) and a management contract (e.g. the government builds the waste management centre, but the private company will only collect revenues from the regulated and in exchange be paid a fee). Policymakers also may consider an innovative institutional set up or reform for implementing the new PPP driven environmental management model. This may include either creating a core group of agencies who will receive funds and carry out environmental pollution management functions as befits their original mandate or, policymakers may consider a simpler arrangement whereby a pollution control board is set up that will oversee the implementation of PPP. Public understanding and acceptability will be critical for the success of such enhanced pollution management and cost recovery implementation (on the basis of "polluter pay" and "user pay" principles). Once the cost recovery study is done, a phased introduction scheme is to be devised at the local level (involving pouroshobhas) accompanied by an explanation of enhanced pollution management services to the public. This should be followed by an effective public awareness and communication initiative (possibly building on the burgeoning media activism in Bangladesh that has been much lauded by the government and the public) on the new role of the Bangladeshi citizen as an industrial polluter or a commercial enterprise owner or a householder. Environmental quality is our birthright and adopting a PPP approach is challenging but critical first step towards ensuring that birthright for ourselves and our future generation. Photos: AFP Source: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ BANGLADESHEXTN/Resources/295759-1173922647418/complete.pdf Dr. Shahpar Selim has a Doctorate in Environmental Policy from the London School of Economics and Political Sciences, UK. |

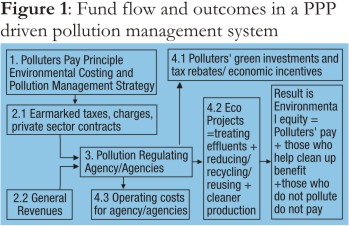

capital costs etc. funded through new green taxes and GOB budgetary allocations). While this provides for environmentally sound management of pollution, it does not necessarily target pollution at the source ("cleaner production" or recycle-reuse-reduce options) and continues to rely on "cleaner disposal" over "simple removal" under the basic model. A more stringent model might be the "integrated" model an approach that slows the rate and amount of pollution generation and encourages recycle-reuse-reduce options. This approach will distribute the "burden" of pollution costs across society in more equitable ways than the current basic model. While the initial financing and recurrent costs of this model is higher than the basic or the intermediate models, the longer term costs may be lower. See figure 1 for the model at a glance.

capital costs etc. funded through new green taxes and GOB budgetary allocations). While this provides for environmentally sound management of pollution, it does not necessarily target pollution at the source ("cleaner production" or recycle-reuse-reduce options) and continues to rely on "cleaner disposal" over "simple removal" under the basic model. A more stringent model might be the "integrated" model an approach that slows the rate and amount of pollution generation and encourages recycle-reuse-reduce options. This approach will distribute the "burden" of pollution costs across society in more equitable ways than the current basic model. While the initial financing and recurrent costs of this model is higher than the basic or the intermediate models, the longer term costs may be lower. See figure 1 for the model at a glance.