Inside

|

The Curious Case of the 195 War Criminals Syeed Ahamed looks back at how justice eluded our grasp

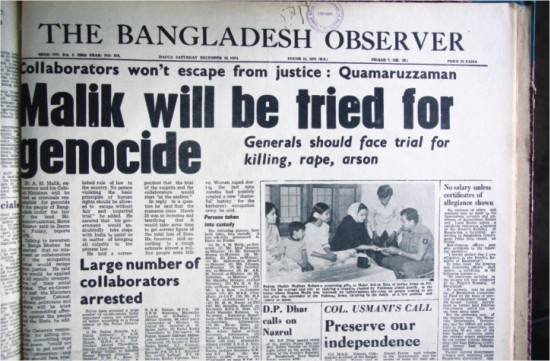

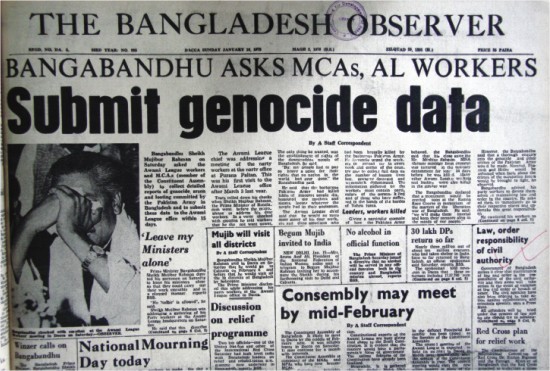

As soon as the trial of war criminals began, questions were raised from different quarters as to how and why the 195 Pakistani soldiers were released in 1974 without any trial. It has also been argued that those 195 Pakistanis were the main war criminals and their release questions the merit of the current trial process.1 This article investigates the news reports that were published in international media from December 16, 1971 to April 15, 1974 to understand how and why those 195 Pakistanis were accused and released. It also explores the avenues the post-1971 Bangladesh government pursued to put Pakistani and local war criminals on trial. To remain true to the fact, the article mostly cites news reports and avoids opinion pieces. Also, to remain consistent, the article mainly cites the New York Times, though similar news was published in other newspapers. Relocation of POWs to India Hence, in the second week of December, Lt. Gen. A.A.K. Niazi sent a request to the Indian high command for ceasefire. On December 15, 1971 Gen. Sam Manekshaw, Indian chief of staff, rejected Niazi's call and asked him to surrender by the next day. He however assured that safety of Pakistan's military and para-military forces would be guaranteed.4 When the Pakistani force made the rare public surrender to the Joint Command of India and Bangladesh on December 16, 1971, the "Instrument of Surrender" particularly highlighted this issue: Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Aurora gives a solemn assurance that personnel who surrender will be treated with dignity and respect that soldiers are entitled to in accordance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention and guarantees the safety and well-being of all Pakistan military and para-military forces who surrender.5 Hence, when sporadic post-war clashes erupted in different parts of Bangladesh, India became concerned about the safety of the 90,000 POWs. Indian Maj. Gen. Dalbir Singh, who accepted the surrender of some 8,000 Pakistanis in Khulna, mentioned that their main concern at that time was to move the POWs to Indian camps and withdrawal of Indian troops. He also added that, since the collaborators were not covered by the Geneva Convention on POWs, "they will be the responsibility of the Bangladesh government."6 Trial of War Criminals On December 26, widows of seven Bangladeshi officers killed by the Pakistanis asked India to help Bangladesh try the Pakistani soldiers for their crimes. In response, Indian envoy Durga Prasad Dhar, with an apparent reluctance, said: "India is examining its responsibilities [towards the POWs] under international law."7 The leader of the liberation movement Sheikh Mujibur Rahman -- soon after his return from captivity -- initiated a formal process of war crimes trial. On March 29, 1972, Bangladesh government announced a formal plan to try some 1,100 Pakistani military prisoners -- including A.A.K. Niazi and Rao Forman Ali Khan -- for war crimes.8 The government offered a two-tier trial process -- national and international jurists for some major war criminals (probably for the high command of Pakistan army); and all-Bangladeshi court for the rest of the war criminals.9 Initially, India agreed to hand over all military prisoners against whom Bangladesh presented "prima facie cases" (essentially, presenting evidence) of atrocities.10 On June 14, 1972, India agreed to initially deliver 150 POWs, including Niazi against whom Bangladesh gathered evidence of atrocities, to Bangladesh for the trial.11 On June 19, 1972 -- ten days before the meeting between Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Indira Gandhi -- Sheikh Mujibur Rahman reaffirmed his commitment to try the Pakistanis. It is important to note here that, contrary to popular belief, the India-Pakistan Simla Agreement signed on July 2, 1972 had nothing to do with the Pakistani POWs that Bangladesh wanted to prosecute.12 Pakistan Takes Bangladeshis Hostage The International Rescue Committee (IRC) also reported that many Bangladeshis were arrested in Pakistan just for their "alleged intent to leave Pakistan," and thousands were jailed without any charge. It also reported that the civilian Bangladeshis in Pakistan were facing serious discrimination and harassment and were being treated as "niggers."14 Facing widespread torture, hundreds of Bangladeshis began to escape Pakistan through the inaccessible "lawless tribal territory of Afghanistan."15 However, Pakistan government even placed a bounty of 1,000 rupees on each Bangladeshi seized while trying to leave Pakistan.16 The China Card Bhutto knew how critical it was for the war-torn Bangladesh to get the membership of United Nations and he used his friendship with China over this. When Bangladesh applied to the United Nations, China cast its veto on August 25, 1972 for the first time in the Security Council to bar Bangladesh's membership.19 Bangladesh was refused United Nations membership for wanting to try the war criminals. The Trial-Repatriation Deadlock On April 17, 1973, after four days of bilateral talks Bangladesh and India announced a "simultaneous repatriation" initiative to end the prisoner-deadlock. Under this proposal, India would repatriate most of the 90,000 Pakistani POWs. In return, Pakistan would release the 175,000-200,000 stranded Bangladeshis and take back 260,000 non-Bangalis (Biharis) from Bangladesh.21 Bangladesh, however, made it clear that India would not release 195 of the initially accused Pakistani POWs and Bangladesh would try them, along with its local collaborators, for war crimes. Pakistan accepted the proposal in principle, but agreed to take back only 50,000 Biharis. Bhutto however furiously refused Bangladesh's position to try the accused Pakistanis in Bangladesh. He threatened that if Bangladesh carried out the trial of the 195 Pakistanis, Pakistan would also hold similar tribunals against the Bangladeshis trapped in Pakistan. In an interview on May 27, 1973, Bhutto said: "Public opinion will demand trials [of Bangladeshis] here … We know that Bangalis passed on information during the war. There will be specific charges. How many will be tried, I cannot say."22 To prove that it was not just an empty threat, Pakistan government quickly seized 203 Bengalis as "virtual hostages" for the 195 soldiers.23 Bhutto also argued that, if Bangladesh tried its POWs, Pakistanis who were already "terribly upset" would topple Pakistan's political leadership, and he claimed that his government had already arrested some top-ranking military officials for such conspiracy.24 Meanwhile, on August 28, 1973, India and Pakistan signed the Delhi Accord, which followed the Bangladesh-India "simultaneous repatriation" proposal. This allowed the release of most of the stranded Bangalis and Pakistanis held in Pakistan and India respectively for almost two years. The tripartite repatriation began on September 18, 1973 and some 1,468 Bangalis and 1,308 Pakistanis were repatriated within the first week.26 Pakistan and India agreed that the issue of 195 accused Pakistanis would be settled between Bangladesh and Pakistan.27 Pakistan kept the 203 Bangladeshis out of this repatriation process.

Legal Preparations On July 15, 1973 Bangladesh amended its constitution for the first time to ease the process of the war crimes trials. Article 47 (3) of our national constitution, added under the first amendment, states that: 47 (3) [N]o law nor any provision thereof providing for detention, prosecution or punishment of any person, who is a member of any armed or defence or auxiliary forces or who is a prisoner of war, for genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes and other crimes under international law shall be deemed void or unlawful."28 On July 20, 1973, the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 was announced "to provide for the detention, prosecution and punishment of persons for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and other crimes under international law."29 Interestingly, though the trials of the collaborators were abandoned, Article 47(3) and the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973 -- which offers the trial of war criminals including the "auxiliary" forces for their crimes against humanity -- were not cancelled by any government and are still applicable. Simultaneous trial and Pakistan's apology Pakistani government rejects the right of the authorities in Dacca to try any among the prisoners of war on criminal charges, because the alleged criminal acts were committed in a part of Pakistan by citizens of Pakistan. But Pakistan expresses its readiness to constitute a judicial tribunal of such character and composition as will inspire international confidence to try the persons charged with offenses.30 After about one year, Bangladesh finally accepted Pakistan's proposal, fearing for the fate of 400,000 Bangalis trapped in Pakistan and to gain the much-needed access to the United Nations. With faith that Pakistan would hold the trial of the 195 Pakistanis involved in the wartime atrocities, Bangladesh withdrew its demand for trying the Pakistanis in Dhaka. Upon the formal understanding, the last group of 206 detained Bangladeshis was allowed to return home on March 24, 1974.31 It is clear that the 195 Pakistanis were not freed without charges, rather they were handed over to Pakistan so they could be prosecuted by the Pakistani authorities. Bangladesh's position was then formalised on April 10, 1974 through a tripartite agreement among Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. It was reported internationally that Pakistan government offered apology to Bangladesh on the same day.32 Article 14 of the tripartite agreement noted that the prime minister of Pakistan would visit Bangladesh in response to the invitation of the prime minister of Bangladesh and "appealed to the people of Bangladesh to forgive and forget the mistakes of the past in order to promote reconciliation." At that time, Bangladesh continued the trial of local collaborators and hoped that Pakistan would keep its promise and try those soldiers for the horrific crimes they committed against humanity. 1 Pro-BNP, Jamaat lawyers threaten to resist trial of war criminals, The Daily Star, April 17, 2010 2 For details on genocide and atrocities committed by the anti-liberation forces, see www.genocidebangladesh.org 3 Yohn, T. (2001) Letters to the Editor: Who Cares About the Bengali People? The New York Times, Dec 31, 1971; pg. 18 4 Text of Indian Message, The New York Times, Dec 16, 1971; pg. 16

5 Reuters, (1971), “The Surrender Document” published in the New York Times, Dec 17, 1971, pg. 1 Sayeed Ahamed is an Australia-based public policy analyst and is a member of Drishtipat Writers Collective. |