Inside

|

Bollywood and Dhallywood:

Contentions and Connections

ZAKIR HOSSAIN RAJU analyses the perceived threat of Bollywood to the Bangladeshi film industry.

Photo: PRITO REZA

Photo: PRITO REZA

Dateline Dhaka, 1 July 2011. The leading Bengali daily Prothom Alo reports: 'Indian film enters the country [Bangladesh]' (Entertainment Reporter 2011: 20). The report elaborates that three Indian-Bengali films were released from the airport upon a court order and are now awaiting the clearance of Bangladesh film censor board for being shown in local theatres. Within two weeks, it reports again with a heading: 'the Film Fraternity fights back the Indian films [in Bangladesh]' (Kamruzzaman 2011: 20). It outlines how the five different associations of film professionals working at Dhaka Film Industry promise to oppose 'the exhibition of Indian films till the last' and urged the government to intervene. On the other hand, the film exhibitors' association wishes to bring more Indian films as '[local] film production is dwindling, the audiences are not watching these films like before and the producers are also losing money'. (Kamruzzaman 2011: 20).

It seems that our local film industry, Dhallywood, is in a David-versus-Goliath situation and only the state can save the industry in this uneven war. How much is it true? Are we really out of bound of Bollywood, or is this only another myth? Keeping Indian films outside cinema halls (while these are already inside our living quarters) are not we behaving like children? I contend that there are complex connections and contentions that relate as well as detaches the cinemas of India and Bangladesh (in the rest, I would use Bollywood and Dhallywood to mean these two cinemas) -- this article is an attempt to construct a framework to look at such a relationship.

Today, we use the shorthand Bollywood at such a rate and in a way as if it was always there. Before we go further, let us ask what needs to be asked: what is Bollywood? Following Ashish Rajadhyaksha, a leading Indian film scholar, I also take Bollywood to be an ensemble of Indian, Hindi-language visual cultural discourses that includes media materials ranging from film, television, advertising to fashion, music and websites connected to Hindi cinema (2004: 114).

Today, we use the shorthand Bollywood at such a rate and in a way as if it was always there. Before we go further, let us ask what needs to be asked: what is Bollywood? Following Ashish Rajadhyaksha, a leading Indian film scholar, I also take Bollywood to be an ensemble of Indian, Hindi-language visual cultural discourses that includes media materials ranging from film, television, advertising to fashion, music and websites connected to Hindi cinema (2004: 114).

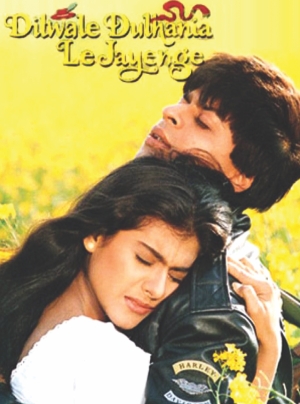

And since when has the term Bollywood gained currency? Actually, the revival of the term has a short history. Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ) made in 1995 is arguably the first Hindi film that normalised the usage of the term Bollywood. Leading Indian film scholar Ravi Vasudevan traces the trajectory of the term:

I only started noticing its regular usage in the latter part of the decade [1990s]. Clearly, it may have been used various times, but not so systematically as now. …[I]t emerged in the wake of the success of the diaspora-themed films from DDLJ onwards. More specifically, the term might then be associated with the reinvention of the family-film genre to address not only diaspora audiences but to provide a mise-en-scene for the new types of commoditization that have developed around cinema in India. (2010: 339-40)

Then how is one to define 'Bollywood' in Bangladeshi context, especially in relation to Dhallywood? Especially when Bollywood films are extensively seen by the local audiences with no direct diaspora experience, what usage of Bollywood do they vie for? In other words, for the audiences who have their national roots in Bangladesh -- how do they perceive Bollywood? In that way, the key question I pose in this essay -- how does Bollywood relate to Bangladesh's own film industry, especially when the protective nation-state wishes to guard its culture with a serious suspicion of anything 'Indian'? I answer these questions by delving into the history and current state of Dhaka film industry in relation to importing and appropriating Bollywood in its own arena. When doing this I do not take Bollywood only as a post-1995 entity, I rather place it in a 50-year historical map. I go through some flashbacks to identify some key moments when Bollywood was seen as a major threat both for Bangladesh and its own film industry -- that is Dhallywood. Interestingly, these moments, are some 'nationalist moments' (drawing on Partha Chatterjee here) -- moments when Bollywoodisation was considered as 'Indianisation' and as such it had to be opposed by Bangladesh state through various measures.

Bollywood and Dhallywood: Connections and contentions through five decades

The nation-state in postcolonial Bangladesh played an important role in establishing the 'rules of the game', both in terms of constructing a national cinema and a national public sphere. However, the relationships between the state, national public sphere and local cinema culture followed quite a complex trajectory and did not necessarily fulfill the nation-building visions of the pro-West, modernist middle class. Such a nationalist framework of Bangladesh screen media industry was first defined by the state ban on releasing Indian, Hindi-language popular films in theatres in Bangladesh, a ban first imposed during 1965 India-Pakistan war (when Bangladesh was the eastern part of Pakistan). Even in the globalising mediascape of 2010s Bangladesh, both the state and the Bengali-Muslim capitalists kept the local popular film industry within such a protected theatrical-exhibition environment. For around five decades, such state-level commitment of keeping a well-protected 'national' market only for Bengali-language, local popular films helped the Bangladesh film industry to keep the transnational cinemas (notably Bollywood) at bay and expand as a 'national cinema' exponentially. The moments I identify in the historical narrative of this period exemplify such a tug-of-war for Dhallywood and against Bollywood in Bangladesh.

1972: The first nationalist moment (the moment of continuity)

After Bangladesh became an independent nation through a nine-month liberation war in 1971, a fever of renewal was visible in many spheres of national culture and politics here. Against this backdrop, the film producers in 1972 were fearfully waiting to hear that Indian films will no more be out of bounds for local theatres. On the other hand, leading distributors and exhibitors of Bangladesh cinema were gleefully expecting that the newly-established pro-Indian government would again approve the exhibition of Indian popular films in Bangladesh as had happened in pre-1965 East Pakistan. However, surprising everybody, the Pakistani ban against Indian films was kept in action using similar nationalist rhetoric by the Bengali-nationalist government led by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib. When he was approached on the exhibition of Indian films in 1972, Bangabandhu declined such a proposition just saying that 'tell them, those [Indian] films will not be shown in Bangladesh' (Rahman 1990: 8).

Why did the new government in Bangladesh continue the ban against Bollywood? The first and foremost reason was its urge to develop a home-grown modernity that got momentum from the early 1970s not only in the political but also in the economic and cultural spheres. With the emergence of a small group of local capitalists (thanks in part to the support and connections of the ruling clique), investments increased in culture-related industries. The film industry received a particularly strong boost of new capital as it was seen as a good sector to invest in and multiply 'black' (that is, untaxed and undeclared) money. This process was fostered through the 1972 decision to continue the ban on the theatrical screening of Indian films, which rendered Dhallywood as the chief provider of visual entertainment to a captive, 'Bangladeshi' (primarily Bengali Muslim) audience. Such a national market for indigenous Bengali-language cinema alongside state-level efforts to construct a 'Bangladeshi' identity amid globalising forces and transnational culture industries (such as Bollywood) propelled the Bangladeshi film industry into becoming a medium-sized popular film industry.

However, in a real sense, Bangladesh film industry was not able to keep Bollywood out of its turf despite the ban in the independent Bangladesh. In the words of film researcher Ahmed:

[T]he flicker of Hindi films remained intact in the minds of the urban, middle to upper class cinema goers: gossip columns in magazines, radio shows, people going to Calcutta and bringing vinyl records back and of course, word of mouth kept the buzz going. As a witness, a 50 year old viewer says, "the word cinema meant Hindi cinema mainly and then Hollywood. Yes, there was Pakistani cinema and of course, Bangladeshi ones, but those were few in number." The 1970s were the decade of Amitabh Bachchan, the biggest Bollywood star till date and the Bangladeshi fan base missed out on that in cinema theatres. But they were always aware of all the gossip through media. The fascination toward Bollywood was there even without the content itself. (Ahmed, 2010).

So even when Bollywood films were made out of bounds for local audiences, still two modes of appropriating Bollywood signified its power over 1970s Bangladesh: public memory and the print media. There was also a third mode, more concretely working than the first two -- plagiarising Bollywood films for Dhallywood film industry.

Plagiarism in the form of copying Hindi popular films started within a few years. A trip to Calcutta or a nearby Indian city enabled local film directors/producers to get a glimpse of a Hindi blockbuster film and then they copied that to prepare a Bangladeshi version, sometimes scene by scene. It was the case for Dost-Dushman (Friend and Enemy), a Bangladeshi remake of legendary Indian 'Curry Western' film Sholay (Flames, 1975). This 1977 film copied Sholay very truthfully though the film crew did not acknowledge that in the titles of the film. Following Sholay, it became the first Bangladeshi film to portray a number of lengthy action scenes (and hence has been condemned by many film critics for bringing violence to the cinema screen in Bangladesh). While the modern middle classes regarded the action genre as being contrary to their cultural-national ideals, the film also heralded the beginning of the inevitable interaction between Bangladeshi 'national' cinema and Hindi action films. Interestingly, such Bollywoodisation took place in South Asia in the 1970s when the transnational movement of films and media were much restricted. In other words, a look at Dost-Dushman takes us to the Indianisation of Bangladesh mediascape in the 'yesteryears', that is, in the 1970s, a period that is normally considered as 'pre- or early-globalisation' phase and then normally put out of purview of the scholars of cultural globalisation. Dost-Dushman thus can be taken as an early instance of cultural migration between Bollywood and Dhallywood.

|

Photo: PRITO REZA |

1983: The second nationalist moment (the moment of arrival)

Though the Bollywood-copied films such as Dost-Dushman expanded the film viewership in the late 1970s Bangladesh especially bringing in semi-urban, working-class audiences to theatres, ironically these 'plagiarised' films contested the cultural-modernist vision of nation-building, a vision that was mainly projected by the western-educated middle class intelligentsia. From the late 1970s to the late 1980s when the state under General Zia and Ershad encouraged Islamism in various ways in order to strengthen a communalist sense among Bengali Muslims and thus enhance their power, such a process was in conflict with the higher level of penetration of 'un-Islamic' and non-Bangladeshi media materials.

For example, with the availability of consumer VCRs, a trend of consuming Bollywood films at the household level started in the early 1980s. Elsewhere, I have elaborated the situation in the following manner:

Small video-theatres started mushrooming in the cities and towns of Bangladesh offering films like Disco Dancer, Qurbani, Kabhi Kabhi, Silsila, Love Story, Sholay, Shaan, Muqaddar Ka Sikandar and Lawaris for an entry fee of 10 Taka (US 20 cents) only. Nightly rental of VCRs with four or five videos of Hindi films also became very popular. Amitabh Bachchan, Mithun, Zeenat Aman and Hema Malini quickly became familiar names and popular icons among the middle and lower-middle class viewers here amid the 'culture war' between India and Bangladesh. (Raju 2008: 158)

Bangladesh government issued permission for importing video-players in June 1979 while announcing the annual budget for the fiscal year 1979-80. Just after that, the chairperson of Bangladesh film exhibitors' association Iftekharul Alam and the renowned film director Dilip Biswas commented that from then onwards there would be cinemas in every household and eventually the audience in theatres would decrease in a greater number (Weekly Bichitra 1979: 74). With these apprehensions, the state formulated a new package to save the 'Dhakai' cinema from the clutches of Bollywood that started to penetrate Bangladesh market in the form of video since late 1979. From October 1983, the capacity-based tax, as it is called, transformed Bangladesh cinema into a larger industry as well as encouraged it to serve the 'national' public sphere by producing vernacular films in greater numbers for a greater number of audiences.

Similar to the 1972 ban of Indian and Pakistani films in cinemas, the capacity tax system imposed in late 1983 can be seen as an incentive to keep a 'nationalised' film exhibition environment in Bangladesh. This new method of collecting tax from the theatres as per the capacity seemed quite profitable to the theatre-owners and also to the film producers-distributors. Under the capacity-based tax system, the cinemas pay the tax as weekly installments in advance while the amount to be paid is determined by the revenue department through assessment of the capacity of a particular cinema. By assessing the 'importance' of the location of a theatre, the revenue department asks the theatre to pay between 5% (for a rural theatre) to 50% (for a theatre in the major cities) of the amount they would earn if the theatre was full in all the screenings of a week. As the new tax amount (100% of the entry fee multiplied by 5-50% of the capacity) is much lower and easier to manipulate than the previous 'pay-per-viewer' taxation system, the cinemas in 1980s Bangladesh could earn much more than before. Film historian Quader noted that because of such corruptive measures, the revenue income of the government from the film exhibition sector decreased by 25% during the mid-1980s. Because of the large amount of unpaid taxes, the government had to lodge certificate cases against some 200 theatres in June 1988, as a result of which some theatres had to close down. (Quader 1993: 415)

Similar to the 1972 ban of Indian and Pakistani films in cinemas, the capacity tax system imposed in late 1983 can be seen as an incentive to keep a 'nationalised' film exhibition environment in Bangladesh. This new method of collecting tax from the theatres as per the capacity seemed quite profitable to the theatre-owners and also to the film producers-distributors. Under the capacity-based tax system, the cinemas pay the tax as weekly installments in advance while the amount to be paid is determined by the revenue department through assessment of the capacity of a particular cinema. By assessing the 'importance' of the location of a theatre, the revenue department asks the theatre to pay between 5% (for a rural theatre) to 50% (for a theatre in the major cities) of the amount they would earn if the theatre was full in all the screenings of a week. As the new tax amount (100% of the entry fee multiplied by 5-50% of the capacity) is much lower and easier to manipulate than the previous 'pay-per-viewer' taxation system, the cinemas in 1980s Bangladesh could earn much more than before. Film historian Quader noted that because of such corruptive measures, the revenue income of the government from the film exhibition sector decreased by 25% during the mid-1980s. Because of the large amount of unpaid taxes, the government had to lodge certificate cases against some 200 theatres in June 1988, as a result of which some theatres had to close down. (Quader 1993: 415)

Such nationalist remedy through tax reform in film exhibition brought major capital investments in the industry. However, with much higher capital requirements, it became critical to reach a mass audience by cheapening the film content. Plagiarism, that is copying entire films or at least parts of the film from a popular Hindi film, became a normal practice in such a degradation of Dhaka films. Through such an overt 'Bollywoodisation' process, Dhakai cinema in the 1980s became a vibrant, vernacular-language national film industry. However, such a process sharply divided the viewership of screen media in Bangladesh in two groups. The first group consisted of those who patronised vernacular, Bollywood-copied films on big screen in the local cinemas. The other group comprised those who preferred original, Hindi-language, Bollywood films which they collected on videotapes and enjoyed on small screen.

Film researcher Ahmed comments:

After 15 years of exile from Hindi cinema, the fans finally got to watch the films instead of listening to records of Sholay (1975) over and over. Of course it did not matter whether it was pirated or not. A point to make is that, this phenomenon was primarily true for Dhaka city only during the early 80's. But when low cost Chinese made VCP (Video Cassette Players) came around, VHS rental stores spread all over the country. They were now accessible in the small towns, in the major market place near a cluster of villages. (Ahmed 2010: 3)

Such circulation of Bollywood films on videotape in urban and semi-urban Bangladesh encouraged the film producers to copy these, make a local version and hope for sure success in the box office. In 1980s-90s Bangladesh, this process was also fostered by film exhibitors. It needs to be noted that due to the 'nationalised' exhibition environment secured by the state-ban on theatrical-exhibition of Bollywood films, a significantly high rate of profitability lies in the exhibition of Bangladesh popular cinema. After the state, film exhibitors or cinema-owners, in collaboration with the intermediaries, engaged in film distribution business earn more money from the box office than film producers.

Other than the state, thus film exhibitors have also become important financiers in popular film production, in most cases investing their 'black money'. Because of such exhibitor-based financing of a film, if a Dhallywood film producer can somehow put together around 40% of the total budget of the film, he proceeds to produce a film with the hope that he can collect the rest pre-selling the film to the exhibitors after some shooting has been completed. However, such pro-state and pro-exhibitor financing of popular films converted Dhallywood into a vulnerable film production industry in 1980s-90s Bangladesh, which largely depended, ironically, on Bollywood -- its arch rival -- especially for developing on-screen storyline and attractions such as songs, dance and fight scenes.

The fragile arrangement of multi-source financing of film production in Dhallywood necessitates that the film has to be completed and released very quickly as the investors want their return at the earliest. The cast and crew including the director of the film is then always under pressure from the financiers to complete the film and naturally all of them work in a stopgap manner. This kind of pressure developed an easy and consensual procedure of film production in Bangladesh in the 1980s-90s -- copying the storyline and other elements from a Bollywood film. So eventually, the state and local film exhibitors, the Bengali Muslim 'nationalist' forces, actually de-nationalised Dhaka film industry bringing in film plots, screen/visual imageries or even some 'foreign' genres from Bollywood.

1997: The third nationalist moment (the moment of circulation)

At the end of the 1990s, it became clear that only plagiarising Bollywood films for the local audiences in theatres was no longer working! The film exhibitors in Bangladesh again felt the same fear that they felt with the arrival of Bollywood in the videotaped format 15 years earlier. This time the new genie was Satellite Television -- they now needed to cope with the invasion of the 'video channels' (that means, the cable-connected local network put up by the suburban private satellite television service providers). Dhaka Film Exhibitors' Group complained in October 1997 that film exhibition business all over the country including Dhaka city is under serious threat of 'video channels': the newly-released Bollywood films are now being shown through the 'video channels' -- the audience can watch these films sitting in their homes paying next to nothing while the number of audience in theatres has gone down. They argued that while the middle class audience have stopped going to cinemas [since the early-1980s] as they can watch all the 'Indian higher standard films and television programmes' through a number of satellite channels, only a section of the lower income people have allowed Dhallywood to survive till now. But now as they can also watch all the new features through the 'video channels', soon film producers will be on the streets and film exhibitors would have to close down the theatres as they can afford no more losses. (Daily Ittefaq 1997: 20)

Alongside the video channels, digital copy media, that is VCDs and DVDs, also became very common in the cities and small towns in the late 1990s-early 2000s Bangladesh. The production and distribution of the pirated DVDs of Bollywood films has taken a more professional turn since then. The new Bollywood films are available as pirated DVDs during the same week (if not before) the film was released in cinemas in India or elsewhere. Each month, more than seven million VCDs and DVDs are imported and/or produced in Bangladesh most of which carry Bollywood films (Hasan 2008: 16). Interestingly, pirated VCDs/DVDs of Bollywood films became so omnipresent in the 2000s Bangladesh that the people here who are selling, copying, buying, renting, borrowing and viewing these never view their act as some kind of illegal transaction!

So, during the last 15 years or so, Bollywood films in Bangladesh are circulated through at least three powerful vehicles: numerous Hindi-language channels on satellite television, Bollywood films on so-called video channels attached to cable television and the large-scale availability of pirated DVD-borne Bollywood films. Though Bollywood is still absent in cinema theatres, its circulation has reached almost the entire population in Bangladesh. In a way, the earlier division between the ones watching Bollywood on videotape and the others watching films-plagiarised-from-Bollywood on cinema screens are no more valid.

Such transformation in the viewership of screen media also led to generic transformations in Dhallywood cinema. Firstly, the 'social' films (read family-drama films) depicting traumatised, sentimental heroes and soft, vulnerable and victimised heroines signifying the well-accepted gender roles in Bangladesh society have almost disappeared from film screens. Action cinema as a major genre developed in the 1980s-90s, especially to meet the challenges brought forward by the influence of Bollywood. While social action films became the staple of Bangladesh cinema since the late-1980s, within a decade this turned to be an extreme-action genre. Vivid scenes of dismembering certain body parts of the opponents started to be presented on screen as part of these extreme-action films.

As we experienced, during the middle of the 2000s (especially in the years 2002-07), Dhaka film industry produced almost nothing but extreme-action films. Most of these action films incorporated short, uncensored clips of nude or sexually explicit scenes (locally termed as 'cutpieces') especially to be shown in cinemas in semi-urban areas outside the big cities. The middle class intelligentsia call these films 'vulgar' (in Bengali: 'Oshlil'). Such a wave of 'vulgar' films can be read as an effect of globalisation and Bollywoodisation that trickled to the rural audiences unable to access sexually provocative materials in digital formats. In late 2007, a decisive police action against the film industry initiated by the then army-backed caretaker government, claimed to clean up all the 'vulgar' films and their producers. During 2008-10, there was a renewed wave of social films and a very limited number of action films that can be located in the Dhaka film industry. No cutpiece-incorporated films are being made, though the 'vulgar' films made earlier are slowly getting back into circulation. The police action has, however, stopped the high energy of Dhallywood industry for the moment. In the first six months of 2011, Dhallywood produced only 19 films. So, the number of annual films has halved and cinema attendance is also dwindling. Many cinemas in the big cities are on the verge of transforming into shopping malls or condominiums!

Photo: PRITO REZA

Photo: PRITO REZA

The Future: Bollywood on big screen?

During 2010-11, a new drama scene is unfolding for Dhallywood. In its battle against Bollywood, it is going through a turbulent time. During early 2010, the film exhibitors showed strong interest in importing and screening Indian popular films in a bid to preserve the exhibition sector. The state seems to be less nationalist than before and in a double bind on the issue. In the first instance, it approved the import for the time being and then stopped it amid the protests from film directors and producers, who claimed that the practice would put a death nail into the local film industry as well as destroy national culture with the complete invasion of Bollywood. However, the status quo seems to be short-lived as in June 2011, because of a court order the government provided NOC (No Objection Certificate) to censor three Indian-Bengali films that I mentioned in the beginning.

Photo: PRITO REZA

Photo: PRITO REZA

Om Shanti Om, Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna, My Name is Khan, Three Idiots, Dabaang and Main Hoon Na are among the Bollywood films that are now awaiting such approvals from the government (Entertainment Reporter 2011: 20). Will these films be screened in our local cinemas soon? Will Dhallywood be rid of the long-lasting protection it has been bestowed by the state for almost five decades now? We have to wait and see how the state tackles such a tricky situation in the next few months. Whether or not that happens (for now!), Dhallywood -- in order to fight the forces of globalisation, most visible as transnational screen media like Bollywood -- must revitalise itself to take the full advantage of media convergence in this age of globalisation. The state must realise that the ban on Bollywood cannot ensure the continuity of this 'golden goose' anymore. We need to modernise not only Dhallywood, but we also need a well-developed screen media culture, so that we do not need to worry about Bollywood as a genie anymore!

References

Ahmed, Tazeen (2010) 'Piracy and Bangladesh Film Industry', unpublished MA dissertation, University of Westminster, UK.

Daily Ittefaq (1997) 'Stop Illegal Film Exhibition through Video Channels', 23 October: 20.

Entertainment Reporter (2011) 'Indian film enters the country [Bangladesh]' Daily Prothom Alo, 1 July: 20.

Hasan, M. (2008) 'Influence of Hindi Culture in Bangladesh', Daily Naya Digonto, 13 January: 15-16.

Kabir, Alamgir (1975) 'The Cinema in Bangladesh', Sequence 2 (2) (Spring), p. 17.

Kabir, A. (1979) Film in Bangladesh, Dhaka: Bangla Academy.

Kamruzzaman (2011) 'the Film Fraternity fights back the Indian films [in Bangladesh]' Daily Prothom Alo, 19 July: 20.

Khondokar, Manik (2002) 'We need Operation Clean Heart in Film Industry,' Jai Jai Din 19.12 (31 December): 37.

Quader, M. T. (1993) Bangladesh Film Industry, Dhaka: Bangla Academy.

Rahman, K. (1990) 'Tell Them…in Bangladesh', Weekly Chitrali, 13 April.

Rajadhyaksha, Ashish (2004) 'The Bollywoodization of Indian Cinema: Cultural Nationalism in a Global Arena', in Preben Kaarsholm, Cityflicks, Calcutta: Seagull, 113-39.

Raju, Zakir Hossain (2008) 'Bollywood in Bangladesh: Transcultural Consumption in Globalizing South Asia' in Media Consumption and Everyday Culture in Asia, ed. Youna Kim, New York: Routledge, pp. 155-166.

Vasudevan, Ravi (2010) The Melodramatic Public: Film Form and Spectatorship in Indian Cinema. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

Weekly Bichitra (1979) 'Filmmakers Afraid for VCR and TV' 8(7) (29 June): 74.

Zakir Hossain Raju is Associate Professor at Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB). He obtained PhD in Cinema Studies from La Trobe University, Melbourne in 2004. His forthcoming books include Bangladesh Cinema and National Identity: In Search of the Modern? (Routledge: London), Culture, Media and Identities (Open University: Malaysia) and Film in Bangladesh: A Defiant Survivor (Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema: New Delhi and Colombo).