Inside

|

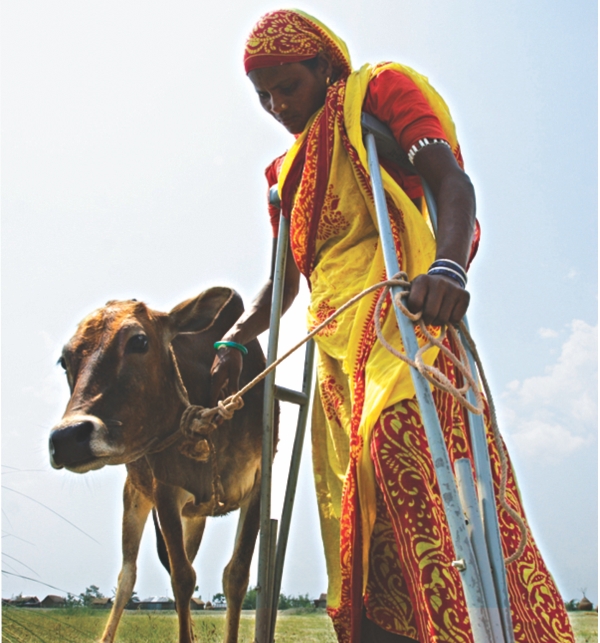

PHOTO COURSTESY HANDICAP INTERNATIONAL

PHOTO COURSTESY HANDICAP INTERNATIONAL

Disability Rights and the Road to Legal Reform

Efforts to introduce new legislation on disability fall short of Bangladesh's obligations under international law, argues HEZZY SMITH.

The Government of Bangladesh ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and its Optional Protocol on November 30, 2007. Internationally, the CRPD has enjoyed immense support: it was drafted and entered into force more rapidly than any other UN human rights treaty. In many countries, ratification of the CRPD has augmented the advocacy efforts of persons with disabilities and their representative organisations.

The CRPD legally binds States Parties like Bangladesh to fulfill its obligations. One of the most important obligations in the CRPD is legal reform. In particular, States Parties must eliminate discriminatory laws and also enact effective protections against disability-based discrimination. Indeed, international disability law experts have noted that full implementation of the CRPD without enabling legislation will likely be impossible.

Supported by dedicated disability rights activists, the Government of Bangladesh has been working towards enacting a new disability rights law for several years. However, successive legislative proposals have not approached fulfilling key CRPD obligations. New legislation alone will not satisfy article 4(1)(b) because several existing laws are discriminatory for the purposes of the CRPD. Nor will ineffective protections against discrimination satisfy article 5(2).

To date, legislative proposals have not adequately addressed shortcomings resulting from existing laws. Nor have legislative proposals created effective protections against disability-based discrimination. As such, ongoing efforts are not likely to yield reforms that will satisfy the Government of Bangladesh's obligations under the CRPD.

Existing discriminatory legislative provisions: Employment

The Bangladesh Labour Law, 2006 enacted more comprehensive benefits for workers, including maternity benefits, dispute resolution mechanisms, and minimum safety and hygiene standards. The Labour Law also expanded he universe of beneficiaries to include the staff of hospitals, nursing homes and non-governmental organisations. Another important aspect of the Labour Law strengthens workers' compensation for work-related injuries. Workers who become partially or permanent disabled during the course of their employment are entitled to compensation proportional to the degree of their disablement up to Tk. 150,000 for permanent disablement (about USD 2,000). Workers can sue for payment in one of the seven Labour Tribunals established in each division.

Although the Labour Law increases the compensation available to workers who acquire disabilities and also establishes specific means by which they can claim that payment succinctly provides that, it also affords employers a great deal of discretion in discharging such workers. Under § 22(1), the law provides that “[a]ny worker may be discharged on the basis of physical or mental incapacity or continued ill health as certified by any registered medical practitioner.” Nowhere in the law, however, is this discretion qualified by considerations regarding the worker's ability or desire to continue his employment in spite of an acquired disability. An employer fearful of diminished productivity may lawfully discharge an employee who has acquired a disability even if in reality that employee is capable of fulfilling his or her former offices.

Employers are effectively entitled to discharge disabled employees without being required to consider possible reasonable accommodations, even if such accommodations could be readily provided. As such, employers are formally protected to engage in discriminatory discharge on the basis of disability. By contrast, the CRPD requires that employers consider what modifications or adjustments can be made to change working norms and the built environment. Moreover, the CRPD obligates employers to provide auxiliary aids and services where appropriate and reasonable. Compensation alone often does not suffice: the stark reality is that they have more difficulty finding forms of employment than do non-disabled job-seekers.

On the other hand, India's highest courts have ruled that the right to life required that employees who acquired disabilities through their work be reinstated, provided that positions where they could be easily accommodated were available. In 1995, the Delhi High Court in Chandla v. Haryana ordered that an electrical sub-station attendant who lost use of his right arm be reinstated in another available post on the same pay scale. The Chandla court ruled that the right to life required that “the employer must make every endeavour to adjust [sic] him in a post in which the employee would be suitable to discharge the duties.”

In 1991, the Indian Supreme Court in Bihari v. Rajasthan Road Trans. Corp. instituted a sweeping new standard for accommodating workers who acquire disabilities during the course of employment. When the respondents terminated a group of 40 drivers because they developed poor eyesight over the course of their employment, the Court held that they were entitled to be reinstated despite having received

compensation. In so doing, the Court laid out a new scheme that privileged reinstatement and continued employment beyond mere compensation payments, where employers' duty to reinstate former disabled employees was not fulfilled by monetary compensation.

PHOTO COURSTESY: HANDICAP INTERNATIONAL

PHOTO COURSTESY: HANDICAP INTERNATIONAL

The Persons with Disabilities Act's passage reinforced what was by then settled law that disabled workers shall be entitled to accommodations such that they can return to work, even if they have received compensation payment. Bangladeshi law, on the other hand, does not adequately protect the right to equality and non-discrimination of persons with disabilities in regard to employment. By contrast, Indian law provides several instances where persons with disabilities have been able to fight against discriminatory in regard to hiring and discharge.

Existing discriminatory legislative provisions: Education

In 2002, an estimated 2% of disabled children in developing countries received any schooling. Despite the dearth of reliable data on the number of children with disabilities in government schools, available estimates suggest Bangladesh is no exception. A 2005 USAID estimate counted 1,753,121 students with disabilities between ages 6-11 and students without disabilities in the same age group numbered 18,000,000. According to data collected in the same year, the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME) tallied 45,680 children with disabilities among the total 13,070,000 children attending government-operated schools. In terms of percentages, children with disabilities in government schools comprised 0.3 % of the school-going population and only 2.6 % of all children with disabilities attended government schools.

In 2008, the MoPME reported a marginally increased enrollment rate of children with disabilities: 77,500 out of 16,001,605 enrolled students, representing 0.5% of the total population. In addition to mainstream educational services provided, the Department of Social Services (DSS) provides special and integrated education services for up to 1,130 children with disabilities. Other students depend on non-governmental organisations for their education. Taken together, these data suggest that the vast majority of children with disabilities in Bangladesh do not have equal access to education.

At least part of this lack of access is likely due to the absence of specific legal duties to accommodate children with disabilities. The 1990 Compulsory Primary Education Act (CPEA), which requires the government to provide compulsory primary education to all children, outright excludes children on the basis of disability. Under

3, the government is not responsible for providing primary education to a child should the following conditions are met, among others:

* if the child is unable to be admitted to an institution of learning because of ill-health or any other impediment;

* if a government primary education officer considers a child currently receiving public education services as not benefiting equally from those services;

* if a government primary education officer considers a child not admissible in an institution of learning because of mental incapacity.

Each condition could easily be used to bar a large number of students with disabilities from the primary education system: students who learn more slowly than other students, who do not respond well to the methods of instruction in place, and even those who have a different physical appearance from that of other students. Although it may very well that negative attitudes might have a stronger impact on whether children with disabilities receive schooling, parents or children would likely be unable to claim their right to education through legal avenues even if they were so inclined.

More recent legislative and policy developments move towards including children with disabilities in the public primary education system. In 2007, the then Directorate of Primary Education (now MoPME) issued a circular to all primary schools instructing them to include students with disabilities “who are includable.” The Ministry of Education's 2010 National Education Policy calls for the inclusion in mainstream schools of children with disabilities and for the provision of accessible learning materials on a priority basis. Yet these initiatives have not created a legal right to education for children with disabilities. The Bangladesh Disabled Welfare Act (DWA) does not even establish a legal obligation for children with disabilities. Although the plain language of the act does on its face guarantee children with disabilities a free and appropriate education through age 18, this provision is found in the act's Schedule “Gha” § 2, which are not legally binding.

Indeed the Bangladesh DWA provisions are little more than a smoke screen. The India PDA contains language similar to that found in the DWA, but individuals are able to enforce them. In Nat'l Fed'n of the Blind v. Govt. of NCT of Delhi, the Delhi High Court invalidated the rules of a government school for blind students because they barred students after class 10, thereby conflicting with obligations under the PDA. The court even held the school duty-bound to accommodate children with disabilities residing outside that particular school district:

The statutory provisions and objectives cannot be allowed to be defeated or frustrated by parochial and monetary constraints. It is the bounden duty of every State government to ensure that schools providing education facilities to the children suffering from disability are readily available. If financial allocations have to be made by the Central Government because of the demands of the admission on a particular school from children out of another State within the Indian Union, that must be suitably provided.

Although the DWA may provide some prospective basis for protecting the right to equality and non-discrimination in education, those provisions have yet to be enforced as similar provisions in India's PDA have been in at least one case. Before the DWA might be held to create an enforceable right, however, it will likely be necessary for a court to overrule the CPEA.

Ineffective proposed protections against disability-based discrimination

In April 2010, disability rights activists along with BLAST filed a petition in the High Court challenging the discriminatory BCS and JCS Regulations, adopted in 1982. The regulations require that all candidates pass a medical examination that categorically excludes anyone with a disability as defined under the DWA. As many other aspiring candidates with disabilities, the lead petitioner, Shapan Chowkidar, a blind advocate who received his LLB and LLM from Dhaka University and enrolled in Dhaka Bar Association, was barred from sitting for the JCS examinations expressly because of his disability. Although he did succeed in sitting for the BCS examination, he was provided with an incompetent scribe. Despite an initial order to show cause for not finding the regulations unconstitutional, the case is pending.

Were current legislative proposals in force today, Chowkidar would find little relief. Current proposals criminalise discrimination. Criminal procedures create a number of challenges. First, providing fines or jail time for discriminators may be unconstitutional under the right to equal protection of the law. For example, Ireland's High Court ruled a statute that criminalised disability-based discrimination to be ultra vires to the Constitution because it posed too harsh punishments on discriminators. Second, the standard of proof in criminal procedures is much higher; therefore, Chowkidar would have much more difficulty in proving his discrimination claim. Third, Chowkidar would have to rely on state prosecutors to pursue his case and would also be precluded from out-of-court settlements. Finally, since current proposals indemnify government employees, it is unclear whether Chowkidar would have access to remedy at all.

Workshops conducted in 11 districts by activists with disabilities in 2009 show that grassroots persons with disabilities understand that limitations of criminal prohibitions on discrimination. One participant in Sirajganj observed that whenever an employer discriminatorily dismisses a disabled employee, the employee would not benefit from fining an employer or sending him to jail because he would still be out of a job. In none of the 11 workshops did participants voice a desire to criminalise those found to have discriminated against persons with disabilities. Rather, they preferred substantive remedies, such as the provision of actual jobs, to punitive measures.

PHOTO COURSTESY HANDICAP INTERNATIONAL

PHOTO COURSTESY HANDICAP INTERNATIONAL

Moreover, focus group discussions in five districts conducted by BLAST this past year demonstrate the many barriers to justice faced by persons with disabilities. Participants repeatedly noted that for a many reasons disabled victims are often much weaker than opposing parties. As a result, even where evidence strongly favours a disabled victim, the opposing parties prevail. Moreover, disability rights activists supporting disabled litigants often have to face difficult choices whether to pursue protracted,unpredictable litigation when out-of-court settlements might greatly benefit disabled litigants and their families. Criminal procedures would outright bar disabled litigants from successfully settling cases and from what in many cases are more desirable remedies than punishing discriminators.

Towards effective legal reform

A great opportunity to improve on current proposals remains. This past June, disability rights activists in India produced and submitted a bill before Parliament. The India Rights of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2011 (RPDB) contains provisions more promising than those proposed in the Bangladeshi draft. The Indian bill contains specialised civil procedures to remedy instances of discrimination, prohibition of the failure to provide reasonable accommodations, and an affirmative duty to accommodate persons with disabilities in employment, education, and beyond.

Since discrimination cases brought under the RPDB are civil, specially constituted Disability Rights Tribunals are permitted a wide degree of latitude to provide individualised remedies, including “declaratory, mandatory, injunctive, compensatory, supervisory or any other suitable orders.” Moreover, § 33(1) read with § 33(3) of the RPDB encourage DPOs to participate actively in the tribunal proceedings, which would allow persons with disabilities and DPO leaders will be able to have a greater stake in how disputes affecting persons with disabilities are resolved vis-à-vis participation in the tribunal. These procedural innovations would be unavailable in a criminal regime.

In § 2(11)(a), the RPDB requires that accommodations be provided when “a provision, criterion or practice puts a person to whom one or more prohibited grounds apply at a disadvantage in relation to a relevant matter in comparison with other persons.” Read with §§ 2(8), 4(2), and 4(3), the foregoing section establishes reasonable accommodation not only as a ground for discrimination (in the case of its denial) but also as a remedy. These provisions allow persons with disabilities to litigate the failure to accommodate and also to receive substantive remedies that respond to their particular circumstances.

Finally, the RPDB both establishes a broad duty to accommodate by providing a readily applicable definition of “reasonable accommodation” and also creates an affirmative duty to provide specific types of accommodations that individuals might readily claim. According to § 2(30), a reasonable accommodation can be a step taken to avoid an unfair disadvantage caused by an institutional barrier, modifications to a physical feature, provide an assistive device or auxiliary aid, or provision of accessible information formats. While broad enough to encompass a diverse array of interventions and circumstances, the definition delineates four categories to facilitate determination of appropriate accommodations depending on the case. Specific obligatory accommodations are mentioned throughout the law, including the spheres of education and employment.

In conclusion, current efforts to introduce new legislation fall short of Bangladesh's obligations under international law. Moreover, the current proposals likely will not address the existing legal lacunae nor the needs and concerns of persons with disabilities going forward. There should be little mystery to complying with obligations under international law; for example, in India, the duty to accommodate persons with disabilities both in the workforce and in the education system has existed for many years even in the absence of comprehensive disability rights legislation. The Indian experience may offer many useful lessons for drafters. Indeed, the bill resulting from the concerted work of dedicated disability rights activists there hews more closely to the obligations set forth in the CRPD. There is no reason why Bangladesh should not measure up.

Hezzy Smith is the Bangladesh Program Director for the Harvard Law School Project on Disability (HPOD). HPOD is a global disability law and policy center working in Bangladesh through partners including BLAST and disabled persons' organisations.