Inside

|

What Does the European Sovereign Debt Crisis Mean for Us?

NOFEL WAHID examines ways for the Government to retain control over its economic agenda.

They say a picture can tell a thousand words. So let me try and put a thousand words to the following picture.

This is a picture of former Indonesian President Suharto signing an IMF austerity package in 1998. The man standing over Suharto's shoulder is the then-IMF Managing Director Michael Camdessus. Seeing Camdessus in his headmaster-like pose -- arms crossed, eyes fixated on the dotted line -- is disturbing, to say the least.

Camdessus, a Frenchman, famously tried to justify his pose by suggesting that his mother had taught him to stand with his arms folded as a sign of politeness. It makes you wonder if hell hath no fury like a French mother scorned by her son's lack of politeness.

This picture has come to be the defining image of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC), symbolising a loss of Asian pride and prestige. The East Asian economies emerged from the AFC determined to never rely on the IMF to deal with future crises.

A consensus emerged amongst regional policymakers that large foreign exchange reserves had to be accumulated to cushion against future balance of payments crises. And accumulate they did. By the end of September 2011, the major East Asian economies had more than US$6 trillion in foreign exchange reserves.

The East Asian economies were so successful in getting their house in order that it led the IMF to become largely irrelevant by the mid-2000s. The IMF was even considering cutting staff numbers by 15% in 2007.

But then the global financial crisis (GFC) hit in 2008, and everything changed. The IMF became hugely relevant again. This time around, it's the Europeans who need the IMF desperately.

In the last 18 months, the IMF has played a prominent role in bailing out Greece, Portugal and Ireland. There is currently intense speculation in international financial markets that the IMF will again be part of a 400 billion euro bailout package for Italy.

The story of the IMF's revival doesn't end there. In November 2011, the French President Nicholas Sarkozy announced at a European Leaders' Summit that the IMF will be monitoring the implementation of the Italian Government's austerity package, even though Italy has not borrowed any money (yet!) from the IMF. Not a single dime.

What we are seeing now is an unparalleled expansion of IMF powers. The IMF has emerged from the global financial crisis a bigger, better-resourced institution with a remit to police a broader set of policy issues, ranging from fiscal policy, financial sector bailouts to even politically-charged internal issues such as labour market policy.

So what does this all mean for us?

Firstly, we can only hope and pray that the European debt crisis does not bring about another global recession and crater our exports, precipitating a serious balance of payment crisis of our own.

A balance of payment crisis essentially happens when a country isn't earning enough foreign currency income to pay for its imports. If Europe enters into a severe recession it may have significant impacts on our exports to Europe. A European recession could also adversely impact the American economy; which, again, could affect our exports to the US.

If those risks materialise and our exports take a hit, we won't have enough foreign exchange coming in to cover our import bills. In such a scenario, we might have to turn to the IMF for help, and we know the first thing they are going to say if we do.

Slash the budget deficit!

Actually, they won't just tell us to slash the budget deficit, they will also tell us how to do it. Recent reports about how our Government has come under pressure from international financial institutions (IFIs), like the IMF and the World Bank, to cut subsidies are a case in point.

Make no mistake about it, the Government should cut subsidies. They are grossly inefficient expenditures that are more often than not rorted by special interest groups. The problem is not related to the merit of the argument (i.e. cutting subsidies), but rather the party arguing the case.

If the Government had thought of this policy idea on its own, it would have been easier to sell to the public. Sustainable policy outcomes need ownership from stakeholders, and it is very difficult to foster ownership if the policy advice is coming from overseas.

In all fairness to the IMF, it has every right to impose conditions on its loans. Has a bank ever lent you money without any strings attached? Why should it be any different for national governments?

The issue at-hand here is not about the fairness or effectiveness of aid conditionality. That's a tired old topic. A more important question is -- can the Government do more to avoid seeking help from the IFIs? How can the Government retain control over its economic agenda?

One way to bypass the IFIs would be to borrow directly from international financial markets by issuing sovereign bonds. We seem to be heading in that direction with The Daily Star recently reporting (Business section, December 2, 2011) that the Bangladesh Bank (BB) has advised the Government to issue sovereign bonds. It is a good piece of policy advice from BB, one that will have important positive implications for our economy, if implemented by the Government.

Unlike the IFIs, international investors don't dictate economic policy settings to governments. They are only interested in getting their money back, with interest. If international investors think a government's budget deficit is too big, they either won't buy that country's sovereign bonds or they will charge a higher interest rate.

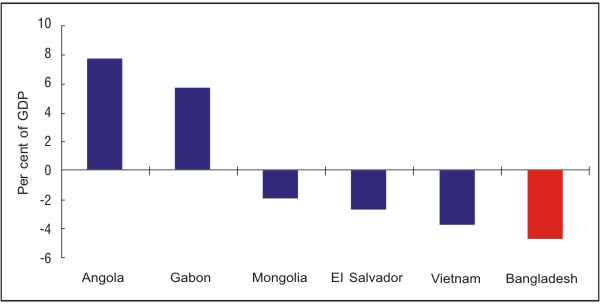

But before we get too ahead of ourselves, it is important to note that the Government isn't exactly very well-placed to start accessing international financial markets. Firstly, Bangladesh has the highest budget deficits among the five countries which share a Standard & Poor's BB- sovereign credit rating with us. The IMF projects our 2012 budget deficit to be 4.8% of GDP, which will be the worst amongst our peers (see chart below).

Chart: Projected 2012 budget deficits of BB- rated countries

BB-rated countries

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook September 2011, Standard & Poor's

With budget deficits projected to near 5% of GDP, we are -- what international investors like to call -- a 'sovereign risk'. Investors use that label when they fear that they will not get their money back if they invest in a particular country.

Moreover, with the Bangladesh Bank's strict restrictions on capital outflows, why would investors invest in Bangladesh if they can't take their money out with the click of a mouse? I know I wouldn't. BB has to do more to liberalise and open up our financial system before we can start accessing international capital markets.

Having said all that, the Government's first international bond issuance, if and when that happens, may still prove to be a success. International investors may still buy Bangladeshi sovereign bonds, but they will probably charge high interest rates. The Daily Star article mentioned earlier cited an anonymous BB official as suggesting that the Government may be able to issue sovereign bonds at an interest rate of around 6%.

That is highly unlikely. The interest rate on Bangladeshi sovereign bonds is more likely to be atleast 10%, maybe even more. Why?

The interest rate on Indian government bonds, which have a higher credit rating (BBB-) than ours, is around 9%. On the other hand, Pakistani bonds, which are rated B- (lower than ours), have an interest rate of around 12%. So it is very reasonable to expect Bangladeshi sovereign bonds to attract an interest rate of somewhere between 9-12%.

But it can be lower. If the Government reduces its budget deficit, allows the Bangladesh Bank to function more independently and rein in money supply growth to lower inflation, our sovereign credit rating might get upgraded from BB- to BBB-. That will put us on par with India and our interest rates will likely fall. A higher credit rating means lower interest rates -- it's a gospel truth as far as financial markets are concerned.

In anycase, the Government will need to be more frugal and belaboured in how it spends money borrowed from international markets. It will need to do more cost-benefit analysis of expenditure proposals and pick only the best ones. International investors can give generously without dictating policy settings, but they can also be unforgiving to the profligate. Just ask Italy.

All in all, after 40 years of solely relying on international donors and putting up with their policy diktats, it's time for us to branch out and test the international markets. We'll never know if we're cut out for it unless we try.

Nofel Wahid is an applied economist, and can be contacted at wnofel@gmail.com.