Inside

Original Forum |

| How Did We Arrive Here? -- Ali Riaz |

A Known Compromise, A Known Darkness |

| Who is Malala?` -- Tawheed Rahim |

| Intolerance -- Wearing Religion on Our Sleeves -- Ziauddin Choudhury |

| Proud to Kill -- Zoia Tariq |

“Charity vs. Social Empowerment” -- A socio-economic perspective --- Robin Abdullah Chowdhury |

Nobel Lore and Laureates |

Understanding the Causes and Consequences of Non-cooperation in Politics -- Nadeem Hussain |

My mobile weighs a ton 100 spoons but I need a knife -- Naeem Mohaiemen |

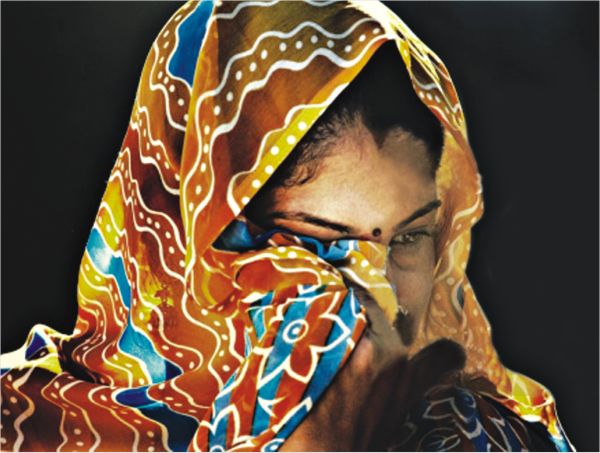

Proud to Kill

ZOIA TARIQ describes the horror of honour killings in Pakistan.

Rashida (not her real name) was worried! Wife of a factory worker and mother of a 3-year-old son, Rashida was a beautiful woman in her late twenties. Her current source of anxiety was her husband's suspicious nature and baseless allegations on her character. She was tired of being accused of having affairs with other men. After numerous arguments and violent fights, she has come to the conclusion that maybe with time, her husband would start trusting her. Or maybe when he gets a better job. Or maybe when her son grows up. Or maybe, never! Her trail of thought was interrupted when her husband entered the room. Rashida was lately feeling uneasy in his presence, especially today when she was all alone with him. A day before, sent their only child to his sister's house in another city. The conversation started with accusations of infidelity and the argument soon turned ugly as it always did. But Rashida refused to admit an act she never committed, even when her husband started to punch and kick her. Rashida threatened to leave him if he did not stop with the madness, which agitated him further and he started to strangle her. Within a few minutes, a loving mother, an unhappy wife and a vibrant woman was no more. When arrested by the police, her husband stated that he had strong suspicions that Rashida was involved in an illicit relationship, hence he had to kill her to safeguard his honour.

“A rotten finger should be amputated,” says a proverb in Dera Ghazi Khan, Southern Punjab, Pakistan.

Pakistan has one of the highest incidences of honour killings in the world. In 2011, almost 1,000 Pakistani women were murdered in the name of honour as compared to 791 reported cases in 2010. The majority of victims were married. In 92% of the cases, the reason was alleged extramarital affairs, the perpetrators being husbands in 43%, brother in 24% and other male relatives in 12% of the cases. The methods/tools used for killing were firearms, axe, strangulation, edged tool or stove burning. The age bracket of the female victim was from 15-64 years. But there is significant evidence that the above mentioned figures are quite deceptive. They reveal just the tip of the iceberg. As in almost all cases of honour killings, the perpetrator is a close family member, the murders can be easily disguised and reported as suicides or accidents. The actual number of honour killing cases is believed to be much higher than reported.

Honour killing is the extreme form of domestic violence. In Pakistan, marriage has become a contract that gives a man the right to abuse. According to a recent study, 90% of married women in Pakistan are physically, emotionally or verbally abused by their husbands. Women are considered commodities and the right to decide the fate of a commodity lies with the owner -- the male member -- of the family. Decision regarding a woman's education, marriage, property, career or even stepping out of her home and choice of dress are taken by her father, brother or husband.

In a society where the “honour” of a man is defined through the chastity and “proper” behaviour of his women, incidents of honour killings are increasing at an alarming rate. Interestingly, women are considered “honourless”. Attack on a woman's self respect, dignity and self-worth is never given importance as she is just there to protect the honour of the male members of her family.

Hina Jillani, lawyer and human rights activist has explained this phenomenon accurately. She says, “The rights to life of women in Pakistan is conditional on their obeying social norms and traditions.” The famous case of Samia Sarwar, who was killed in Hina Jillani's office at Lahore in 1999, captured the attention of the local and international media and highlighted the issue of honour killings in Pakistan. Samia, mother of two, was at her lawyer's office to seek divorce from her abusive husband, against the wishes of her father, an eminent businessman of KPK. But Samia's family would rather see her dead than living a life of her choice. This case also revealed that honour killing exists in both upper and lower income groups of the Pakistani society.

Murder in the name of honour is justified as an act to avenge the humiliation brought on the man and his family, by the victim. The reasons usually given for committing this heinous crime are alleged illicit relations, exercising the right to choose a life partner or demanding divorce, refusing an arranged marriage, marrying without family's permission, being raped over property disputes and career choices. All the reasons mentioned are believed to tarnish the honour of a man and he is obliged to punish the one who brought him shame by killing her. The general perception in society is that if a man does not teach the alleged woman a lesson, he is not “man enough” and usually becomes the laughingstock of his family and clan. Moreover, the morbid fascination of having the power to kill someone weaker than one's own self and being raised to the status of “honourable again” in the society, is a major contributing factor in the escalating cases of honour killings in Pakistan.

Honour killings, locally called Karo Kari, are seen as an effective way of safeguarding the moral and cultural values of Pakistani society. “Karo” means “black male” and “Kari”, “black female”. Family members consider themselves authorised to kill Karo and Kari once they are identified and labelled. Kari's punishment does not end even after her death. Her dead body is usually thrown away in a river or she is buried in special Kari graveyards, known as “karan jo qabarastan”. There are never any flowers on these graves and no one mourns or comes to offer prayers for the departed soul for a peaceful afterlife.

The most horrifying aspect of honour killings in Pakistan is not the act itself, but the attitude and support of the society for it. It is perceived as a battle of good and the bad. The hero being the man who kills his wife in the name of honour. Not only society blames a woman in such cases, there is a general belief that she “deserved” it as she was attempting to challenge the norms. It is perceived as justice and a lesson for other women in the family and society nurturing such “objectionable” thoughts. Even the language used in media reports and Police FIR for honour killings is not gender-sensitive and even implies that the murder was justified. There is a soft corner for the man, the killer . On the reports of honour killings in media, people merely shake their heads and blame the “westernisation” of our women that leads to such horror. No one blames the killer. “He did what he had to do” is the unanimous sentiment. When a woman in Pakistan asserts her right to choose a marriage partner, resist domestic abuse or walk out of a violent relationship, she is resisting to conform to the moral values of the society. Hence the society reacts by labelling her Kari (Sindhi) or Siakari (Baluch). This is especially true for the rural areas of Pakistan where honour killings have total support of the people. This explains why no concrete measures have been developed and taken up by the people and the State to counter this horrifying trend.

According to a women's rights activist Tahira Abdullah, almost 77% of honour killing cases end in acquittal of criminals. Laws like Hudood, Qisas and Diyat have widely contributed to the rising number of honour killings in Pakistan. Even if guilt is established and the killer is proven guilty, the laws of Qisas and Diyat facilitate and protect the murderer from punishment. Under the Qisas and Diyat laws of Sharia, offences like honour crimes are compoundable (open to compromise as a private matter between two parties) by providing Qisas (retribution) or Diyat (blood money). The family of the victim (which in most cases is also the family of the killer) can forgive the murderer in the name of God without receiving any compensation or Diyat, or compromise after receiving Diyat.

But no one mentions the criminality and the horror of killing a woman in the name of honour.

Near a small village of Sindh, there is an unmarked grave in the far corner of a large graveyard. No one comes here to offer prayers. A tiny pink rose has sprouted out of this ground. Pink was Sakina's favourite colour. Sakina (not her real name), the 16-year-old, killed on suspicion of having an affair with the local school master, buried in this spot. She is resting, but not in peace. She wants her brother to be punished for taking away a life so young and full of dreams. She is waiting for justice. It will be a long wait . . .

Zoia Tariq is Editor-in-chief, ZEST, Pakistan and can be reached at zoiatariq@gmail.com.