Inside

Original Forum |

| 2012: Lessons Learnt |

Bangladesh in 2013: Dangling

Between Hopes and Reality |

| Beyond the Rage -- Sushmita S Preetha |

| Law, Culture and Politics of Hartal -- Dr Zahidul Islam Biswas |

| Victory's Silence -- Bina D'Costa |

Can Children Deny Maintaining their Elderly Parents? --- Mariha Zaman Khan |

Let's Talk about Domestic Violence! -- Ishita Dutta |

An Unfinished Story -- Deb Mukharji |

| A Tale of Political Dynasties -- Syed Badrul Ahsan |

| “Bangladesh Brand”: Exploring potentials -- Makluka Jinia and Dr. Ershad Ali |

| Give Dignity a Chance: Two observations and five takeaways -- Lutfey Siddiqi |

| Diplomatic Snubs and Put-downs -- Megasthenes |

| Hay Festival: International Interactions of Literature, Culture and Creativity -- Farhan Ishraq |

| Endnote -- Kajalie Shehreen Islam |

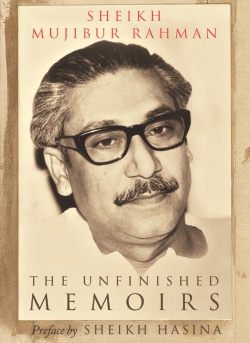

An Unfinished Story

DEB MUKHARJI traces the life of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman through his unfinished memoirs.

The Unfinished Memoirs of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman were written while the author was a political prisoner between 1967 and 1969. The period covered is from his school days till 1955 when, in his mid-thirties, he was already established as one of the most dynamic politicians of East Pakistan and an uncompromising champion of the rights of his people

Sheikh Mujib has been acknowledged as the Father of the Nation in Bangladesh and, as his daughter Sheikh Hasina says in the Preface, his assassins 'managed to mark the forehead of the Bengali nation indelibly with the stamp of infamy'. The years of triumph and tragedy still lay ahead when the memoirs were written, but they provide invaluable insights into the making of the man and perspectives on the fractious and turbulent politics of Bengal -- and Pakistan -- for nearly two decades.

Owing to illnesses in childhood, Mujib was a late entrant in school and thus older than his classmates. “A significant event of my life occurred”, when in 1938 the then chief minister of Bengal, Fazlul Haq, and labour minister Shaheed Suhrawardy visited Gopalganj where Mujib had been active in organising a reception for them. The Hindu boys stayed away, apparently under instructions of the Congress party. “The news surprised me since we didn't treat Hindus and Muslims differently then. I was very friendly with the Hindu boys. We used to play, sing and roam the streets together.” The seeds of separate identity had been sown, to be nurtured further when a good Hindu friend was chastised at home for inviting Mujib inside. Many Hindu friends “wouldn't invite me into their houses because their families feared I would pollute them.” After the reception at the school Suhrawardy noted young Mujib's name and address and was later to write to him to stay in touch. Thus began an association between mentor and pupil that was to last till the former's death.

The 'Hindu' leaders for whom Mujib has unqualified respect are Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. As a teenager he had imbibed dislike of the English from Bose's politics and, years later, his heart is with Netaji as he hopes that he might militarily liberate India, but then wonders if this would be good for the Muslims of India. For by then he believed “with my heart and soul that Muslims would be wiped out in an undivided India”. And his mentor Suhrawardy “believed that had Das lived longer he would have eliminated the causes of Hindu-Muslim conflict” (S.A. Karim: Sheikh Mujib, Triumph and Tragedy). Bangladeshi friends told me in Dhaka in the 1970s that if Das had lived and been able to guide Congress politics, there may not have been a partition of India.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was clear as to his own identity: “We Bengali Muslims have two sides: one is our belief that we are Muslims and the other that we are Bengalis.”

By the time he moved to the Islamia College in Calcutta “I had become deeply involved in politics…all I could think of was working for the Muslim League and Muslim Student's League. I believed that we would have to create Pakistan and that without it Muslims had no future in our part of the world.” Religion, he mentions in passing, was also used for promoting the idea of Pakistan. The Bengal famine provided an opportunity to propagate the idea of Pakistan and engagement in relief met the “twin objective of providing relief and popularizing Pakistan”. “From this time on,” recalls Mujib, the Muslim League of Bengal broke into two factions, one “progressive and the other reactionary…we wanted to make the Muslim League the party of the people and make it represent middle-class Bengali aspirations”, while the other represented the “landlords, moneyed men, and Nawabs and Khan Bahadurs”. This innate distaste for elite privileged classes disconnected from the people would one day bring about the formation of the Awami League.

Elected a councillor of the Muslim League in 1943, Mujib saw the intense infighting within the League which would have included the marginalisation of Fazlul Haq after he had been induced to move the Lahore (“Pakistan”) Resolution in 1940 and the subsequent substantive entry of the Muslim League in Bengal politics. In April 1946, Mujib attended the League's Council meeting in Delhi where resolution changed the plural of Muslim majority 'states' of the Lahore resolution to the singular 'state'. (NB This may have been done also at Madras) The lone Bengali objection to this change went unheeded and the issue was obfuscated as “we were told that the Lahore Resolution had not been altered and that this resolution was the result of that particular convention”. Throughout this period, Mujib retained unflinching faith in the guiding hand of Jinnah for “Muhammad Ali Jinnah knew the Congress and British government well and it wasn't easy to deceive someone like him”.

Throughout his reminiscences, Mujib honestly recalls his struggle to keep up with his studies and impending examinations which invariably came in the way of his political activities, only being prodded by his father to pass his exams. He also admits with disarming candour to his perpetual state of impecuniousness which often distressed his wife Renu (Begum Fazilatunnesa). His father, Sheikh Lutfar Rahman, usually bailed him out. At a later date he declines his father's offer to sell some land and send him to England to study for the bar, declaring that he had no wish to become a lawyer and make money.

It is generally accepted that the Calcutta riots on and after Direct Action Day on August 16, 1946, called by Jinnah to demonstrate support for the creation of Pakistan, and the blood-letting that followed in Noakhali, Bihar and many other parts of India made partition inevitable. The role of Shaheed Suhrawardy, then chief minister of Bengal and holding the home portfolio, has remained under adverse scrutiny. Mujib was in Calcutta at the time and helped in rescue and succour to Muslims in the city, as also on occasions, Hindus. He freely acknowledges that many Hindus helped Muslims in distress at risk to themselves and vice versa. But his account is essentially Muslim centric, absolving the government of negligence or worse, and asserting, “I can vouch though that the Muslims were not at all ready for the riots.” He acknowledges Gandhi's calming influence, but was to leave quietly for him a packet containing photographs of the mutilated bodies of Muslim men and women as “we wanted the mahatma to see how his people had been guilty of such crimes and how they had killed innocents”.

It is generally accepted that the Calcutta riots on and after Direct Action Day on August 16, 1946, called by Jinnah to demonstrate support for the creation of Pakistan, and the blood-letting that followed in Noakhali, Bihar and many other parts of India made partition inevitable. The role of Shaheed Suhrawardy, then chief minister of Bengal and holding the home portfolio, has remained under adverse scrutiny. Mujib was in Calcutta at the time and helped in rescue and succour to Muslims in the city, as also on occasions, Hindus. He freely acknowledges that many Hindus helped Muslims in distress at risk to themselves and vice versa. But his account is essentially Muslim centric, absolving the government of negligence or worse, and asserting, “I can vouch though that the Muslims were not at all ready for the riots.” He acknowledges Gandhi's calming influence, but was to leave quietly for him a packet containing photographs of the mutilated bodies of Muslim men and women as “we wanted the mahatma to see how his people had been guilty of such crimes and how they had killed innocents”.

As with many others, Sheikh Mujib had hoped for a united Bengal with Calcutta as its capital. Even in a divided Bengal, Mujib expected Darjeeling and Assam (then including the north-east) to be merged in East Bengal. Mujib is surprised that districts in Bengal were sliced according to communal demography, forgetting that seeking security in being in a majority is not a one way street. There is dismay that greater efforts were not made to include (Hindu majority) Calcutta in Pakistan even though it had been “built by the money derived from the people of East Bengal”. Distress that Muslim majority Murshidabad has been awarded to India is not matched by knowledge that Hindu majority Khulna has gone to Pakistan, as also Buddhist Chittagong Hill Tracts despite their pleas to be included in India. At Partition, Suhrawardy decided to stay back in Calcutta for the 'hapless Muslims', but asked Mujib to go back to East Pakistan to ensure communal harmony and prevent the exodus of Hindus, for any consequent counter migration of Muslims would 'be catastrophic' for Pakistan.

But the Pakistan that emerged was not the Pakistan of his dreams and struggles. The first jolt came on the question of language when even the revered Jinnah came to Dhaka to announce that Urdu shall be the language of the country. The issue simmered till it boiled over with the killing of students in Dhaka on February 21, 1952. The battle had been joined. Henceforth, language would divide Dhaka and Karachi, and the chasm would deepen with increasing economic exploitation of the East. Mujib would spend much of the following years in prison.

Mujib's account of the early 1950s lay bare the manipulative politics of the ruling coterie from West Pakistan. He complains bitterly of the betrayal by Bengalis in the government under the influence and domination of bureaucrats. Mujib was no pushover. Before the elections he 'threatened to peel off the skin of the chief minister, Nurul Amin, and turn it into a pair of slippers…because it was so thick' ( S.A. Karim: ibid). In 1954 the United Front swept away the Muslim League in the provincial elections, to be dismissed within weeks under trumped up charges. While imposing governor's rule in East Pakistan, prime minister Mohammad Ali called Fazlul Haq a traitor and Mujib a rioter. None of the leaders protested and of the 18 or so ministers Mujib was the only one in prison. He comments with contempt, “they would be sure to flee to their burrows if the police flourished their sticks and guns. If they had faced opposition, the oppressors would have thought a thousand times before ever daring to take action against Bengalis as a whole.” Pakistani leadership perhaps took their cue from this episode when deciding on their crackdown in March 1971, but were confronted by a different Bangladesh.

Mujib is critical of Pakistan joining military blocs. “The newly created state of Pakistan should have followed a neutral and independent foreign policy. We should not have made enemies of any country…it should have been a sin for us to even think of joining any military bloc since we should help maintain peace in the world and since peace is imperative to ensure the economic welfare of the people of a country.”

The unfinished memoirs of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman conclude with 1955 as he plans a no-confidence motion against Fazlul Haq, the leader of the United Front, for exceeding his mandate. The motion was to fail narrowly due to manipulations, but it speaks volumes for the principles of a 35-year-old taking on a living legend of Bengal politics.

The image of Sheikh Mujib that emerges from the Memoirs is that of a man who knew no fear and had absolute commitment to the welfare of his people. A man also perhaps so trusting and led at times so much by his emotions that he could easily be betrayed. He paid with his life for these qualities, but left behind a new name on the global map.

Deb Mukharji was a member of the Indian Foreign Service (1964-2001). He served in Islamabad (1968-1971) and Dhaka (1977-1980 and 1995-2000). He was co-convenor of the Indo-Bangladesh Track II Dialogue from 2004-2007. He has anchored Bangla television programmes on Indo-Bangladesh issues.