Law analysis

Prosecuting the 1971 perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes

Dr. M. Shah Alam

|

Munir uz Zaman/ Driknews |

Genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes are the most heinous crimes under international law as well as under specific national laws of many countries. Since the end of the Second World War and the establishment of the United Nations, many international tribunals, especially formed for the purpose, have prosecuted, convicted and punished the perpetrators of these crimes, committed in different parts of the world. Many national courts have also tried them either applying international law or national law, or both. Such trials are still taking place.

Elements of these crimes have been elaborately defined and described in many international instruments including the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide 1948, statutes of the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals 1946, Geneva conventions on laws and customs of war 1949, statutes of international criminal tribunals on the crimes committed in former Yugoslavia and Rwanda 1993-94 and the Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998. Amongst the national enactments, the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act 1973 of Bangladesh stands prominent. Besides international tribunals, the perpetrators of these crimes as hostis humanis generis (enemies of mankind), irrespective of their nationality and the place of commission of the crimes, are also triable by any legally formed domestic court anywhere in the world under universal jurisdiction.

Provisions for punishment of these crimes form the core of international criminal law, substantial part of which is now strongly entrenched in the Statute of the International Criminal Court. Mankind's endeavour and drive to fight and prosecute the crimes are part of its collective efforts to establish international rule of law as well as rule of law in individual countries. It is, therefore, the obligation of both international and national communities to bring the perpetrators of these heinous crimes to justice.

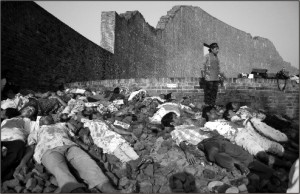

There are overwhelmingly strong evidences that the above crimes were committed by Pakistani regular and auxiliary forces during the Bangladesh War of Liberation in 1971 (anti-liberation forces call it civil war which, however, in no way diminishes the criminal liability of the perpetrators). In terms of number of people killed (about three million), women raped (two hundred thousand) and persons forced to flee their homes to turn refugees (ten million took shelter in India), the above crimes undoubtedly rank first after Nazi holocaust during the Second World War, followed by genocide committed by Khemr Rouge regime of Pol Pot in mid-seventies in Cambodia, brutal elimination of about one million Hutus by the Tutsis in Rwanda in the late eighties and the ethnic cleansing of the Muslims by the Serbs in Bosnia in the early nineties of the last century. While these latter crimes have been prosecuted, or are being prosecuted, it is preposterous that the crimes committed in Bangladesh during 1971 have remained to date with impunity.

It is not only the failure of independent Bangladesh after 1971, but also the international community in the body of the United Nations that it could not secure the trial of the perpetrators of those crimes. International and regional politics, and after the tragic killings of 1975, national politics, posed impediments for the trials. However, prosecution of crimes is never time-barred. On going trials in Cambodia and Chile, and trials of the accused of atrocities in the Second World War long after their commission, are glaring examples.

Recently (December 19, 2007) the former Army Chief of the Military Dictatorship of Argentina (1976-83) Christiano Nicolaides along with others has been sentenced by a domestic court to twenty-five years of imprisonment for atrocities committed during its regime. More recently, an Italian court issued arrest warrant on a number of former military leaders of some Latin American countries who allegedly committed atrocities against many innocents, amongst them Italian nationals, during their dictatorial regimes in the late seventies and eighties.

Astonishing thing about the crimes committed in Bangladesh in 1971 is that they mostly remained beyond the knowledge of the international community, which could never imagine the full scale and dimension of the crimes committed. At a seminar in Wellington in April, 2004, on a personal query during one of the recesses, Justice Blade, a judge of the International Criminal Court, told me that he had little knowledge of 1971 genocide in Bangladesh. To my great surprise he added that his daughter who was doing higher research on genocide, he believed, also did not possess sufficient information about the genocide in Bangladesh of the scale and dimension that I narrated to him.

This is mainly attributable to the position taken at that time by the United States in relation to the events in erstwhile Pakistan, and the political, diplomatic and media camouflage they created around them. They projected the happenings as civil war and hence internal affairs of Pakistan in the context of India-Pakistan rivalry where India lent strong support to the Liberation War of Bangladesh, and ultimately leading to India-Pakistan war, out of which emerged independent Bangladesh.

Later, India's cautious diplomacy and eagerness to ease tensions with Pakistan, Simla Agreement and Bangladesh's inability to overcome India's approach towards the issue, accompanied by ever imposing US policy and politics, obfuscated the situations to prevent the crimes in Bangladesh from being exposed to international community in their true colour and dimension. International community could little be mobilized for trial of these crimes. This also impacted the national efforts for the trial. This is unprecedented that while the Liberation War itself drew sufficient attention and formidable support from international community, crimes committed by occupation forces remained largely unaccounted.

Notwithstanding the above, the newly born State of Bangladesh took some concrete steps to prosecute the perpetrators of the crimes. The Bangladesh Collaborators (Special Tribunals) Order 1972 was proclaimed to prosecute those who collaborated with Pakistani occupying forces to perpetrate atrocities. Many were prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to imprisonment.

The Bangladesh Parliament adopted the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act in 1973. This was preceded by the adoption of the First Amendment to the Constitution of Bangladesh, which purported to clear the way for the prosecution of the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes by stipulating that provisions of fundamental rights in the Constitution may not be used for their protection.

However, these moves were visibly obviated by India's stand on the possible trial of Pakistani war criminals as well as by internal and external political development. Political change-over in 1975 completely stopped whatever remained of the moves to prosecute, or even undid what the pre-August 1975 government did to punish the criminals.

After August 1975, anti-liberation forces again surfaced in national politics, and even shared power with BNP, the party which played the decisive role in rehabilitating them. Politics by then had undergone so much metamorphosis that even Awami League, the party leading the Liberation War and the main victim of 1975 change-over, which returned to power for five years in 1996, could not or did not effectively pursue the issue of the trials. International concern and mobilization seemed to have been buried by national non-action.

Nonetheless, social hatred for the criminals and demand for their trial within Bangladesh remained and lay dormant, with occasional outbursts and clamours for trial, movement spearheaded by a martyr's mother Jahanara Imam being prominent amongst them. Different social groups especially freedom fighters raised the issue of the trials. Many research and pro-liberation activist organizations were established to conduct intensive investigation to find the actual dimension of the massacre, which made the demand for trial stronger.

There have also been studies and research abroad especially initiated by Bangladeshi expatriates. On December 9, 2007, a seminar on 1971 genocide in Bangladesh was held in the Department of Holocaust and Genocide Studies of the University of Keane at New Jersy. It was announced at the seminar that a full course on Bangladesh genocide at Masters level would be offered at the Department.

Socio-political forces for the trial long suppressed in different ways have been burning inside and longed for a vent to their pent-up feelings. Overwhelmingly seditious comments recently made by some publicly identified collaborators worked as catalyst for the people at large and many organizations to mobilize, organize and appeal to the incumbent non-party (and non-political) government to take the initiative for the trials.

It is very encouraging that the people of different and even opposing political shades have got together to demand the trials of the perpetrators of genocide and war crimes. There are valid reasons to believe that the forces demanding the trials have great potentials to multiply and intensify. That which was difficult in a situation of party politics is proving easier now. This is expected to continue even after the return of party politics.

National demand for trial rising and any government convinced of such demand and willing to respond positively, there is no dearth of laws and evidences to prosecute the accused. Trial is necessary for the rule of law, and to relieve the nation of a moral and legal burden of non-trial which increasingly hangs heavy on the nation. With this burden the nation has advanced little; with this burden the nation will advance little.

The most effective way for the trial would be to commission and invoke the 1973 International Crimes Act. The tribunals established under the Act would be capable of easily addressing the procedural hazards of criminal litigation to facilitate expeditious justice. In fact, First Amendment and the 1973 Act cleared the way for that. Alternatively, the government willing or the people compelling the government to so will, it is possible to seek UN assistance to establish an international tribunal for the trial under international law, as it has been now done in Cambodia.

In invoking the 1973 Act and setting up tribunals, or in seeking UN assistance to establish an international tribunal, the government role is supreme and would be most effective. However, it is not impossible to set the mechanism of prosecution into operation by private initiative by way of instituting murder cases against individual or group killers, or by invoking universal jurisdiction of the existing domestic courts for the prosecution of international crimes.

The government can form a special investigation commission to elicit complaints and evidences of crimes to prepare for the prosecution. Facts and evidences being clearly on record, law and procedure would never be lacking to provide justice. There may be practical difficulties in apprehending the accused living outside the territory of Bangladesh, but there are many who are living inside.

There is no use now blaming one another for the past lapses in the question of the trial, which might have resulted from various political constraints and compulsions. The lapses need to be rectified. There is a great need for networking and coordination, accompanied by more research and investigation, amongst various national and international groups who are mobilizing all possible forces to intensify the demands for trial. Recent moves by the sector commanders of the Liberation War are indeed encouraging for the nation. These efforts ought to continue until a government, present or future, undertakes appropriate steps for the trial. The trial shall have to take place, today or tomorrow.

The writer is Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Chittagong