Fact file

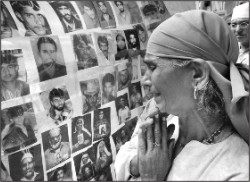

Remembering those who disappeared

Sunday 30 August marks the 26th International Day of the Disappeared. Every year, Amnesty International, along with other NGOs, families associations and grassroots groups, remembers the disappeared and demands justice for victims of enforced disappearances through activities and events.

Sunday 30 August marks the 26th International Day of the Disappeared. Every year, Amnesty International, along with other NGOs, families associations and grassroots groups, remembers the disappeared and demands justice for victims of enforced disappearances through activities and events.

Governments use enforced disappearance as a tool of repression to silence dissent and eliminate political opposition, as well as to persecute ethnic, religious and political groups.

More than 3,000 ethnic Albanians were the victims of enforced disappearances during the armed conflict in Kosovo in 1999. These were at the hands of the Serbian police, paramilitary and military forces. More than 800 Serbs, Roma and others were abducted by armed ethnic Albanian groups. Some 1,900 families in Kosovo and Serbia are still waiting to find out what happened to their relatives.

Enforced disappearances often take place in connection with counter-insurgency or counter-terrorism operations. Chechnya, which tried to secede from the Russian Federation in 1991, has since been ravaged by two armed conflicts and a counter-terror operation. Both Russian federal forces and Chechen law enforcement officials have been implicated in enforced disappearances, which run into the thousands.

In the Philippines, over 1,600 people have disappeared since the 1970s, mostly during counter-insurgency operations against left-leaning or secessionist groups.

James Balao, an Indigenous Peoples' rights activist and researcher, disappeared in September 2008, while driving to visit his family in La Trinidad, Benguet province.

He was stopped and bundled into a white van by armed and uniformed men claiming to be police officers. Eye-witnesses signed affidavits describing his capture and are now in hiding in fear of being persecuted.

The families and friends of those who disappear are left in an anguish of uncertainty, unable to grieve and go on with their lives. Chief Ebrima Manneh, a Gambian journalist, was arrested in July 2006 for trying to publish a BBC article critical of the Gambian government. His whereabouts remain unknown despite a landmark ruling by a West African regional court ordering the Gambian government to release him and pay damages. Ebrima Manneh's mother says she finds it hard to enjoy anything because her son is constantly on her mind. The family told Amnesty International that they felt increasingly isolated because other people were afraid to associate with them. They also face hardship because the depended on Ebrima Manneh's salary.

To combat enforced disappearance, in 2006 the UN General Assembly adopted the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Once entered into force, the Convention will be an effective way to help prevent enforced disappearances, establish the truth about this crime, punish the perpetrators and provide reparations to the victims and their families

The Convention's definition of enforced disappearance is:

"The arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons, or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law."

The Convention addresses the violations linked to an enforced disappearance and the problems facing those who try to investigate and hold perpetrators to account. It also recognizes the families' rights to know the truth about the fate of a disappeared person and to obtain reparations.

The Convention obliges states to protect witnesses and to hold any person involved in an enforced disappearance criminally responsible. It also requires states to institute stringent safeguards for people deprived of their liberty; to search for the disappeared person and, if they have died, to locate, respect and return the remains.

The Convention also requires states to prosecute alleged perpetrators present in their territory, regardless of where they may have committed the crime, unless they decide to extradite them to another state or surrender them to an international criminal court.

A Committee on Enforced Disappearances will oversee the Convention's implementation and will review complaints from individuals and states.

The Convention is now only a few ratifications away from entering into force. Amnesty International calls on all governments that have not done so already to ratify the Convention as soon as possible. Ratification will send a powerful signal that enforced disappearances will not be tolerated and will give those searching for their loved ones a much needed new tool.

Source: Amnesty International.