Law campaign

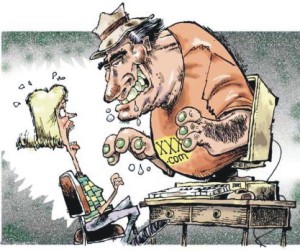

Web of Terror

Cyberstalking and the law

Shahmuddin Ahmed Siddiky

WHILE it is difficult to deny the massive impact the internet has had on our lives, the cyber world can be a frightening place. We live in an era where the web is a mirror of the real world, and consequently it contains electronic versions of real life problems. Cyberstalking, for instance, has become a major cause of concern globally. To make the situation worse, an alarming portion of internet usage remains unregulated by law.

Not many people are acquainted with the concept of cyberstalking. Even where they are, it is almost always the case that they do not appreciate its gravity. It is easy to be fooled into thinking that since it does not involve physical contact, it is not as serious as physical stalking. As the internet becomes an even more integral part of our personal and professional lives, stalkers can take advantage of the ease of communications, the net's intrusive capabilities, as well as increased access to personal information. Moreover, the ease of use and non-confrontational, impersonal, and sometimes anonymous nature of internet communications encourage such acts all the more. Whereas a potential stalker may be unwilling or unable to confront a victim in person, he or she may have little hesitation sending harassing or threatening electronic communications to a victim, using some virtual alias as a shield. Finally, as with physical stalking, online harassment and threats can often develop in more serious behaviour, including physical violence.

Not many people are acquainted with the concept of cyberstalking. Even where they are, it is almost always the case that they do not appreciate its gravity. It is easy to be fooled into thinking that since it does not involve physical contact, it is not as serious as physical stalking. As the internet becomes an even more integral part of our personal and professional lives, stalkers can take advantage of the ease of communications, the net's intrusive capabilities, as well as increased access to personal information. Moreover, the ease of use and non-confrontational, impersonal, and sometimes anonymous nature of internet communications encourage such acts all the more. Whereas a potential stalker may be unwilling or unable to confront a victim in person, he or she may have little hesitation sending harassing or threatening electronic communications to a victim, using some virtual alias as a shield. Finally, as with physical stalking, online harassment and threats can often develop in more serious behaviour, including physical violence.

Cyberstalking is a relatively new concept, and in Bangladesh, as in most parts of the world, the hand of law has yet to reach that far. It is thus not surprising that no specialised law exists in Bangladesh to this effect. Nonetheless, the victim has, at his disposal, some remedies that can be obtained indirectly.

Tort law, through its remedy of injunctions (under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, for temporary injunctions and the Specific Relief Act, 1963, for other injunctions), could well be availed by the victim (either real-world or online) against a stalker. The apprehended damage must involve imminent danger of a substantial kind or injury that will be irreparable.

It is also possible to bring a civil action against the stalker. This allows the victim to sue him or her for any damage they have done for emotional harm, etc., and may entitle the victim to exemplary damages.

However, they are unlikely to be as effective in practice. Firstly, the sheer expenses involved could easily discourage litigation. Further, it is necessary to know the identity of the stalker to be able to institute the proceedings. This is a major problem since in most cyberstalking cases the stalker remains anonymous. In addition, the onus is on the victim of the stalking to lead evidence and make out a case without the aid of the law enforcement infrastructure for investigation. This would also be at a time when he/she is undergoing the harrowing experience of being stalked. This is more so in a case of cyberstalking where unless the victim is technologically aware he/she will not be in a position to make out a good case with sufficient evidence of harassment in the virtual world.

Under criminal law, proceedings can be brought under sections 323 and 325 of the Penal Code for voluntarily causing hurt or grievous hurt. Section 319 defines “hurt” as follows: “Whoever causes bodily pain, disease or infirmity to any person is said to cause hurt”. The crucial words here would be “disease” and “infirmity”, since neither is qualified with the word “physical”. Stalking incidents may only leave mental and psychological scars on the victim without causing any sort of physical manifestation. Could these be brought under “causes… disease or infirmity”? This is a tricky question for the judiciary. It is important to bear in mind that judicial precedent in this area is almost non-existent. Also, one must remember that judges may be reluctant to tread so far on a path that has rarely been tread upon.

Alternatively, section 351 (which deals with “assault”) of the Penal Code could be invoked. This is dependant on the definition of “criminal force” found in section 349 since it states, “Whoever makes any gesture, or any preparation intending or knowing it to be likely that such gesture or preparation will cause any person present to apprehend that he who makes that gesture or preparation is about to use criminal force to that person, is said to commit an assault”.

However, the real issue is that of defining the phrase “person present”. Does this have to be physical presence? One would assume so considering that the victim must have seen the “gesture or preparation” as a result of which he/she is apprehensive of the application of criminal force. Thus, in the case of many stalking incidents such as obscene/blank phone calls as well as cyberstalking, this section would not apply directly, as it contemplates the presence of both the accused and the victim at the same place at the same time. The context does change a bit in the age of instantaneous communication of the telephone, the fax and the internet, and their potential misuse. The Penal Code was drafted in 1860. Does the meaning we attribute to the word “presence” then need some updating? Perhaps virtual presence should be brought within the definition?

In conclusion, the law has yet to develop in this field. In the meantime, we can hope that the current inadequacies would compel the lawmakers to take some steps in this direction.

The writer is a Barrister-at-Law.