Reviewing the views

Contempt of court Vs freedom of press

M Rafiqul Islam

|

mediabistro |

The Supreme Court on 19 August 2010 has sentenced the acting editor of Amar Desh to 6 months jail for contempt of court arising from a published report questioning the integrity and political neutrality of judges. This decision once again exposes the uneasy co-existence of the law governing contempt of court and the press freedom. In contrast though, the High Court on 22 March 2007 rejected a petition for contempt proceedings against the Daily Manabzamin, which also doubted the qualifications, honesty, and impartiality of judges. But its editor received jail term in a prior contempt case (Cassette Scandal) in May 2002. Justice Naimuddin Ahmed, a retired HC judge, was also made a party to the Cassette Scandal case for his allegedly contemptuous statement published in two national dailies. His statement underscored the lack of judicial accountability for failure to issue a suo motu rule in such a serious allegation of telephonic conversation between a judge and a convict. The HC made a ruling directing the retired judge and the two newspapers that published the impugned comment to show cause as to why contempt proceedings would not be drawn against them for scandalising the judges and the court through public remarks. Justice Ahmed and the newspapers were acquitted. But the chief editor of one of the newspapers was punished with jail term and fine. These examples tend to suggest that the law of contempt of court warrants reform for specificity to ensure uniformity and certainty.

There is no compelling reason to believe that the general public should always be happy with the role of the judiciary and its judges. There is no statutory bar on the public and press criticism of judges and their judgments, though such criticism is rare for a variety of reasons. One such reason is the fear of contempt of court action. The essence of contempt is an action or inaction amounting to an interference with or the obstruction of the due administration of justice. The objective of the contempt proceedings is to protect the prestige, dignity, and authority of the court (Onish v Dulla Mia, 1969 AIR 214; State v Abdur Rashid, 1964 PLD Dacca 241; Moazzem Hossain v State 1983, 35 DLR 290; Abdul Karim Sarkar v State 1986, 38 DLR AD 188). Freedom of thought, conscience, and speech is a fundamental right under various international human rights instruments (such as ICCPR of which Bangladesh is a party) and under Article 39 of the Bangladesh Constitution subject to reasonable restrictions, which include contempt of court. The Contempt of Court Act 1926, as adopted in Bangladesh from British colonial administration in India, does not define the expression “contempt of court” nor does it identify the acts constituting such contempt. This vacuum often enables a court to exercise its contempt jurisdiction widely with a great deal of discretion.

There is a pertinent body of case law that has developed the principles and objectives of contempt action, particularly when the public criticism of judicial conduct constitutes an act of contempt of court. The Lahore HC held that judges and courts are open to public criticism. No court would treat reasonable arguments against any judicial act as contrary to law or the public good as the contempt of court. The court further observed that justice does not live in seclusion and in the protection of cloisters; it is an essential part of practical life and should therefore be open to fair comment in State v Abdul Latif (1961) PLD Lah 51. It also held that criticism of the conduct of judges, which cannot possibly have the tendency to obstruct or interfere with the administration of justice, is not contempt of court in Edward Snelson v Judges (1964)16 DLR FC 535. The Bangladesh SC held that a court is to suffer criticism made against it and only in exceptional cases of bad faith or ill motive should it resort to the law of contempt in Saleem Ullah v State (1992) 44 DLR AD 309. The SC also recognised freedom of speech and expression entrenched in Article 39 of the Constitution as a right to express one's own opinion absolutely freely by spoken words, writing, printing, painting, or in any other manner in Dewan Abdul Kader v Bangladesh (1994) 46 DLR 596.

In Australia, all judicial functions are open to public scrutiny. The CJ of South Australia observed: “No judge worthy of the judicial officer will resent or fear such accountability. To the contrary, the judiciary should welcome it, even when it is misused” (Journal of Judicial Administration vol. 11 at 169, 174). Lord Denning justified the freedom of press as a watcher of the judicial functions: “In every court in England you will find a newspaper reporter. He notes all that goes on and makes a fair and accurate report of it. He is the watchdog of justice. The judges will be careful to see that the trial is fairly and properly conducted if he realises that any unfairness or impropriety on his part will be noted by those in Court and may be reported in the press. He will be more anxious to give a correct decision if he knows that his reasons must justify themselves at the Bar of public opinion” (Denning, The Road to Justice, 1955, p 64).

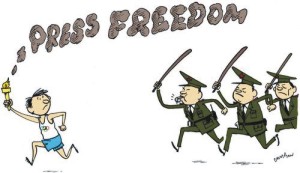

The press could be the best watchdog to ensure judicial accountability to the public. The degree of public confidence in the judiciary is contingent upon the public perception of the integrity and transparency of its decision-making process. The freedom of press requires fairness and ethical standard in discharging its duty especially in reporting on the affairs of the judiciary. If the press plays a strictly responsible role in reporting on the prevalent impropriety of the judiciary, it would be of much help to warn the judges to be honest and sincere. Judges are perceived to be persons of high integrity and impeccable character. They are expected to adopt exceptionally high moral standards. Press criticisms may help them in the reconsideration of a decision on appeal. Freedom to criticise and analyse judgments goes a long way in upholding the fundamental right to the press freedom.

It is imperative that Bangladesh respects the press as an effective means of the public scrutiny of judicial conducts. Some form of legal regulation may be necessary to prevent irresponsible reporting that may damage the image of the judiciary. The judiciary appreciates the press publicity of its positive role in upholding the constitutional guarantees. It must also appreciate press criticism of judicial misconducts, if any. Attempts at strict regulation of the press through contempt proceedings under any dubious circumstances are likely to raise public concern. The judiciary need not be obsessed with contempt actions in an attempt to insulate itself from press criticisms. The essence of the law of contempt is to preserve the public confidence in the judiciary (Abdul Mannan v State 1997, 29 DLR 311). Continuous practice of judicial immunity from public criticisms through contempt actions may considerably diminish public confidence in the judiciary.

The law of contempt has undergone changes in many countries. India has enacted its new Contempt of Court Act 1971, which defines the actions that constitute contempt (s2) and provides that fair criticism on the decided cases is not a contemptuous conduct (s5). The UK has enacted a new law in 1981 that emphasises “good faith” in respect of publications (The Contempt of Court Act 1981, s5). The outdated law of contempt in Bangladesh calls for major amendment or may be replaced by a new law, defining the actions or omissions that constitute such contempt, having regard to the public rights to know and criticise the judicial functions constructively. A crucial criterion should be that if a press report is found true and it provides ample clues to detect a judicial misfeasance, the court may ignore the contempt issue in the greater interest of transparency, accountability, and natural justice. Responsible public criticisms of the judiciary expressed through the media may force it to be more careful, rational, and fair in decision-making. The judiciary benefits from such criticisms, which in effect augment its public image. In the process, both public confidence in the judiciary and freedom of press are maximised. It is erroneous to view press criticisms inimical to judicial independence. Judicial independence and accountability are mutually complementary in that the former endures if the latter strengthens.

Good governance calls for a balanced judiciary, which is both independent and accountable in exercising its judicial powers. Judicial independence is not a privilege for judges. It is rather a means to protect the citizens' freedom and rights in law. Judicial independence devoid of popular approval is hollow and self-defeating. The revolutionary progression of information technology has led to the informed thinking of the people on various pivotal issues affecting their daily life. This process has rendered these issues mass-oriented and created collective public interest in them with increasing demand for social justice. The judiciary is expected to be more sensitive to public interest and social accountability. The press, often being seen as the mirror of the society, has a constructive role to play in ventilating pressing issues, albeit including judicial functioning, to the public domain. Since judges are in positions of power to provide justice, pressure for accountability has increasingly been brought to bear on them. In exercising its constitutional power on behalf of the people, the judiciary owes its accountability to the people, who are entitled to an institution in which they can be confident. And its judges must be able to defend and explain the ways in which they exercise their judicial powers. An effective balance must be achieved between the role of judges and journalists as well as between freedom of press and the administration of natural justice.

The writer is Professor of Law, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.