Law In-depth

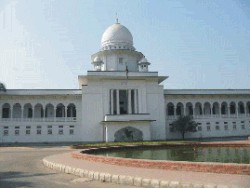

Patterns of judicial activism in Bangladesh: Constitutional cases

Kawser Ahmed

According to one U.S. scholar, the terms judicial activism and judicial activist during the 1990s appeared in 3,815 journal and law review articles, not to mention that these terms appeared in another 1,817 articles in the first four years of the 21st century -the average number of articles published per year exceeded 450 (Keenan D. Kmiec, 1994). Despite such popularity, judicial activism has remained little more than a blurred buzzword. The term has been used by many authors on the assumption that the readers will understand what they have intended to mean. In fact, judges, lawyers, scholars, journalists, laypersons everyone has his own conception of judicial activism. Even in the realm of law, the professionals and the academics are at a great deal of variances with the idea of judicial activism. Anyone would hardly resist the temptation to revisit the writings of Edward McWhinney, Justice P. N. Bhagwati and Ronald Dworkin so as to show how differently judicial activism was conceptualized by different authors having different backgrounds in different period of time.

According to one U.S. scholar, the terms judicial activism and judicial activist during the 1990s appeared in 3,815 journal and law review articles, not to mention that these terms appeared in another 1,817 articles in the first four years of the 21st century -the average number of articles published per year exceeded 450 (Keenan D. Kmiec, 1994). Despite such popularity, judicial activism has remained little more than a blurred buzzword. The term has been used by many authors on the assumption that the readers will understand what they have intended to mean. In fact, judges, lawyers, scholars, journalists, laypersons everyone has his own conception of judicial activism. Even in the realm of law, the professionals and the academics are at a great deal of variances with the idea of judicial activism. Anyone would hardly resist the temptation to revisit the writings of Edward McWhinney, Justice P. N. Bhagwati and Ronald Dworkin so as to show how differently judicial activism was conceptualized by different authors having different backgrounds in different period of time.

Edward McWhinney is the author who first attempted to make a scholarly exposition of judicial activism in two of his articles [39 MINN. L. REV. 837 (1955) & 33 N.Y.U. L. REV. 775 (1958)] during the 1950s. In his first article, McWhinney discussed judicial activism and judicial restraint respectively in terms of 'presumption of constitutionality' and 'presumption of unconstitutionality' of legislation pointing to the philosophical differences among the then justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. In his subsequent article, McWhinney recognised usefulness of activism-restraint dichotomy for clarifying thinking about judicial thought-ways. He thought that a wise constitutional judge should be able to apply the advantages of both restraint and activism; the judge needs to know when to favour which one. McWhinney conceptualised activism as a judicial tool/technique. Compared to Edward McWhinney, Ronald Dworkin offers a broader and more objective view of judicial activism. Dworkin's view of judicial activism registers acceptance of vague constitutional provisions in the spirit implying that citizens do have certain moral rights against state. Justice Bhagwati's conception of judicial activism is more functional rather than conceptual. Judicial function, according to him, inevitably behoves a judge to wear the activist's mantle [18 Commw. L. Bull. 1244 (1992)]. Adducing Plato and Aristotle's view of administration of justice, he holds that law alone is not enough for rendering justice because of the gap that exists between generalities of law and the specifics of life. This gap needs to be constantly filled up by the judges. The application of law has to be associated with and complemented by the human faculty of wisdom. He has defended judicial activism as an integral attribute of judicial function. Judicial function, according to justice Bhagwati, is essentially a goal-oriented task wherein judicial activism is rather an 'ought' than a contingency.

In the light of the foregoing discussion, this article takes the view that judicial activism signifies the approach that approves justifiable (I do not say 'justified') transgression of the limit and extent of judicial authority by the judges in order to recognize and enforce citizens' rights against state. There are two important desiderata of such activist decision making process. First, the judges have to provide justification in support of such decisions. Justification, when appropriate, has the potential to contribute towards development of jurisprudence and expansion of jurisdiction. Furthermore, justification is necessary at least for separation of powers reason. Second, any activist decision should not fly in the face of other sound principles of law and justice. The issue to be dealt with hereafter in this article is to outline (on the basis of the idea of judicial activism mentioned above) the patterns of exercise of judicial authority partaking of activism in the constitutional cases decided by the supreme judiciary of Bangladesh. It deserves to bear in mind that availability of judicial remedy generally depends on the combination of three aspects. First, there should be a violation of a substitutive legal right or breach of a duty giving rise to a legal dispute, or commission of a punishable wrong; second, the right to institute legal proceedings (locus standi) in respect of such violation, breach or commission; and lastly, the right to judicial remedies to be dispensed by the judiciary in accordance with law. The delineation of the patterns of judicial activism in the Bangladesh with regard to constitutional cases will require determining the extent and limit of the judicial authority vested in the supreme judiciary under the constitution in respect of all these aspects.

This is a two part story and check September 24 th issue for the concluding part.

The writer is an Advocate of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh.

In his message for the International Day of Democracy 2011, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said "On this International Day of Democracy, let us redouble our efforts to support all people, in particular the young the drivers of this year's momentous events in making democracy a working reality. This Day belongs to them. Let us honour their commitment to a lifelong journey in democracy. "

Democracy is a universal value based on the freely expressed will of people to determine their own political, economic, social and cultural systems and their full participation in all aspects of their lives.

While democracies share common features, there is no single model of democracy. Activities carried out by the United Nations in support of efforts of Governments to promote and consolidate democracy are undertaken in accordance with the UN Charter, and only at the specific request of the Member States concerned.

The UN General Assembly, in resolution A/62/7 (2007) encouraged Governments to strengthen national programmes devoted to the promotion and consolidation of democracy, and also decided that 15 September of each year should be observed as the International Day of Democracy.

In addition, the Assembly reaffirmed that democracy is “a universal value based on the freely-expressed will of people to determine their own political, economic, social and cultural systems, and their full participation in all aspects of life.”

The theme of the 2011 International Day of Democracy is What do citizens expect from their parliament?. Worldwide, it appears that parliamentarians are struggling to meet the ever growing expectations of citizens. Data suggests that citizens hold parliamentarians to account principally for the services that they are able to deliver outside parliament, not for their law-making role or their ability to oversee the Executive.

Source: UN.ORG.