Rights Investigation

Paradox in defining child

Survey report says "less than 1% respondents had no clear

idea about who is a child"

Children are born with rights and are entitled to protection. Creating a safe and enabling environment is a precondition in order for them to reach their full potential. However, many children in Bangladesh are at risk working or living in the street endangering their development. Others, less visible to the public see their rights violated under different forms.

Within this context, the National Human Rights Commission of Bangladesh (NHRC) held a workshop on the rights of the child on March 1st within the framework of a national campaign aiming at raising awareness about human rights and engaging key stakeholders (District administration members, members of the judiciary, law enforcement officials, journalists and NGOs) to reflect on their role in promoting, protecting and ensuring respect of the rights of the most vulnerables.

But how do Bangladeshi people understand child rights? Conducted on behalf of the NHRC, a recent survey sought to establish the baseline level of public perceptions, attitudes and understanding of human rights, including people's understanding of child rights and child labour as a rights issue. The following is an abridged version of the survey report.

Child Rights

A significant obstacle in discussing child rights is a lack of understanding about who is a child. Less than 1% of survey respondents believed people are children until age 18. This is in sharp contradiction to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which asserts that anyone under 18 is a child. Approximately half the respondents believed both boys and girls stop being children between the ages of 6 and 10, while 16-17% considered them no longer children by age five.

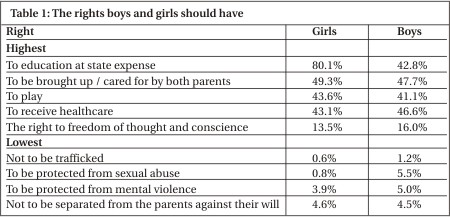

Respondents were asked which rights they believed should be protected and prioritised for children, as illustrated in Table 1:

These responses indicated people are very aware of parental and state responsibilities to raise children, but have an extremely low level of recognition of children's rights to be free from violence and trafficking and to protection from abuse, including by their families.

The right to education at state expense was much more strongly supported for boys. The survey found people are more likely to invest in a boy child's education, and to educate them to University level or their desired level, as seen in Table 2.

Regarding attitudes towards permissible violence against children, respondents generally believed verbal discipline was most appropriate for a minor fault by a child, but would accept slapping and beating with a cane for major faults. It was also widely accepted that teachers could physically discipline children for disobedience or naughtiness.

Close to 50% of women in Bangladesh marry before they turn 18, yet 93.9% of respondents did not believe this practice is right. This response is encouraging, as underage marriage can negatively impact upon girls' human rights for their entire lives. Health problems were recognised as a major consequence of underage marriage by 75% of respondents, and over 50% acknowledged that married underage girls will become mothers before they are ready. Respondents most commonly believed the practice continues due to poverty.

Child Labour

One major barrier to the realisation of children's rights in Bangladesh, and especially the right to a childhood protected from violence, abuse and exploitation, is child labour.

Child labour, as defined by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), is work that exceeds a minimum number of hours, depending on the age of the child and on the type of work. It can expose children to a multitude of risks including injury and death, health problems, sexual exploitation and violence. As a signatory to the CRC, Bangladesh is obliged to protect children from economic exploitation and from work that is hazardous or interferes with their development.

Bangladesh has ratified the Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour, but has yet to do so for the Convention concerning Minimum Age for Admission to Employment. While there is no uniform minimum age for admission to work in Bangladesh, the Labour Act (2006) prohibits employment of children under 14, and hazardous labour for anyone under 18.

Encouragingly, the Ministry of Labour and Employment recently adopted a National Child Labour Elimination Policy (2010), providing a framework to eliminate all forms of child labour by 2015. However, with 93% of working children employed informally, the Labour Act is minimally enforceable and eliminating child labour will be a huge task.

The survey showed high levels of awareness that child labour can be harmful, acknowledged by 91.5%, and relatively high awareness that law and policy exist to regulate it, with 41.6% aware of some law or policy. Ninety per cent of respondents said children aged 5-11 should not do any paid work. In contrast, most respondents said children aged 12-17 should be allowed to do paid work, but were more accepting of boys in this age group working, as only 37.7% would not allow boys to engage in paid work, compared to 49.5% who would not allow girls. Despite high levels of understanding about the negative impacts of child labour, poverty leads some parents to see little option but to allow their children to work.

It is widely accepted that education is an essential measure in poverty alleviation. Sadly, of children aged 5-14 in Bangladesh, approximately 13.4% (or 4.7 million) work, and 7.3% work and do not attend school, with rural working children less likely to attend school than urban working children. UNICEF recently reported that approximately half of all child labourers do not attend school at all, and only 11% of child domestic labourers (the most common form of child labour) attend school. Thus, while child labour is perceived as a way out of poverty, working children who do not receive an education can become stuck in a lifetime of low-paying, low-skilled jobs, thereby perpetuating the cycle of poverty, rather than lifting families out of it.

Recommendations from the report authors include:

-Including a definition of who is a child in all child rights campaigns, to improve understanding of the universal definition.

-Raising awareness on child rights, especially to be free from violence and trafficking and to be protected from abuse, and that girls have an equal right to education

-Tapping into existing awareness of health issues to advocate for an end to underage marriage.

-Undertaking a concerted public education and awareness campaign on the consequences of child labour. NHRC should consider partnering with UNICEF, given the work they already do in regards to child labour and trafficking.

-NHRC should lobby for changes to the Children Act (1974) to bring it in line with the CRC.

Source: National Human Right Commission.