textile timelines…

khadi and the guho family

IN

1921-22 Mahatma Gandhi and his followers were on a mission for peace

and patriotism. Their approach was simple, as was their choice of

attire. They embraced the rough textures of the spun cotton material

known as khadi.

In

our country Shoilen Guho is considered as the pioneer of the khadi

creations and was known as Khadibabu. During his school days

in Chittagong he took a deep interest in the creation of this material.

The carpus cotton of Rangamati was spun into fibre for all

kinds of ropes, strings and fishing nets. At that time one of the

landlord's sons came back from abroad and set up a weaving factory.

Shoilen Guho learnt the rest of his trade at the factory.

In

our country Shoilen Guho is considered as the pioneer of the khadi

creations and was known as Khadibabu. During his school days

in Chittagong he took a deep interest in the creation of this material.

The carpus cotton of Rangamati was spun into fibre for all

kinds of ropes, strings and fishing nets. At that time one of the

landlord's sons came back from abroad and set up a weaving factory.

Shoilen Guho learnt the rest of his trade at the factory.

The

cotton needed to be soaked overnight and later would be treated with

starch before being put on the loom. Around 1931, during his teen

years, khadi was a very popular material. Shoilen was so

into the craft that he used to gather the thread from surrounding

villages and spin and sell his own cloth. At the same time he used

to work at the Chittagong National Textile Mill as the dyeing master.

What he learnt there regarding the coloring of cloth served as an

invaluable experience later on.

Abhoy

Asram in Chandinath, Comilla was a centre for spinning yarn. Warda

cotton was used for this purpose, resulting in a much better product.

Shoilen spent a lot of time there to create and promote khadi

as well as to educate and train the locals in the art of spinning.

His business expanded, as there was a boom in the demand, and he started

supplying his products to Calcutta. It reached a high with a conference

featuring the textile, which was directed by Shoilen.

Despite

the popularity, the hand-cut material could not catch on in the market

at the time. Shoilen died in 1995 continuing his undying love for

the simple clothing material. He implored everyone to at least purchase

one sari, panjabi or dhuti made of khadi every year. He felt that

it was necessary to protect the heritage.

Despite

the popularity, the hand-cut material could not catch on in the market

at the time. Shoilen died in 1995 continuing his undying love for

the simple clothing material. He implored everyone to at least purchase

one sari, panjabi or dhuti made of khadi every year. He felt that

it was necessary to protect the heritage.

Shoilen had three

sons and two daughters. The elder sons worked with the father while

Arun, the youngest, studied mechanical engineering in Calcutta. His

first work experience took place in Kumudini related to dyeing and

block printing. He worked with his father later on to supply materials

when Aarong was established. Some time before and after Shoilen's

death famed fashion designer Bibi Russel had a hand in promoting khadi.

With her help and Shoilen's creative usage of colours and quality

control, the rural clothing item has achieved international recognition.

At the same time it has provided employment for countless artisans.

Rebirth

In the 50's khadi had risen high in the Indian market due to intense

promotion. The quality improved greatly with government aid and a

lot of effort on the personal level. Comparatively that did not seem

to happen in our country. Shoilen and his fellow craftsmen produced

enough to meet the market demand but khadi could not take over the

market from the other cloths although it came to a lot of uses and

was inexpensive.

The

following years of the Liberation War saw a rise in patriotic feelings.

Joblessness brought about many entrepreneurs and some of them started

promoting home made clothing with the aid of khadi. Ashraful Rahman

Faruq was one such youth who presented khadi as a fashionable ensemble.

He opened the first shop catering khadi goods at Malibagh in Dhaka.

The outlet was called Nipun and there was everything on offer from

blankets and napkins to panjabis and shawls. He did not rest at simply

creating the clothing materials but went further to add value by utilising

colouring, printing and block techniques. Thus, other shops displaying

khadi sprouted such as Champak, Kumudini, Joya etc. It was the birth

of a new country and what better way to join the jubilation than to

revel in the country's own product? With such a mindset, K S M Faruq

opened up Khadi Bitan near the Dhaka Science Laboratory, selling khadi

from Comilla.

The

following years of the Liberation War saw a rise in patriotic feelings.

Joblessness brought about many entrepreneurs and some of them started

promoting home made clothing with the aid of khadi. Ashraful Rahman

Faruq was one such youth who presented khadi as a fashionable ensemble.

He opened the first shop catering khadi goods at Malibagh in Dhaka.

The outlet was called Nipun and there was everything on offer from

blankets and napkins to panjabis and shawls. He did not rest at simply

creating the clothing materials but went further to add value by utilising

colouring, printing and block techniques. Thus, other shops displaying

khadi sprouted such as Champak, Kumudini, Joya etc. It was the birth

of a new country and what better way to join the jubilation than to

revel in the country's own product? With such a mindset, K S M Faruq

opened up Khadi Bitan near the Dhaka Science Laboratory, selling khadi

from Comilla.

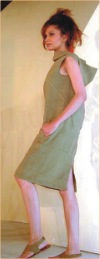

The 80's saw a

revolution in the demand for khadi. Men could find everything from

winter jackets and scarves to summer outfits like panjabi. Aarong,

Kumudini and later Prabartana promoted khadi in a different light

as something desirable. They had their own designers along with their

own factories and craftsmen.

Prabartana has

been able to increase the demand for khadi with its unique offerings

throughout the past decade. They have used their own personnel, production

techniques and expertise to make khadi into a comfortable cotton fabric

fit for regular use.

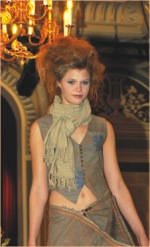

Bibi

Russel and khadi

Bibi

Russel and khadi

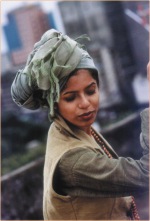

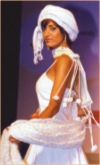

Internationally famed designer and model Bibi Russel came back to

Bangladesh in 1994 and started work on developing the local weaving

industry. She set her sights on the jamdani, muslin, check and khadi

centring the materials for a fashion development program. A lot of

the work revolved around Shoilen Guho's khadi products. The duo helped

to bring khadi further into the limelight during the mid-nineties.

Bibi arranged fashion show at home and abroad to increase the popularity

of khadi resulting in a significant following alongside Indian khadi.

Bibi commented

that people prefer to use natural and ecologically friendly materials

like khadi. She is endeavouring to further the work that Shoilen Guho

started and also trying to protect the Comilla khadi society. She

also said that nowadays, real khadi, whose threads used to be a little

thicker, is no longer prepared. It had its own elegance. At present

khadi is made with mixed fibres.

She also informed

that the fashion shows have been organised to promote khadi and these

will help the artisans. Unfortunately, this year the flooding has

almost brought the industry to a standstill. The financial hardships

have to be overcome by providing extra orders for the weavers.

The

challenges

The

challenges

In the words of Gandhi, khadi is a fabric for human values and ethics.

It delivers the people from the bond of the rich and creates a spiritual

bond between the classes and the masses.

The creation of

khadi follows a certain rhythm for which even an old woman who cannot

see can sit and spin out the thread with utmost skill. A weaver can

use that thread to churn out 8-12 yards of material. In return they

get a stipend of 12 taka per yard. In cases where there are two designs

on one cloth then they pay charges accordingly. Most of the khadi

in the country is made from waste cotton. Now, the word 'waste' may

sound bad, but in reality it isn't. It's more of recycling. You see,

the textile mills discard a lot of cotton and this is used in turn

to spin a thick thread.

Khadi has a lot

of potential. In the past two years there has been a dramatic rise

in the demand with a wide range of clothing for both men and women

available in this material. The many different designers and boutiques

are in a race to create the most desirable ensemble. The thick khadi

thread is used to create different patterns incorporating modified

weaving techniques.

Those

who are involved with khadi are also facing many difficulties. Arun

Guho, the country's primary khadi producer, explained that proper

cash inflow is needed to keep the industry on a winning streak. Many

times items are delivered on credit. Also the cotton required for

production is often unavailable according to demand. As a result the

workers have to make do with whatever is available. A continuous twelve-month

work period cannot be maintained. Thread made with pit loom and power

loom does not provide a good finish. Producers of khadi spend about

eight months using thread from textile mills and the other four months

using cotton threads. Despite the fact that some other producers are

doing well using foreign yarn Arun Guho wants to stick to using local

material.

Those

who are involved with khadi are also facing many difficulties. Arun

Guho, the country's primary khadi producer, explained that proper

cash inflow is needed to keep the industry on a winning streak. Many

times items are delivered on credit. Also the cotton required for

production is often unavailable according to demand. As a result the

workers have to make do with whatever is available. A continuous twelve-month

work period cannot be maintained. Thread made with pit loom and power

loom does not provide a good finish. Producers of khadi spend about

eight months using thread from textile mills and the other four months

using cotton threads. Despite the fact that some other producers are

doing well using foreign yarn Arun Guho wants to stick to using local

material.

Shamim

Hossain, director of Prabartana, informed that the greater demand

of khadi comes from the middle class. Sales are good but not as much

as expected. One of the reasons is that good quality cotton is not

easily available. Without good cotton the weavers lose interest in

the work. Also there is the ongoing system of middlemen that just

exacerbates the condition.

Shamim

Hossain, director of Prabartana, informed that the greater demand

of khadi comes from the middle class. Sales are good but not as much

as expected. One of the reasons is that good quality cotton is not

easily available. Without good cotton the weavers lose interest in

the work. Also there is the ongoing system of middlemen that just

exacerbates the condition.

Khadi's acceptance

among the new generation is increasing. It is used not only for clothing

materials but also as part of home furnishing in the form of curtains,

bed sheets etc. Khadi is an old tradition and it only goes to show

that old is indeed gold.

By

Sultana Yasmin

Translated by Ehsanur Raza Ronny

Special thanks to Bibi Russel, Bibi Productions and

Shamim Hossain, Probartana, Model on the cover: Faika