My

mother used to say I started to hum much before I

started to talk,” Ferdausi Rahman, one of the finest

artistes of Bangla music, speaks of her initiation

into music. Being the only daughter of legendary Abbasuddin

Ahmed, the king of Bangla folk songs, music was very

much in her blood. Her first lessons in music began

under the tutelage of her father. “My father would

take not only me, but all three of us (Ferdausi and

her two elder brothers, Mostafa Kamal Abbasi and Mostafa

Zaman Abbasi) together and make us sing with him.

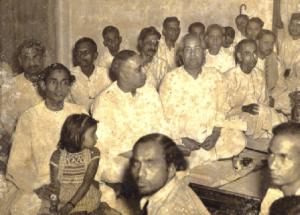

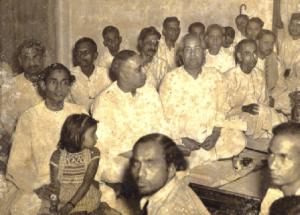

Child Ferdausi

with her father at a literary gathering.

Sometimes

I used to accompany my father to different places

to sing with him. Sometimes, however, he would leave

me alone on the stage and make me sing,” she remembers.

Ferdausi took lessons in classical music from several

renowned Ustads like Muhammad Hussain Khosru, Yusuf

Khan Uuraishi, Qader Zamiri, Nazakat Ali Khan and

Salamat Ali Khan.

Ferdausi went on air when she was only six. She became

a regular artist of the television when Dhaka Television

started in 1964. In fact, she happens to be the first

artist of Dhaka Television. Even before that, Ferdausi

had already begun to sing in the films for both Bangla

and Urdu films. Till date, she has sung for about

200 films. Since her childhood Ferdausi has traversed

a wide range of music with equal ease and skill. Her

strong foundation in classical music enables her to

make the different genres of music sound as if each

was her specialisation. While the more classical based

music like Khayal, Thumri, Ghazals are her forte she

is also the exponent of traditional Bangla music like

Bhawaiya, Bhatiali, Folk songs. She has also made

her mark in Nazrul Geeti, and modern songs.

Ferdausi with

her numerous awards in 1954.

It was sometimes around the late sixties. Ferdausy

received a rather strange proposal. “Montu bhai (artist

Mostafa Monwar) who was our family friend, wanted

to involve me in a children's programme. I refused

point blank, but finally gave in to his relentless

persuasion,” Ferdausi recalls how this particular

programme started. It was, 'Esho Gan Shikhi', a programme

that offered music lessons to children on television.

Ferdausi's unique handling of the programme, specially

her ability to interact with children with a little

bit of pep talk and that well-known, ever-assuring

smile, gave the programme a different kind of charm

and liveliness. Then there was Mithu-Monti, the puppet

duo, who engaged in mutual fighting at every opportunity

and sang out in their strange voice, often distorting

the melodious chorus. “Children keep on asking me

about MithuMonti. Khalamoni, why can't we see their

feet? Why don't they go near your dais and give music

exams?” Rahman says.

Ferdausi Rahman

performing on the BBC, November 1967.

In the late seventies a new chapter opened up in her

illustrious career. Already a veteran of more than

a hundred films as a playback singer, Rahman ventured

into music direction. Not willingly though.

“I never thought of composing music until I was kind

of forced into trying my hands in music direction.”

It was the renowned filmmaker Ehtesham, who asked

Ferdausi to do music direction in his film.( She used

to call him chacha and he also fondly called her chacha).

A somewhat bewildered Ferdausi rejected the idea:

“What do I know of music direction?” Finally, however,

she agreed to give it a try. Along with Robin Ghosh,

who would later become the famous music director,

Ferdausi gave music direction in Rajdhanir Buke. The

film was a hit, so was its music. One of the songs

of this film has found a place in the all time greatest

hits of Bangla film songs: Tomare legeche eto je bhalo,

chand bhujhi ta jane..ee… ee, ratero basore doshor

hoye tai she amare tane……... Hardly a week went by

before film lovers in Dhaka and soon the entire country

was humming this song. And the song is just as popular

today.

The artiste

with legendary Ghazal singer Mehdi Hassan.

A

confidant Rahman then accepted another film Megher

Onek Rong. This time she did the score all by herself.

Interestingly there were no songs, so Ahmed had to

play around the background music. “It was extremely

challenging and I worked really hard for that film,”

she recalls. Her efforts didn't go unrecognised. The

film won the National Award for Ferdausi in the category

of music direction. Ferdausi then gave music direction

in two more films -- Nolok and Garial Bhai. The movie

Garial Bhai however couldn't be completed for some

reason even though the music was done.

Unfortunately Ferdausi's career as a music director

was destined to be short-lived. It was the early eighties

and the copying spree that would engulf the Bangla

filmdom had already started to surface. Thus, in spite

of the huge success of her composition, that too,

with only three films to her credit, Ferdausi had

to impose self-retirement. “Besides less and less

number of people were coming to me, as they knew that

the kind of music they need for their films would

not be done by me”, Ferdausi remembers. The copying

has now grown so rampant that people have even stopped

complaining about it.

Bangla music has long lost its glorious days. What

we have today in the name of Bangla music has very

little Bangali element in it. The rich mellifluous

tune of our Bangla music, very much characteristic

of the soil it springs from, is not heard anymore.

Ferdausi feels sad, sometimes regrets, but never loses

heart at the wretched state of Bangla music. She points

out some of the main reasons behind that. Our absolute

indifference to or ignorance about our traditional

Bangla music has left us musically rootless. Secondly,

the ever-spreading virus of copying has gradually

infected the entire Bangla filmdom and with it, its

music. The advent of satellite channels have also

brought about radical changes in our musical taste,

particularly among the younger generation. “I am not

against Hindi songs, but that should not be at the

expense of our own musical heritage,” she says.

Ferdausi Rahman

with her husband.

But who is responsible for this wretched state of

our films and film music? Is it the bad taste of those

who make films or those who watch and enjoy them?

Ferdausi uses an analogy to answer: “It is the responsibility

of the housewife to serve good food. If she keeps

on serving bad, stale and adulterated food, others

in the house will begin to like it. Simply because

they haven't tasted good food.” She believes that

'making money' has become the guiding principle and

'greed' the basic 'driving force' among most of them

who invest money for filmmaking. No doubt filmmaking

has its commercial/business side, but a film is also

an art work, she argues. “And as far as business is

concerned, good films do make profit. There are numerous

examples”, she says.

Ferdausi is also critical about television's performances

when it comes to upholding and promoting our cultural

heritage of which music is a most vital component.

Again, since BTV or Betar for that matter, is not

supposed to be worried about making profit, they are

in an ideal position to promote and nurture our musical

heritage. The picture is unfortunately exactly the

opposite. Those who are in charge of running the television

are more concerned about their own 'chairs' and busy

in exploiting their official positions to pursue their

personal interests. They care little about how a programme

should be improved or what new things can be added

or doing experiments or playing with new ideas.

Besides, some musical programmes like those of classical

music and folk songs are presented with great negligence,

Rahman alleges. While these programmes receive lowest

attention in terms of time slot, budgetary allocation,

recording facilities, etc. The way those programmes

are presented (bears no marks) of even the most minimal

of effort and thought that usually go into making

a good programme. Naturally such dull and boring productions

don't interest the audience who, instead, grow a permanent

distaste to traditional folk music. Whereas, the copied

film songs and other musical programmes enjoying great

care and often luxurious treatment.

Besides, what is the cultural ministry doing? She

asks, it is the job of the cultural ministry to nurture

our traditional Bangla music. They haven't even managed

to preserve what we have, not to mention nurturing

it, she accuses.

The private television channels have also done precious

little in this regard, Rahman alleges. Our treasure

of musical heritage continued to be neglected. Besides,

standards are often compromised for commercial concerns.

“You want to make quality programmes, but when it

comes to paying the artists you become close-fisted,”

Rahman doesn't hide her disapproval of such bad tendency.

Again, petty political considerations and sectarian

interests have often done serious harms by creating

divisions and mistrust in artist community. Rahman

doesn't mask her resentment as she talks about the

'black listing culture' of artists mainly in the government

controlled media. Every time a government is changed,

a blacklist is prepared of some artists who allegedly

enjoyed the previous government's blessing. After

5 years the same procedure is repeated. This must

be stopped…,' she goes on, 'I am sorry but I must

say that this practice had its origin in '71. Some

artists who stayed in Bangladesh during the war and

did programmes on TV or Radio were readily labelled

as “collaborators”. They did not try to understand

the circumstances--in many cases artists were forced,

even at gun-points to do programmes. But nobody seemed

to be listening', she pauses after a long gap.

In a career spanning over almost five decades Ferdausi

Rahman has received many awards in recognition to

her achievements and contribution to the different

branches of Bangla music. The President's Pride of

Performance Medal in 1965, Ekushey Padak, Shadhinota

Padak, Best TV Singer National Award, Pakistan Film

Journalists Award are only the more illustrious entries

of a surprisingly long list.

At present Ferdausi is busy with Abbasudin Music Academy.

She hopes to acquaint today's children with their

rich musical heritage, which, seems to be fast vanishing.

She has a dream. “I want to send my students to every

locality, where they will teach the people one or

two particular songs. Gradually the entire country

will learn to sing a common song. Wherever you go,

whoever you are with, the moment you start to sing

that song everybody around you joins you immediately.

Isn't it great?” she asks eagerly. Yes, it is.