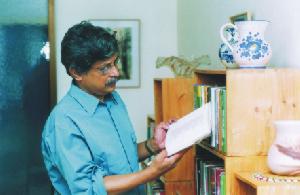

As

the Piper of Hamlin cast a spell on the children and

made them follow him with the music of his pipe, Muhammed

Zafar Iqbal has kept childrn enchanted with the magic

of his pen. He has not only filled in the vaccum of

writers in the field of children's literature he also

deserves kudos for successfully bearing the legacy

of this extremely rich treasure of Bangla literature.

He is prolific, powerful, imaginative yet combined

with a pragmatism that appeals to the younger generation.

He is one of the finest happenings in modern Bangla

literature.

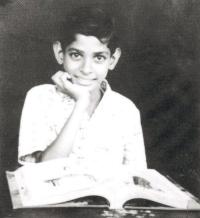

He

is not sure exactly when he started to write. Writing

came too naturally for him to remember the precise

timing. Iqbal attributes this knack for writing to

his family environment, where 'reading' was very much

a part of life and 'writing', a passion every member

of the family shared. "In our house all of my

brothers (his elder brother Humayun Ahmed and younger

brother Ahsan Habib would become reputed writers)

and sister used to write, so 'I can write' was hardly

a revelation to me," Iqbal explains.

“We, brothers and sister, took to reading since our

early childhood. Our house was full of books, in fact,

the collection was, 'disproportionately larger', for

a middle class family as ours. When a new book arrived,

a fierce competition would ensue among us to read

it first. There were many books at home which all

of us including my father and mother had read and

enjoyed," Iqbal reminisces.

However, it was his father who had exerted the greatest

influence on him as well as his brothers and sister.

To such an extent did the influence work that they

discreetly vowed that when they would grow up they

would smoke, because they just loved to watch their

father smoking, “particularly the way he elevated

the task of smoke to an artistic level”. Humayun realised

the vow quite early and the younger ones also picked

it up in time.

A police officer by profession, his father was a great

connoisseur of literature and an avid reader. And,

it might take many by surprise, he was also an enthusiastic

writer. He used to write short stories, travelogue,

essays etc and in fact had a few books published.

During the liberation war when their house was looted

most of his manuscripts got lost. He spent most of

his spare time reading or writing, and sometimes reading

to the children who would sit encircling him. "One

of my fondest childhood memories is that of my father

reading to an eager battalion of audience comprised

of all of my brothers and sister," Iqbal recollects.

So did their mother. Iqbal's memory of those great

moments when his mother used to read to him from Thakurmar

Jhuli is still fresh and so are the effects they caused.

Young Iqbal's imagination would be greatly stimulated

by those fairytales; he would lose sleep at the ill-fortune

of the prince who had been transformed into stone;

his afternoons became gloomy for the princes who had

been kidnapped and imprisoned in the patalpuri by

the one-eyed wicked rakkhosh; and in his dream he

would undertake deadly missions to rescue the princes

from the prison. No doubt, Iqbal had his lessons to

fly on the wings of imagination in his early childhood.

Meanwhile

Iqbal was writing off and on, more often just for

the fun of it and only occasionally in school magazines

and other amateur publications. Iqbal was at Dhaka

University doing Honours in Physics, when his first

story got published in the now-defunct but once the

most influential Bangla weekly magazine “Bichitra”.

But even before he could savour his achievement, one

of his acquaintances accused him of plagiarism. The

young writer's pride was greatly offended, but he

didn't know what to do to disprove the allegation.

“I thought the best way to prove my innocence was

to show more evidence that I could write,” and so

he started to write with mighty speed. Within a very

short time some half-a-dozen new stories were born,

and published under one cover. It was Iqbal's first

book, Copotronic Sukh Dukkhu. The book was a hit.

The

success of his first book not only healed his wounded

pride but, more significantly, it gave the aspiring

young writer great confidence in his ability. He now

sent Haat Kata Robin to the publishers, a novel, which

he actually wrote even before Copotronic Sukh. Very

soon his second book hit the market and fared even

better. Before he left for America for higher studies

Iqbal got another of his book published. It was 1976

when Iqbal went to the University of Washington on

a scholarship to do PhD. He then went to Caltech University

to do post Doctoral. Around 1989 he joined Bell Communications

Centre as a Research Scientist where he worked on

fibre optics.

He,

of course, never stopped writing. Though he had little

time after enduring long hours in classrooms and longer

hours in the laboratory, he always had time for writing.

Writing for him was the greatest refuge to escape

from homesickness. The very process of writing gave

him the opportunity to recreate the scenes and sound

of the homeland; thus enabling him to enjoy the familiar

fragrance of the soil, birds flying away along the

familiar skyline, rains creating that great familiar

symphony and all those simple pleasures of life he

had been sorely missing living abroad. But from time

to time he used to have a vague feeling, as if something

was missing somewhere. Perhaps he was suffering from

a lack of motivation, as he couldn't have the first

hand knowledge of exactly how his books were faring.

Suddenly something significant happened.

It was around 1988. He met writer Jahanara Imam, who

was on a visit in America. He introduced himself as

the younger brother of Humayun Ahmed, but to his great

surprise, she told she knew him very well. She also

mentioned she liked his writing very much and went

out of her way to find his books and read them. "I

was overwhelmed by such compliments from someone of

her stature," Iqbal recounts. He felt extremely

inspired, the way he never felt before. And suddenly

the mystery of his vague feelings was solved. What

he was missing was 'inspiration' or 'the feedback

of the readers', which Jahanara Imam had just showered

on him, unknowingly though. He now started to write

with renewed enthusiasm and by the time he came back

he had written 27 books.

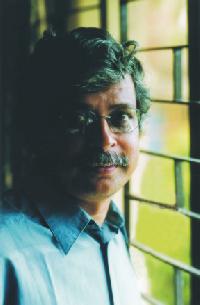

In

1995, Iqbal finally decided to put an end to his expatriate

life, after 18 years. He joined Shahajalal Science

and Technology University in Sylhet as a professor.

At present he is the Chairman of the Computer Science

and Engineering department.

"But why did you come back?"

During the last eight years since his homecoming he

has again and again had to face this, what he feels,

a rather unsavoury query, from relatives, well-meaning

friends and interviewers alike. That he doesn't see

reason in such a question is obvious in the way he

answers it: "You ought to instead ask why I didn't

return after five years, the time I took to accomplish

my goal (obtaining PhD)." One reason for his

belated return is, he wanted 'to save some money'

before coming back. "But somehow my progress

remained disappointing on that account," Iqbal

recollects.

But

what was it that was drawing Iqbal to his motherland

with such an irresistible force. Was it 'patriotism'?

Iqbal laughs. "It was just that I used to miss

Bangladesh badly. I heaved a sigh of relief when I

came back. It was as if I was again breathing freely,"

he tries to explain why he came back. There were other

reasons too which, through worldly eyes might seem

worthless, but with Iqbal's romantic temperament they

were invaluable -- rains and frog's croak. "Every

time it rains I cannot help thanking God for I am

here, in Bangladesh," Iqbal says.

And, of course, he never regretted his decision. Not

even when bombs were being hurled on my house and

I had to buy tickets for my family members using fictitious

names so that they could board the plane safely,”

he says in one breath. Iqbal refers to the brawl centring

around the naming of residential halls in the university,

where he was targeted for not complying with the illegal

demands of Jamaate Islami and other like-minded communal

forces.

Back home Iqbal discovers that he enjoys quite a sizeable

readership. In a couple of years' time Zafar Iqbal's

books were in the short-list of best sellers in the

Ekushey Boi Mela. He kept writing on…

Zafar Iqbal has established himself as one of the

major writers of contemporary Bangla literature. What

earned him the position? His greatest achievement

is that he has almost single-handedly borne the legacy

of that extremely rich genre of Bangla literature,

which we call 'children's literature'. This particular

stream in Bangla fiction had had the service of great

craftsmen like Dakkhinaranjan Mitra and Sukumar Roy

with Thakurmar Jhuli and Abol Tabol or

Hojoborolo marking the highest point of that

genre. A decade on another master arrived on the scene,

Satyajit Roy, the internationally acclaimed Oscar

winning filmmaker and an exponent in this genre, pushed

the limit of children's literature still further by

his detective (Feluda) stories. In comparison the

last two decades or so has experienced sort of a lean

period, at least when it comes to champions of that

stature just mentioned. There have been, to be sure,

some powerful, creative practitioners of this form

of literature, who might not have surpassed their

predecessors but certainly have carried along the

legacy of one of our richest treasures of Bangla literature.

Muhammed Zafar Iqbal certainly leads the pack. Surely,

Iqbal has written for adults, but his recognition

and fame rest on his works for children. (Out of some

84 more than 60 books are for children).

Why

does he write for children? Iqbal believes it has

a lot to do with his own childhood. “Children are

naturally very sensitive and impressionable. Every

great book I read then had left a permanent impression

in my mind. An intense feeling of pleasure remained

in the heart for a long time after I finished a book.

When I started to write I remembered those feelings

of great pleasure and thought what greater achievement

a writer can aspire for than invoking those feelings

in a child as I had experienced in my childhood?”

Iqbal explains. It's very challenging and if popularity

can be considered a criterion, Zafar Iqbal certainly

has that the gift to handle that challenge very well.

It is almost impossible to read his children's fiction

and not wonder how a middle-aged man understands how

a child thinks and feels. The way he depicts the child

characters and their peculiar way of thinking, manufacture

their behavioural pattern go to show his great understanding

of child psychology. Perhaps this is what Masheed

Ahmad, means when she says. 'While reading his books,

it seems the narrator is a child'. Masheed, a 4th

year student of Mechanical Engineering Department

at BUET and a long-time fan of Zafar Iqbal, doesn't

take time to think when asked why she loves his writing

-- “I can easily relate these stories to my own childhood

experience. The pranks and mischievous acts that he

described were so interesting that as kids, we wanted

to adopt similar kind of tricks to bunk studies at

home.” The animated accounts of school scenes appeared

in many of his fictions. Another Zafar fan Subrata

Saha, Assistant Manager of Basic Bank remembers from

one of his most favourite 'Amar Bandhu Rashed',

“Reading Iqbal is like revisiting my sweet school

days. The classroom environment has been portrayed

so authentically that every time I read the book it

seems, I might very well have been one of those child

characters. Those universal school-boyish practice

of giving names both to classmates and teachers, the

hate-at-first-sight for the newcomer gradually transforming

into great friendship and the general ill-feeling

among average students for the first boy of class

so truly reflect my own school days”.

Humour

is another aspect of Iqbal's writing his fans love

very much. This is one quality common to all the three

brothers, (Humayun Ahmed, Zafar himself Ahsan Habib)

“Perhaps, this is in my genes,” Iqbal observes half-seriously.

And, he hastens to add, we come from an area (Iqbal's

home district is Netrakona) where people have a great

sense of humour. Be it the regular children's fiction

or science fiction, humour abounds in Iqbal's writing.

The reader finds it hard not to break into laughter

or at least a giggle at regular intervals. The book

which is most frequently named in this connection

is Bigyani Safdar Alir Moha Moha Abiskar.

This is the story of a crazy scientist who spends

years to discover the already discovered fact that

trees have life; equips his spoons with a tiny fan

so that when he injects it into jeelapis

they get cooled immediately; gives advertisement in

the newspaper looking for a monkey whom he wants to

assist him in his research, because a human assistant

might collaborate with the FBI and CIA and help them

getting hold of his invaluable discoveries. Harun-ur-Rashid,

a lecturer at Asian University, likes this character

of Safdar Ali very much: “Life wouldn't have become

so boring if there were a Safdar Ali around”. Masheed,

another admirer of the book, wonders why he doesn't

write such fiction any more.

Another

branch of Bangla fiction Zafar Iqbal has immensely

contributed to is science fiction. He is perhaps the

first major author who has so extensively experimented

with this form and certainly the one who has popularised

science fiction among the mainstream readers.

What makes his science fiction interesting even to

those who have no knowledge of science is that he

never allows science to get the better of fiction.

His focus remains in the story and he exploits science

only just to create a certain kind of situation where

he wants to stage the original drama. One recurring

theme of his science fiction is the encounter between

the aliens and humans as well as the consequences

they affect. These encounters are imaginative manifestations

of the meeting between the present and the future

represented by the conflict between man and machine,

human values and superior intelligence. At his best

he can engage the reader and even make him feel the

tension. Though his science fiction is very popular,

some of his long-time fans feel that Iqbal is becoming

repetitive and sometimes predictable these days.

Besides

being a very popular writer Iqbal has also established

himself as a popular columnist in the last few years.

Iqbal, however, doesn't have great fondness for the

columnist title. "It seems to me that the only

task of the columnists is to find fault with everybody

and everything. They seem to be writing on everything

as if they knew everything,' he reasons. "I am

not a regular columnist. Sometimes one particular

event or another 'disturbs' me and on those occasions

I feel like sharing my views with my readers,"

he explains. At present he is writing on such a topic--

on the controversial question setting in the HSC final

where examinees were asked to write a paragraph on

Eid-ul Fitr.

At a time when newspaper columns are seen only as

another place of mud-slinging among the intellectuals

belonging to opposite camps, Zafar Iqbal is one of

the very few exceptions, who have managed to save

the chastity of his pen and has obstinately continued

to express his mind. Neither has he been cowered at

the face of continuous overt and covert assaults from

the communal might and has relentlessly espoused of

liberal thinking and secular beliefs. What distinguishes

Iqbal's columns from those of others is his courage

to say what he believes in. "Since I don't want

to be the VC, I don't have to bother who I am making

unhappy as long as I am writing the truth," he

says.

The characteristic simplicity of his language and

clarity of perception give his columns an easy motion.

Like other columnists he never burdens his columns

with overdoses of information, neither does the reader

lose track in the maze of logic and references. Instead,

he brings in personal experiences and interesting

anecdotes, which make his writing very easy and enjoyable

reading.

Since

his return Iqbal has been working for the development

of our IT (Information Technology) sector. He had

both the experience and expertise in this field and

he had before him the encouraging example of India,

where IT revolution has changed the lot of thousands,

not to mention the huge boost it has had to that country's

economy.

Unfortunately things didn't work the way it should

have been. Programmers have been created but the opportunity

to employ this workforce could not be worked out.

"The reason was our failure to create the situation

where we could develop software industrially,” Iqbal

specifies where we went wrong. The non-resident Bangladeshis

didn't do what the non-resident Indians did by 'bringing

in orders' from the big clients abroad.

“The

communication gap between the client and the producer,

that was to be bridged by the expatriate Bangladeshis,

never really gave us the chance to develop software

industrially," Iqbal points out. The two successive

governments since 1991 also did precious little. In

the first place they were late to realise that the

potential of this sector remained short and even when

it did, it continued to act in its own usual wishy

washy, visionless way.

In his 25 years writing career he never won an award.

He however doesn't have any regret for that: “It also

has its advantages, I am often invited to various

children's programme and asked to distribute prizes

among the winners. On those occasions I can console

those who haven't received any prizes, saying that

I also never have got any.” He however is always receiving

the greatest award a writer can aspire for-- love

of his readers. Everyday Iqbal receives numerous letters

from his child admirers. In their flawed sentence

structure, faulty spelling, immature hand-writing

and inarticulate expressions they send lots and lots

of love for him.