| Stories

Behind Lines

Mustafa

Zaman

"It

all began from an emotional involvement with the elderly,"

exclaims the photographer who had been interacting with

elderly people for the last two years. Tanjilur Rahman's

clarion call came right after he lost his father in December

2004. In a condolence meeting arranged right after that

many of his father's well wishers turned up and had so many

things to say, it made Tanjil realise that he, as the youngest

son of his recently deceased father, did not know him well.

"I hardly had the chance to interact with my father.

Like any other middle class family, in ours too a wide rift

between the father and the sons existed," Tanjil confesses.

His

father's condolence meeting lasted for four hours. The speakers'

words did not work a gloomy spell on him as they usually

do in these circumstances, rather he was brought to the

realisation that the elderly in our society are treated

as non-persons. Towards these non-persons Tanjil developed

an empathy that set him to record their faces. His

father's condolence meeting lasted for four hours. The speakers'

words did not work a gloomy spell on him as they usually

do in these circumstances, rather he was brought to the

realisation that the elderly in our society are treated

as non-persons. Towards these non-persons Tanjil developed

an empathy that set him to record their faces.

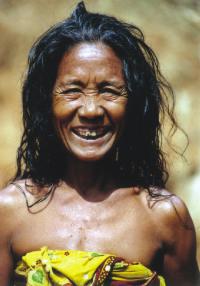

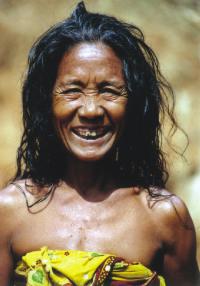

Any

face mirrors a state of mind. It also speaks of the condition

that one lives in, and does so more eloquently than words,

as is demonstrated by this twenty-plus photographer. His

photographs reveal a series of portraiture of elderly people

in whose visages signs of deprivation are embedded as if

they are weathered by it. As victims of apathy, all the

pent-up emotions is now wrapped under silence. Old age has

robbed them off the kind of emotional and physical interaction

they enjoyed. Their status as social beings has gone through

a drastic downgrading, as they reached the fag end, and

most of them are struggling to adapt to the state of inaction.

Tanjil reveals their story with a different touch.

After

interacting with these people, who in real life simply developed

into a different species of sorts, he realised that after

being forced to the margin of each household they once belonged

to, they have nothing to look forward to, no one to turn

to. "All they need is a little care from the family

members. Can you imagine that most of them simply forgot

how to laugh!" says Tanjil, whose images capture a

few intimate moments in the lives of these people.

What

Tanjil recorded are not only portraitures. He accumulated

the responses of these elderly persons, after they were

treated with respect and, most importantly, with some compassion,

of which little is being thrown in their direction. "I

spent time with them. Each man or woman I met, I spent hours,

or at times, days to make them smile," says Tanjil,

who

picked up his camera only in 2002, after his father's demise.

"The first batch of

photographs was the result of my exploration of the southern

region of Bangladesh. People are happier here, their faces

pleasant. They know how to smile," attests Tanjil.

He

later discovered that the more he explored the north, the

more he was confronted with people from whose faces the

signs of happiness simply got obliterated. "In the

deep north the food scarcity is such a persistent crisis

that people, especially the elderly are faced with severe

deprivation," Tanjil says. His physical journey as

well as the journey through the images that he records make

him something of an expert in this demographic. His batch

of photos has a strong anthropological significance. He

later discovered that the more he explored the north, the

more he was confronted with people from whose faces the

signs of happiness simply got obliterated. "In the

deep north the food scarcity is such a persistent crisis

that people, especially the elderly are faced with severe

deprivation," Tanjil says. His physical journey as

well as the journey through the images that he records make

him something of an expert in this demographic. His batch

of photos has a strong anthropological significance.

Tanjil remembers the first

encounter he marshaled with an elderly man. He says, "As

I failed to receive any knowledge or enlightenment from

my father, to compensate for what I was left out of, I began

to interact with Akkas Jamaddar, the oldest person in our

locality." And after talking to this man he found out

the core problem. "It is not that Akkas' family is

downtrodden, it is the unwillingness to care that lent him

his shabby look," affirms Tanjil who set out on his

photographic Odyssey for the next ten months on the trail

of elderly men and women.

It was not easy to strike

up a conversation with the elderly. Tanjil made an effort.

"I spent six days on a man, who at first took me for

someone sent by the NGOs and was unwilling to communicate,"

Tanjil reveals. He was told off by this man, who had said

to his face, "You want to photograph me? You want to

make money?"

It is always after he earned

the trust of the persons that he could click his camera.

"Without some sort of compassion between me and my

models, the possibility of unmasking the life within him

or her is impossible," says the photographer whose

earnestness made many a hard shell crack.

Tanjil treaded through all

kinds of localities. While he met people who were still

trying to eke out a living and valedictorian who took part

in the 1st World War, his own concept of human dignity and

knowledge went through a change. The one exceptional women

he met goes by the name of Joba, who devoted her entire

life in the service of a man, her husband, who resented

her for no particular reason even while in his deathbed.

“She says that he ended her life with a kick aimed at her,

and the whole community talks about it. Still she endearingly

remembers him,” says Tanjil.

Through his images Tanjilur

Rahman tries to affect a change in the attitude of a populace

who takes pride in being Eastern in its attitude. Because

it means caring for the elderly. But this can only be recognised

as a professed opinion. Reality tells a different tale.

The tale, which Tanjil exteriorised with compassion. Not

only did he give faces to these faceless people, but also

dignity to face the camera as who they are. And the hint

of smile only egged on the idea of the self-pride that Tanjil’s

works initiated. The most important thing of all is that

he recognised their wisdom that often eludes our human gaze

as we are firmly lodged in the area that can be recognised

as a blackhole called the 'generation gap'.

|

His

father's condolence meeting lasted for four hours. The speakers'

words did not work a gloomy spell on him as they usually

do in these circumstances, rather he was brought to the

realisation that the elderly in our society are treated

as non-persons. Towards these non-persons Tanjil developed

an empathy that set him to record their faces.

His

father's condolence meeting lasted for four hours. The speakers'

words did not work a gloomy spell on him as they usually

do in these circumstances, rather he was brought to the

realisation that the elderly in our society are treated

as non-persons. Towards these non-persons Tanjil developed

an empathy that set him to record their faces.  He

later discovered that the more he explored the north, the

more he was confronted with people from whose faces the

signs of happiness simply got obliterated. "In the

deep north the food scarcity is such a persistent crisis

that people, especially the elderly are faced with severe

deprivation," Tanjil says. His physical journey as

well as the journey through the images that he records make

him something of an expert in this demographic. His batch

of photos has a strong anthropological significance.

He

later discovered that the more he explored the north, the

more he was confronted with people from whose faces the

signs of happiness simply got obliterated. "In the

deep north the food scarcity is such a persistent crisis

that people, especially the elderly are faced with severe

deprivation," Tanjil says. His physical journey as

well as the journey through the images that he records make

him something of an expert in this demographic. His batch

of photos has a strong anthropological significance.