| |

Another

Garment Factory Tragedy:

Could it have been averted?

AASHA

MEHREEN AMIN and AHMEDE HUSSAIN

It

started out as any normal workday for the over 3,000

workers from six garment factories jam-packed in Misco

Supermarket complex at Mirpur's Dares Salam Road. But

only about a couple hours later complete mayhem replaced

what would have been an ordinary morning. It

started out as any normal workday for the over 3,000

workers from six garment factories jam-packed in Misco

Supermarket complex at Mirpur's Dares Salam Road. But

only about a couple hours later complete mayhem replaced

what would have been an ordinary morning.

At

around 10:30 a.m. a transformer near the building burst

and sparks could be seen flying in all directions. A

religious programme organised by Anjumane Rahmaniya

Mayeenia Maiz Bhandari was in full swing next to the

building completely taking over the narrow alley. The

roofed dais constructed for the programme to take place

started smoking up as the sparks set a part of it on

fire. Then a pile of waste cloth from the factories

caught fire and the smoke reached the verandah adjacent

two garment factories --Shifa Apparels and Omega Sweaters.

Someone started screaming 'fire!' All hell broke loose.

Men and women most in their teens and early twenties,

made a run for the main staircase, a narrow stairway

barely five feet in width. By now the word had spread

all over the building and panicked workers from all

six factories were running for their lives. Supervisors

tried to tell them not to panic. Dil Mohammad, general

manager of Omega Sweaters told his workers that the

fire was actually outside the building and that they

should all go back to work. But it was too late. While

some workers went through the emergency exits located

behind the building, most of them rushed through the

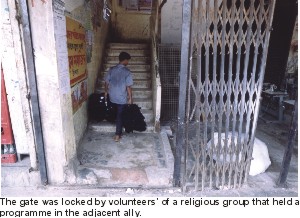

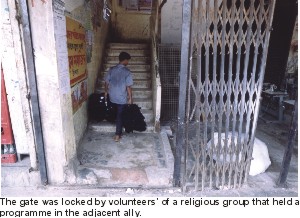

main stairway only to find that the gate was locked.

'Volunteers' of the religious 'mehfil' had taken it

upon themselves to keep the gate shut so that their

programme could go on without any disturbance from the

factories. This proved to be the deciding blow for seven

young women who were trampled to death in the ensuing

stampede. Fifty others were injured.

Among

the dead were 17-year-old Rina Akhter from Pabna who

had just started work at Omega Sweater Factory from

this January and Monira Begum, a 30-year-old married

woman from Tangail who worked as a wheeling operator

in the same factory. The other victims of what seems

to be an avoidable tragedy were all from Shifa Apparels:

40-year-old Khadeja Begum from Chandpur, 26-year-old

Begum from Netrokona, 30-year-old, Amena Begum from

Patuakhali, 15-year-old Parveen Akhter from Netrokona,

30-year-old Munira and 25-year-old Moina. "It is

still quite unreal to me," says Dil Mohammad, General

Manager of Omega Sweaters. "I kept telling them

there was nothing to fear as there was no fire inside

the building; the fire had been put out by six fire

extinguishers but they still panicked." Among

the dead were 17-year-old Rina Akhter from Pabna who

had just started work at Omega Sweater Factory from

this January and Monira Begum, a 30-year-old married

woman from Tangail who worked as a wheeling operator

in the same factory. The other victims of what seems

to be an avoidable tragedy were all from Shifa Apparels:

40-year-old Khadeja Begum from Chandpur, 26-year-old

Begum from Netrokona, 30-year-old, Amena Begum from

Patuakhali, 15-year-old Parveen Akhter from Netrokona,

30-year-old Munira and 25-year-old Moina. "It is

still quite unreal to me," says Dil Mohammad, General

Manager of Omega Sweaters. "I kept telling them

there was nothing to fear as there was no fire inside

the building; the fire had been put out by six fire

extinguishers but they still panicked."

The

recent disaster took place at a time when at least on

record most factories go through fire drills and try

to maintain minimum safety measures like keeping fire

extinguishers, fire fighting teams etc. to adhere to

BGMEA (Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters

Association) directives. These have been prompted by

international pressure regarding safety standards. But

in spite of having a fire drill two times a month, according

to Omega's general manager, two of its workers were

crushed to death along with five others from Shifa Apparels.

Garment

factories have been forced to take such measures, which

are far from being full-proof, after several tragedies

over the last several years.

In

November 2000, 45 garment workers were killed and 100

injured in a factory fire in Narshingdi caused by an

electrical short circuit. Among the victims were 10

children. Four workers were burnt alive, others suffocated

or were electrocuted or trampled in the stampede. The

stairwell was so crowded that workers

tried to break open the windows and throw themselves

out. Some were impaled on the pointed tops of the iron

buildings surrounding the factory. Again the collapsible

gates of the building were locked and the only route

of escape was closed. In

November 2000, 45 garment workers were killed and 100

injured in a factory fire in Narshingdi caused by an

electrical short circuit. Among the victims were 10

children. Four workers were burnt alive, others suffocated

or were electrocuted or trampled in the stampede. The

stairwell was so crowded that workers

tried to break open the windows and throw themselves

out. Some were impaled on the pointed tops of the iron

buildings surrounding the factory. Again the collapsible

gates of the building were locked and the only route

of escape was closed.

On

August 8, 2001, 24 garment workers were killed again

in a stampede due to a false alarm. The building housed

four separate factories with about 2,600 workers. When

the workers tried to reach the main gates and emergency

exits, they found both northern and southern gates locked.

Actually there were only two emergency exits, the stairways

were narrow and there were no emergency lights in case

of power failure. When the alarm went off the main electrical

switch was shut off and the workers ran along the stairs

in darkness. Many people did not even know that there

were alternative exits.

In

August 1999, a garment factory fire killed 12 workers.

Around 150 night shift workers who were sleeping in

the factory woke up choking in smoke with the factory

doors locked. Most of the trapped workers had to break

down a third floor wall or climb down to escape.

After

the August '99 incident, the government and factory

owners made bold statements on the need for strict adherence

to safety rules. But in spite of the then PM's publicised

grief, shock and sympathy for the loss of lives, her

government offered a paltry sum of 500 Takas and 25

kg of rice to each victim's family.

On

paper the BGMEA has a whole list of safety measures

each garments factory must adhere to. The BGMEA's safety

cell has a monitoring team that provides training to

factory staff and workers on fire safety methods and

regularly inspects factories according to Md. Ataur

Rahman, Senior Deputy secretary, BGMEA. "We have

a checklist of all the safety measures a factory should

have; if there is a discrepancy we make note of it and

take measures appropriately," says Rahman. This

may be in the form of loss of membership from BGMEA,

which however, has not happened till date. "The

team practically shows how to put out a fire, how to

use fire extinguishers to the factory management. Fire

drills are formed with 3 teams consisting of workers

and staff. They include six persons for fire fighting,

six for rescue and six to administer first aid. We record

how long it takes everyone to go downstairs, whether

all of them could come out and so on," Rahman explains.

Every factory he adds has a register to monitor the

drill quality. "If there are flaws, for instance

if goods block the staircase or if the wiring system

is faulty, we report this to the BGMEA," says Rahman.

If factories do not comply with the standards set by

the BGMEA, it can withdraw benefits of the member or

even suspend the factory. But usually the factory owners

come around and introduce the measures according to

Rahman. On

paper the BGMEA has a whole list of safety measures

each garments factory must adhere to. The BGMEA's safety

cell has a monitoring team that provides training to

factory staff and workers on fire safety methods and

regularly inspects factories according to Md. Ataur

Rahman, Senior Deputy secretary, BGMEA. "We have

a checklist of all the safety measures a factory should

have; if there is a discrepancy we make note of it and

take measures appropriately," says Rahman. This

may be in the form of loss of membership from BGMEA,

which however, has not happened till date. "The

team practically shows how to put out a fire, how to

use fire extinguishers to the factory management. Fire

drills are formed with 3 teams consisting of workers

and staff. They include six persons for fire fighting,

six for rescue and six to administer first aid. We record

how long it takes everyone to go downstairs, whether

all of them could come out and so on," Rahman explains.

Every factory he adds has a register to monitor the

drill quality. "If there are flaws, for instance

if goods block the staircase or if the wiring system

is faulty, we report this to the BGMEA," says Rahman.

If factories do not comply with the standards set by

the BGMEA, it can withdraw benefits of the member or

even suspend the factory. But usually the factory owners

come around and introduce the measures according to

Rahman.

Despite

such apparent good intentions why have they failed to

stop tragedies like the recent incident in Mirpur? Professor

of BUET and architect Dr. Nizamuddin Ahmed has done

much research on fire safety in building construction.

He says it is basically because these buildings have

not followed proper architectural norms that such horrible

mishaps continue to occur.

"Most

of the garment factories in the city are using buildings

that are built primarily either for residential or commercial

use. The landlords and, in cases, the factory owners,

just break down the walls on the floor of a particular

building to turn it into a garment factory," Dr

Nizam says. We architects, he continues, believe in

compartmentalisation of the floors. It is particularly

important when fire breaks out, because in a compartmentalised

building it is easy to put out a fire, as it does not

get the chance to spread out.

Building

Construction Rules 1996, which were enacted eight years

ago are also quite vague. The law requires all building

owners to build at least one staircase every 75 feet.

"It is erroneous because the number of stairs in

a building depends on the volume of traffic of that

particular building. A wholesale law regulating the

number of stairs for every type of building is illogical

as it is meant to differ according to that particular

building's use. You cannot enact laws that can place

hospitals, residential buildings and industrial complexes

under the same guidelines," Dr Nizam points out.

The law is not at all specific about the numbers and

types of fire fighting tools a particular industrial

complex is required to keep. "It is strange because

the number and type of devices to put out a fire will

invariably vary from building to building," he

says.

To

prevent incidents of fire breaking out every factory

floor should have different floor-in-charges for every

alternate working day, Dr Nizam suggests. So, when fire

breaks out, the in-charge will guide the co-workers,

along with the people properly trained, to the place

of safety. We have to keep in mind that fire spreads

pretty quickly; people must be able to escape to a safe

place within 2.5 minutes, the architect says. To

prevent incidents of fire breaking out every factory

floor should have different floor-in-charges for every

alternate working day, Dr Nizam suggests. So, when fire

breaks out, the in-charge will guide the co-workers,

along with the people properly trained, to the place

of safety. We have to keep in mind that fire spreads

pretty quickly; people must be able to escape to a safe

place within 2.5 minutes, the architect says.

The

escape routes that are being built by some factories

are lanky and steep; and have become a misnomer for

fire escape. "Some architects in our country think

a fire escape is a thin staircase that is to be hidden

away from people's eyes. I call them the draftsmen of

the clients, because they only blindly follow whatever

the clients' say. Just think once what will happen if

someone is unable to move in a

melee. What if 3000/5000 people just come down in a minute

or two during a fire?" Dr Nizam asks. All the staircases,

including the fire escapes, should be built and used as

normal staircases. Architectural norms require there should

be an exit door at the entrance to every floor's fire

escape. It should have the capacity to resist fire for

as long as 20 minutes, so that if fire breaks out on a

particular floor it will not spread anywhere else in that

building, he continues.

To

make it more complex, the country does not have any

emergency hotline. Like any other government organisation,

the Fire Brigade has its own numbers, which, Dr Nizam

thinks, no one remembers as "they are very difficult

to memorise." But, given the traffic in the city,

it is virtually impossible for the firemen to come and

put out the fire within 2.5 minutes. "No one should

completely depend on the fire service alone and every

production unit should have its own fire-fighting appliances,"

he says. Most of the factories in the country do not

have any smoke detector, let alone a fire sprinkler,

which is a necessity in every 10 square feet area of

a production complex. "I even doubt whether most

of the factories have adequate fire extinguisher or

not. You won't even find water in the bathrooms of some

of the factories forget having a reserve to put out

a fire," Dr Nizamuddin Ahmed says. To

make it more complex, the country does not have any

emergency hotline. Like any other government organisation,

the Fire Brigade has its own numbers, which, Dr Nizam

thinks, no one remembers as "they are very difficult

to memorise." But, given the traffic in the city,

it is virtually impossible for the firemen to come and

put out the fire within 2.5 minutes. "No one should

completely depend on the fire service alone and every

production unit should have its own fire-fighting appliances,"

he says. Most of the factories in the country do not

have any smoke detector, let alone a fire sprinkler,

which is a necessity in every 10 square feet area of

a production complex. "I even doubt whether most

of the factories have adequate fire extinguisher or

not. You won't even find water in the bathrooms of some

of the factories forget having a reserve to put out

a fire," Dr Nizamuddin Ahmed says.

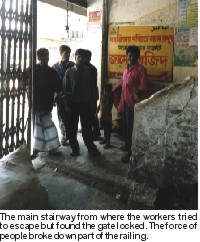

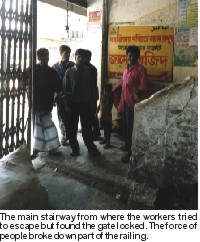

The

site where the recent tragedy took place clearly manifests

all the structural flaws that can lead to a disaster.

The main staircase where the stampede occurred is barely

5 feet wide. The wall end of the staircase was completely

broken down during the pandemonium. A quick glimpse

of Shifa Apparels (which lost five workers) gives a

picture of many small factories that have mushroomed

all over Mirpur and other areas. Workers have barely

a few inches between them, the air is suffocating with

so many people jam-packed. Machines, material and humans

are packed like sardines for many hours at a time and

even a small-scale mishap can lead to a catastrophe.

As for fire exits, the ones at this building are narrow

steel staircases on the outside of the building with

railings so low one wrong step will lead to a sure fall.

So much for a safe safety route! The

site where the recent tragedy took place clearly manifests

all the structural flaws that can lead to a disaster.

The main staircase where the stampede occurred is barely

5 feet wide. The wall end of the staircase was completely

broken down during the pandemonium. A quick glimpse

of Shifa Apparels (which lost five workers) gives a

picture of many small factories that have mushroomed

all over Mirpur and other areas. Workers have barely

a few inches between them, the air is suffocating with

so many people jam-packed. Machines, material and humans

are packed like sardines for many hours at a time and

even a small-scale mishap can lead to a catastrophe.

As for fire exits, the ones at this building are narrow

steel staircases on the outside of the building with

railings so low one wrong step will lead to a sure fall.

So much for a safe safety route!

Technically

all building construction in the city has to be done

with the approval from RAJUK (Rajdhani Unnon Kotripokhkho).

According to RAJUK laws, buildings in the city can be

built for residential or commercial purposes (offices).

But many garment factories have been built in such 'commercial

spaces' in complete violation of such regulations. How

did this happen? "While most of the rules are regularly

being flouted, the organisation turns a blind eye to

it. So, the buildings, which are built to house five

to 10 people, are now used for industrial purposes,"

Dr Nizam says. This, in turn, results in the use of

more electronic appliances like electric fans and machines

in a decompart-mentalised open space, which have made

the garment industries more prone to fire. Moreover,

he continues, the electricity lines are not properly

rooted in these buildings. Because of haphazard power

management, incidents of fire have been increasing,

he continues.

RAJUK

has recently announced 139 buildings in residential

areas of the city as being illegally constructed and

has warned that their lease agreements would be cancelled

if their position as residential buildings is not restored.

But this seems to have spared the scores of claustrophobic

garment factories all over Dhaka in areas such as Mirpur,

Gulshan, Old Airport road and Banani. Iqbaluddin Ahmed,

RAJUK's chairman, defends this strange discrepancy by

saying that RAJUK will not allow any new such factories

to crop up and that in any case nowadays the new ones

usually locate themselves in industrial areas. RAJUK

has recently announced 139 buildings in residential

areas of the city as being illegally constructed and

has warned that their lease agreements would be cancelled

if their position as residential buildings is not restored.

But this seems to have spared the scores of claustrophobic

garment factories all over Dhaka in areas such as Mirpur,

Gulshan, Old Airport road and Banani. Iqbaluddin Ahmed,

RAJUK's chairman, defends this strange discrepancy by

saying that RAJUK will not allow any new such factories

to crop up and that in any case nowadays the new ones

usually locate themselves in industrial areas.

Yet

the fact remains that existing factories continue to

thrive in residential areas because of RAJUK's indulgence

of an industry that has virtually placed the country

on the global map and created employment for thousands

of poor people. "International observers are very

particular about facilities for workers and new factories

must adhere to that to survive," says Iqbaluddin

Ahmed. Location of a garment factory, therefore, says

Ahmed, must be in an industrial area. Relocation seems

to be a buzzword at RAJUK, BGMEA and many big wigs of

the garment industry have built their factories outside

the city adhering to universal safety standards.

"We

cannot go on like this," says Md Ali Azim Khan,

chairman, standing committee on Safety Measures, BGMEA.

"Buyers are also very concerned about safety standards,"

says Khan, whose factory has been built on the outskirts

of the city. "We

cannot go on like this," says Md Ali Azim Khan,

chairman, standing committee on Safety Measures, BGMEA.

"Buyers are also very concerned about safety standards,"

says Khan, whose factory has been built on the outskirts

of the city.

But,

relocation, Khan adds, is very expensive, so smaller

factory owners are reluctant to move. It is quite impossible

for the small entrepreneurs to operate their industry,

as the rate of interest is really high in the capital

market.

"We

cannot force them to move but we advise them. We have

requested the government to give us a big space to set

up a garment village where all the factories can be

located. For instance we asked for the Adamjee Jute

Mills area but the price the government is offering,

Tk 2 lakh per katha, is too high," he

says. According to Khan unless the government helps

the garment factories with land and funds, relocation

may still be a far off possibility. "We

cannot force them to move but we advise them. We have

requested the government to give us a big space to set

up a garment village where all the factories can be

located. For instance we asked for the Adamjee Jute

Mills area but the price the government is offering,

Tk 2 lakh per katha, is too high," he

says. According to Khan unless the government helps

the garment factories with land and funds, relocation

may still be a far off possibility.

The

Ready Made Garments Sector accounts for 75% of Bangladesh's

export earnings and employs around 15 lakh people. Obviously

it is the most important sector of our economy. All

the more reason for the government to support the factories

by helping them to relocate and also make sure they

are safe working places. Garment factory owners who

reap the greatest benefits from the hard labour of their

workers cannot afford to make half-hearted attempts

to adhere to international safety standards. BGMEA has

decided to compensate the families of the victims of

the recent tragedy with Tk 1 lakh each. But human life,

cannot be priced.

|

|

It

started out as any normal workday for the over 3,000

workers from six garment factories jam-packed in Misco

Supermarket complex at Mirpur's Dares Salam Road. But

only about a couple hours later complete mayhem replaced

what would have been an ordinary morning.

It

started out as any normal workday for the over 3,000

workers from six garment factories jam-packed in Misco

Supermarket complex at Mirpur's Dares Salam Road. But

only about a couple hours later complete mayhem replaced

what would have been an ordinary morning. Among

the dead were 17-year-old Rina Akhter from Pabna who

had just started work at Omega Sweater Factory from

this January and Monira Begum, a 30-year-old married

woman from Tangail who worked as a wheeling operator

in the same factory. The other victims of what seems

to be an avoidable tragedy were all from Shifa Apparels:

40-year-old Khadeja Begum from Chandpur, 26-year-old

Begum from Netrokona, 30-year-old, Amena Begum from

Patuakhali, 15-year-old Parveen Akhter from Netrokona,

30-year-old Munira and 25-year-old Moina. "It is

still quite unreal to me," says Dil Mohammad, General

Manager of Omega Sweaters. "I kept telling them

there was nothing to fear as there was no fire inside

the building; the fire had been put out by six fire

extinguishers but they still panicked."

Among

the dead were 17-year-old Rina Akhter from Pabna who

had just started work at Omega Sweater Factory from

this January and Monira Begum, a 30-year-old married

woman from Tangail who worked as a wheeling operator

in the same factory. The other victims of what seems

to be an avoidable tragedy were all from Shifa Apparels:

40-year-old Khadeja Begum from Chandpur, 26-year-old

Begum from Netrokona, 30-year-old, Amena Begum from

Patuakhali, 15-year-old Parveen Akhter from Netrokona,

30-year-old Munira and 25-year-old Moina. "It is

still quite unreal to me," says Dil Mohammad, General

Manager of Omega Sweaters. "I kept telling them

there was nothing to fear as there was no fire inside

the building; the fire had been put out by six fire

extinguishers but they still panicked." In

November 2000, 45 garment workers were killed and 100

injured in a factory fire in Narshingdi caused by an

electrical short circuit. Among the victims were 10

children. Four workers were burnt alive, others suffocated

or were electrocuted or trampled in the stampede. The

stairwell was so crowded that workers

tried to break open the windows and throw themselves

out. Some were impaled on the pointed tops of the iron

buildings surrounding the factory. Again the collapsible

gates of the building were locked and the only route

of escape was closed.

In

November 2000, 45 garment workers were killed and 100

injured in a factory fire in Narshingdi caused by an

electrical short circuit. Among the victims were 10

children. Four workers were burnt alive, others suffocated

or were electrocuted or trampled in the stampede. The

stairwell was so crowded that workers

tried to break open the windows and throw themselves

out. Some were impaled on the pointed tops of the iron

buildings surrounding the factory. Again the collapsible

gates of the building were locked and the only route

of escape was closed.  On

paper the BGMEA has a whole list of safety measures

each garments factory must adhere to. The BGMEA's safety

cell has a monitoring team that provides training to

factory staff and workers on fire safety methods and

regularly inspects factories according to Md. Ataur

Rahman, Senior Deputy secretary, BGMEA. "We have

a checklist of all the safety measures a factory should

have; if there is a discrepancy we make note of it and

take measures appropriately," says Rahman. This

may be in the form of loss of membership from BGMEA,

which however, has not happened till date. "The

team practically shows how to put out a fire, how to

use fire extinguishers to the factory management. Fire

drills are formed with 3 teams consisting of workers

and staff. They include six persons for fire fighting,

six for rescue and six to administer first aid. We record

how long it takes everyone to go downstairs, whether

all of them could come out and so on," Rahman explains.

Every factory he adds has a register to monitor the

drill quality. "If there are flaws, for instance

if goods block the staircase or if the wiring system

is faulty, we report this to the BGMEA," says Rahman.

If factories do not comply with the standards set by

the BGMEA, it can withdraw benefits of the member or

even suspend the factory. But usually the factory owners

come around and introduce the measures according to

Rahman.

On

paper the BGMEA has a whole list of safety measures

each garments factory must adhere to. The BGMEA's safety

cell has a monitoring team that provides training to

factory staff and workers on fire safety methods and

regularly inspects factories according to Md. Ataur

Rahman, Senior Deputy secretary, BGMEA. "We have

a checklist of all the safety measures a factory should

have; if there is a discrepancy we make note of it and

take measures appropriately," says Rahman. This

may be in the form of loss of membership from BGMEA,

which however, has not happened till date. "The

team practically shows how to put out a fire, how to

use fire extinguishers to the factory management. Fire

drills are formed with 3 teams consisting of workers

and staff. They include six persons for fire fighting,

six for rescue and six to administer first aid. We record

how long it takes everyone to go downstairs, whether

all of them could come out and so on," Rahman explains.

Every factory he adds has a register to monitor the

drill quality. "If there are flaws, for instance

if goods block the staircase or if the wiring system

is faulty, we report this to the BGMEA," says Rahman.

If factories do not comply with the standards set by

the BGMEA, it can withdraw benefits of the member or

even suspend the factory. But usually the factory owners

come around and introduce the measures according to

Rahman. To

prevent incidents of fire breaking out every factory

floor should have different floor-in-charges for every

alternate working day, Dr Nizam suggests. So, when fire

breaks out, the in-charge will guide the co-workers,

along with the people properly trained, to the place

of safety. We have to keep in mind that fire spreads

pretty quickly; people must be able to escape to a safe

place within 2.5 minutes, the architect says.

To

prevent incidents of fire breaking out every factory

floor should have different floor-in-charges for every

alternate working day, Dr Nizam suggests. So, when fire

breaks out, the in-charge will guide the co-workers,

along with the people properly trained, to the place

of safety. We have to keep in mind that fire spreads

pretty quickly; people must be able to escape to a safe

place within 2.5 minutes, the architect says.  To

make it more complex, the country does not have any

emergency hotline. Like any other government organisation,

the Fire Brigade has its own numbers, which, Dr Nizam

thinks, no one remembers as "they are very difficult

to memorise." But, given the traffic in the city,

it is virtually impossible for the firemen to come and

put out the fire within 2.5 minutes. "No one should

completely depend on the fire service alone and every

production unit should have its own fire-fighting appliances,"

he says. Most of the factories in the country do not

have any smoke detector, let alone a fire sprinkler,

which is a necessity in every 10 square feet area of

a production complex. "I even doubt whether most

of the factories have adequate fire extinguisher or

not. You won't even find water in the bathrooms of some

of the factories forget having a reserve to put out

a fire," Dr Nizamuddin Ahmed says.

To

make it more complex, the country does not have any

emergency hotline. Like any other government organisation,

the Fire Brigade has its own numbers, which, Dr Nizam

thinks, no one remembers as "they are very difficult

to memorise." But, given the traffic in the city,

it is virtually impossible for the firemen to come and

put out the fire within 2.5 minutes. "No one should

completely depend on the fire service alone and every

production unit should have its own fire-fighting appliances,"

he says. Most of the factories in the country do not

have any smoke detector, let alone a fire sprinkler,

which is a necessity in every 10 square feet area of

a production complex. "I even doubt whether most

of the factories have adequate fire extinguisher or

not. You won't even find water in the bathrooms of some

of the factories forget having a reserve to put out

a fire," Dr Nizamuddin Ahmed says.  The

site where the recent tragedy took place clearly manifests

all the structural flaws that can lead to a disaster.

The main staircase where the stampede occurred is barely

5 feet wide. The wall end of the staircase was completely

broken down during the pandemonium. A quick glimpse

of Shifa Apparels (which lost five workers) gives a

picture of many small factories that have mushroomed

all over Mirpur and other areas. Workers have barely

a few inches between them, the air is suffocating with

so many people jam-packed. Machines, material and humans

are packed like sardines for many hours at a time and

even a small-scale mishap can lead to a catastrophe.

As for fire exits, the ones at this building are narrow

steel staircases on the outside of the building with

railings so low one wrong step will lead to a sure fall.

So much for a safe safety route!

The

site where the recent tragedy took place clearly manifests

all the structural flaws that can lead to a disaster.

The main staircase where the stampede occurred is barely

5 feet wide. The wall end of the staircase was completely

broken down during the pandemonium. A quick glimpse

of Shifa Apparels (which lost five workers) gives a

picture of many small factories that have mushroomed

all over Mirpur and other areas. Workers have barely

a few inches between them, the air is suffocating with

so many people jam-packed. Machines, material and humans

are packed like sardines for many hours at a time and

even a small-scale mishap can lead to a catastrophe.

As for fire exits, the ones at this building are narrow

steel staircases on the outside of the building with

railings so low one wrong step will lead to a sure fall.

So much for a safe safety route! RAJUK

has recently announced 139 buildings in residential

areas of the city as being illegally constructed and

has warned that their lease agreements would be cancelled

if their position as residential buildings is not restored.

But this seems to have spared the scores of claustrophobic

garment factories all over Dhaka in areas such as Mirpur,

Gulshan, Old Airport road and Banani. Iqbaluddin Ahmed,

RAJUK's chairman, defends this strange discrepancy by

saying that RAJUK will not allow any new such factories

to crop up and that in any case nowadays the new ones

usually locate themselves in industrial areas.

RAJUK

has recently announced 139 buildings in residential

areas of the city as being illegally constructed and

has warned that their lease agreements would be cancelled

if their position as residential buildings is not restored.

But this seems to have spared the scores of claustrophobic

garment factories all over Dhaka in areas such as Mirpur,

Gulshan, Old Airport road and Banani. Iqbaluddin Ahmed,

RAJUK's chairman, defends this strange discrepancy by

saying that RAJUK will not allow any new such factories

to crop up and that in any case nowadays the new ones

usually locate themselves in industrial areas.  "We

cannot go on like this," says Md Ali Azim Khan,

chairman, standing committee on Safety Measures, BGMEA.

"Buyers are also very concerned about safety standards,"

says Khan, whose factory has been built on the outskirts

of the city.

"We

cannot go on like this," says Md Ali Azim Khan,

chairman, standing committee on Safety Measures, BGMEA.

"Buyers are also very concerned about safety standards,"

says Khan, whose factory has been built on the outskirts

of the city.  "We

cannot force them to move but we advise them. We have

requested the government to give us a big space to set

up a garment village where all the factories can be

located. For instance we asked for the Adamjee Jute

Mills area but the price the government is offering,

Tk 2 lakh per katha, is too high," he

says. According to Khan unless the government helps

the garment factories with land and funds, relocation

may still be a far off possibility.

"We

cannot force them to move but we advise them. We have

requested the government to give us a big space to set

up a garment village where all the factories can be

located. For instance we asked for the Adamjee Jute

Mills area but the price the government is offering,

Tk 2 lakh per katha, is too high," he

says. According to Khan unless the government helps

the garment factories with land and funds, relocation

may still be a far off possibility.