| |

Kodak Moments out of a Nightmare

Mustafa

Zaman

Call

it the twenty-first century Vietnam, or the latest morass

of a land that the US has been struggling to stable its

foot upon, Iraq remains a steamy issue even after more than

one year of occupation. It is even getting steamier, as

missteps of the occupying forces are being scrutinised in

the international media. The latest outburst of information,

courtesy of the images that "illegally got in the hands

of the press" -- as the man at the top, Rumsfeld, The

Defense Secretary of the US, dubbed it during the first

senate inquiry, -- has opened up a whole new frontier. New

in the sense that, so far, the world at large, has been

unexposed to such vile means of torture. The American variant

has certainly carried the shock value in the highest dose. Call

it the twenty-first century Vietnam, or the latest morass

of a land that the US has been struggling to stable its

foot upon, Iraq remains a steamy issue even after more than

one year of occupation. It is even getting steamier, as

missteps of the occupying forces are being scrutinised in

the international media. The latest outburst of information,

courtesy of the images that "illegally got in the hands

of the press" -- as the man at the top, Rumsfeld, The

Defense Secretary of the US, dubbed it during the first

senate inquiry, -- has opened up a whole new frontier. New

in the sense that, so far, the world at large, has been

unexposed to such vile means of torture. The American variant

has certainly carried the shock value in the highest dose.

How

does a country with a knack for seeing itself as an example

of democracy and liberal practices make it this far? The

issue must be confronted from many directions. One clear

direction would be to ask what price does a nation pay for

playing police to the world? Especially when policing in

today's world that has unwittingly created pockets of resistance,

either in the form of terrorist outfits or in alternative

movements, against the monolithic practice of modernism,

is such a Herculean task. Confrontation with newer forces

is inevitable. Who realised that a man like Moqtada Al Sadre

would become a key factor in Iraq? A force that is showing

no signs of let up even in the face of the fiercest American

offensive!

War

not only begets war but also a series of unknown maladies.

And lives are not the only casualty of war. The strange

side of it, an aspect that often remains under wrap, is

that great wars leave both the sides with their human qualities

often snubbed and at times completely effaced. The crusaders

of the mediaeval era often took pleasure in raping and plundering

their enemy. The impact of war on the collective psyche

is something no one has any control over. It is the beast

that unleashes other beasts. After having fought several

wars in foreign lands, Americans are now paying the price.

They are finding it hard going in fighting the demons that

twist and lurch in their own fat belly. What war does to

the combating soldiers' psyche is something that is obvious

and well documented in the West. But that it opens up avenues

to depravities are something that still remains an underrated

issue. The American soldiers in Iraq have changed that.

In the post Abu Ghraib world, it seems, nothing is left

unexplored that has the capacity to jolt.

The

war against terrorism, like the holy wars of the past, is

no exception in its sinister capacity to spawn psychic disturbances

that lead to more sinister happenings. The war in Iraq,

that started purportedly to quell terrorism and to oust

a dictator, and now pretends to bring the fruit of Western

democracy to the land of oil, finally shows its inner composition.

What went on in the name of interrogation at the Abu Ghraib

prison is a sample of the lowest humans can sink to. The

sheer 'inventiveness' to subject enemies to such physical

degradation is something that will remain a nightmare in

the history of war and will provide scope to study human

behaviour in extreme conditions. The

war against terrorism, like the holy wars of the past, is

no exception in its sinister capacity to spawn psychic disturbances

that lead to more sinister happenings. The war in Iraq,

that started purportedly to quell terrorism and to oust

a dictator, and now pretends to bring the fruit of Western

democracy to the land of oil, finally shows its inner composition.

What went on in the name of interrogation at the Abu Ghraib

prison is a sample of the lowest humans can sink to. The

sheer 'inventiveness' to subject enemies to such physical

degradation is something that will remain a nightmare in

the history of war and will provide scope to study human

behaviour in extreme conditions.

Is this

behavioural bankruptcy all pervasive? Or is it a faction

that went berserk and acted badly on their own? Before we

even ponder these questions, one lesson that can be learnt

is that the great powers thrive in things that are brutal

and inexplicable. Meanwhile, the whole affair provides us

with a new ground of anthropological significance -- a whole

new field of study of human behavior now has opened up.

According to the accused soldiers, they were 'simply' engaged

in carrying out orders. But the results were norm defying

for sure, and of-course like fine art -- form braking.

But

before equating it with the arts and performances that are

also shocking and norm defying, one must seek to contextualise

it. Is it a terminal deformity of our civilisation that

finally brings out the basest of instincts in humans? One

of the soldiers, a woman, whose presence was ubiquitious

in the first batch of pictures, said she was just carrying

out orders. She did not behave any different from her male

counterparts. All the army officials in charge of the interrogations,

including women, looked similar, basking in their army-training

induced maleness. Women personnel looked devoid of their

femininity. Their antics seemed in conformity with the aggressiveness

that they all shared. Even their countenances were masculine,

and their actions bore the brand of depravity marked by

transgressions verging on the fascistic.

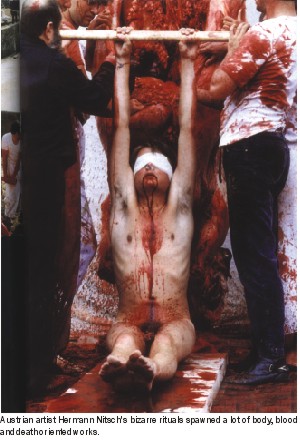

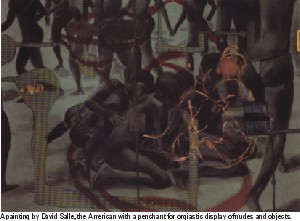

One

striking feature of the images that had been smuggled out

of army hands, both still and moving, is that they bear

a strong resemblance both to art and to movies to pornography

produced by a culture that crossed all conceivable bounds.

At least the index of the last forty years or so illustrates

a dark America, taking a strong liking to, if not immersed

deeply in, sado-masochism and anything that is brutal. The

obsession with the brutish is an aspect that moved many

an artist. The video installations by trail-blazing artists

like Bruce Newman, performances by Cindy Sherman and many

others that followed them in the '90s, as well as the recent

images of torture, are visual indicators of a culture, one

that lost faith in everything.

The

principle of getting pleasure by shocking others, or by

inflicting pain is an old idiom, with the West it often

marries the expression of art, or should one say anti art

that flourished to address issues of sex, gender, aids and

most of all alienation.

Perhaps

art that tackles brutality has different functions in the

society. But it also reveals, as does the willingness on

the part of the participating US solders, an obsession for

what is base and diabolic. The soldiers surpassed all other

genres with their form. In their hands two intentions melded,

one of staging a live and brutal drama, the other of keeping

a record for posterity. The first usually is the field of

the artists of gore, and the latter is the obsession of

the journalists. The act of the soldiers were two kinds

of expertise rolled into one.

Torture

is a confirmation of negating the enemy fully with a vengeance.

The American soldiers surely needed to show it to their

fellow countrymen how they successfully participated in

the piece of the action that aimed to humiliate the enemy

and they felt they needed hard evidence of their deed. How

else would one understand the utility of the photographs

and videos? The act of queuing for photo opportunities alongside

dead Iraqis was the ultimate kick that redefines the relation

between the victor and the vanquished. It also surpasses

all morbid art produced in the West in its shock value;

even those that used neatly composed parts of cadaver as

elements. Torture

is a confirmation of negating the enemy fully with a vengeance.

The American soldiers surely needed to show it to their

fellow countrymen how they successfully participated in

the piece of the action that aimed to humiliate the enemy

and they felt they needed hard evidence of their deed. How

else would one understand the utility of the photographs

and videos? The act of queuing for photo opportunities alongside

dead Iraqis was the ultimate kick that redefines the relation

between the victor and the vanquished. It also surpasses

all morbid art produced in the West in its shock value;

even those that used neatly composed parts of cadaver as

elements.

A culture,

or what is wrong with a culture, manifests not only in the

arts and the civil lives of a nation, but also in the form

of torture. Even the army operations provide an index. It

is something that comes out in the open all by itself.

So far,

the seamy side of American lives has never been a staple

for the international press. They, as well as their lives

have never been scrutinised the way we always scrutinise

the images produced by the artists and, at present, by the

army personnel. The world's safest haven for market economy

is known as the land of opportunity, but one needs to have

an open eye to discover what lies under the veneer of the

beautifully laid out physical environment. We are well acquainted

with the fruits of American democracy, but, it seems, that

the world, to an astonishing degree, simply never took a

good look at the scale of skin bias, domestic violence,

child molestation, and the serial rape and killing that

taint America. And one can always add to that the unholy

interest of the Americans in their serial murderers and

killers.

Surely,

these are not the only stuff that America is made of. But

they certainly correspond to the mindset that in the name

of fighting the worst enemy of this civilisation has actually

done more harm to it. There are a lot of indicators that

point to a million of good things about the average American.

But the pictures taken in Abu Ghraib are an ultimate reminder

of the fact that nationalism, if taken to its extreme, can

take a sinister form.

|

Call

it the twenty-first century Vietnam, or the latest morass

of a land that the US has been struggling to stable its

foot upon, Iraq remains a steamy issue even after more than

one year of occupation. It is even getting steamier, as

missteps of the occupying forces are being scrutinised in

the international media. The latest outburst of information,

courtesy of the images that "illegally got in the hands

of the press" -- as the man at the top, Rumsfeld, The

Defense Secretary of the US, dubbed it during the first

senate inquiry, -- has opened up a whole new frontier. New

in the sense that, so far, the world at large, has been

unexposed to such vile means of torture. The American variant

has certainly carried the shock value in the highest dose.

Call

it the twenty-first century Vietnam, or the latest morass

of a land that the US has been struggling to stable its

foot upon, Iraq remains a steamy issue even after more than

one year of occupation. It is even getting steamier, as

missteps of the occupying forces are being scrutinised in

the international media. The latest outburst of information,

courtesy of the images that "illegally got in the hands

of the press" -- as the man at the top, Rumsfeld, The

Defense Secretary of the US, dubbed it during the first

senate inquiry, -- has opened up a whole new frontier. New

in the sense that, so far, the world at large, has been

unexposed to such vile means of torture. The American variant

has certainly carried the shock value in the highest dose.

The

war against terrorism, like the holy wars of the past, is

no exception in its sinister capacity to spawn psychic disturbances

that lead to more sinister happenings. The war in Iraq,

that started purportedly to quell terrorism and to oust

a dictator, and now pretends to bring the fruit of Western

democracy to the land of oil, finally shows its inner composition.

What went on in the name of interrogation at the Abu Ghraib

prison is a sample of the lowest humans can sink to. The

sheer 'inventiveness' to subject enemies to such physical

degradation is something that will remain a nightmare in

the history of war and will provide scope to study human

behaviour in extreme conditions.

The

war against terrorism, like the holy wars of the past, is

no exception in its sinister capacity to spawn psychic disturbances

that lead to more sinister happenings. The war in Iraq,

that started purportedly to quell terrorism and to oust

a dictator, and now pretends to bring the fruit of Western

democracy to the land of oil, finally shows its inner composition.

What went on in the name of interrogation at the Abu Ghraib

prison is a sample of the lowest humans can sink to. The

sheer 'inventiveness' to subject enemies to such physical

degradation is something that will remain a nightmare in

the history of war and will provide scope to study human

behaviour in extreme conditions.  Torture

is a confirmation of negating the enemy fully with a vengeance.

The American soldiers surely needed to show it to their

fellow countrymen how they successfully participated in

the piece of the action that aimed to humiliate the enemy

and they felt they needed hard evidence of their deed. How

else would one understand the utility of the photographs

and videos? The act of queuing for photo opportunities alongside

dead Iraqis was the ultimate kick that redefines the relation

between the victor and the vanquished. It also surpasses

all morbid art produced in the West in its shock value;

even those that used neatly composed parts of cadaver as

elements.

Torture

is a confirmation of negating the enemy fully with a vengeance.

The American soldiers surely needed to show it to their

fellow countrymen how they successfully participated in

the piece of the action that aimed to humiliate the enemy

and they felt they needed hard evidence of their deed. How

else would one understand the utility of the photographs

and videos? The act of queuing for photo opportunities alongside

dead Iraqis was the ultimate kick that redefines the relation

between the victor and the vanquished. It also surpasses

all morbid art produced in the West in its shock value;

even those that used neatly composed parts of cadaver as

elements.