|

Cover

Story

Retracing

the Retracing

the

Journey of an

Artist

Mustafa Zaman

Reflections

on the Rear-view Mirror

"As a child, I had a sleeping intuition about art, had

a virgin mind with a provincial outlook on anything artistic,"

says Monirul Islam. The artist spent the first 18 years of

his life in Kishoreganj, a sleepy provincial town near Mymensingh.

As a child, he grew up copying portraitures of both literary

giants and stars of the silver screen and in designing the

school wall magazine. It was not until he graduated to the

high-school that he became an exponent of the popular culture

and ventured out into the world of banners, signboards and

rickshaw paintings. Once he did, "lacquer" became

the medium of choice. "Oil colour as a medium was unknown

to me as was the idea of any artwork other than rickshaw paintings

or banners. In that provincial backwater, having been given

the chance to paint a large sign for the local laundry itself

was a challenge, artistically," Monir says with his signature

down to earth sincerity. He painted a signboard featuring

Suchitra Sen, the screen goddess of that time, carrying laundry.

He picked up the icon from the few magazines that his father

subscribed to, and the rest was Monir's imagination; he was

then only 15.

Kishoreganj,

in the ’50s and the ’60s, could only boast of

few urban physical traces. "Yet there were those people

who gave their nod of appreciation to a meticulously done

portrait or a scenery," testifies Monir, whose first

mentor, whom he still remembers with much reverence, was Jogodish

Roy, the headmaster of his high-school.

"You will have to grow up to be an artist," was

the incessantly used phrase of this teacher. On every occasion

Monir showed his acumen in either decorating the classroom

during the Ramadan vacation or providing visual supplements

for the school wall magazine "Poruar Puthi"

(readers' manuscript), the headmaster reminded him of what

he should prepare for.

In

high-school, Monir struggled to cross the hurdles year after

year. However, he took painting to his heart, although he

had no inkling of what growing up to be an artist meant. "I

didn't feel any passion about becoming an artist, I could

not envisage a course that would lead me to the world of proper

artistic training or studies. To me the concept of art revolved

around the exquisitely done portraitures, the banners that

hung at the front of a cinema hall or a nicely painted rickshaw,"

recalls the painter, who, at the age of 61, has left behind

more than 30 years of his life spent as a professional artist

in a European country, Spain. In

high-school, Monir struggled to cross the hurdles year after

year. However, he took painting to his heart, although he

had no inkling of what growing up to be an artist meant. "I

didn't feel any passion about becoming an artist, I could

not envisage a course that would lead me to the world of proper

artistic training or studies. To me the concept of art revolved

around the exquisitely done portraitures, the banners that

hung at the front of a cinema hall or a nicely painted rickshaw,"

recalls the painter, who, at the age of 61, has left behind

more than 30 years of his life spent as a professional artist

in a European country, Spain.

Though

Kishoreganj, a small provincial town, was more akin to a village,

it had vibrant economic and cultural scenes. And the kishore

(young boy) Monir soon earned the epithet: "artist",

doing what he did best, producing images that people were

fond of.

The

first chance to try his hand at an innovative venture came

when he plastered a bamboo partition of their house with newspapers

and attempted a huge mural that explored a scene of riverine

Bangladesh. This painting was the crown on all the portraits,

banners and rickshaws he brought the touch of his talent to. The

first chance to try his hand at an innovative venture came

when he plastered a bamboo partition of their house with newspapers

and attempted a huge mural that explored a scene of riverine

Bangladesh. This painting was the crown on all the portraits,

banners and rickshaws he brought the touch of his talent to.

When the time came to enter Art College in

Dhaka, (the Institute of Fine Arts at present) he was caught

in something of a tug of war. At one end was the promise of

continuing with his passion for making art, and at the other,

there was the requirement of passing the Matriculation exam.

"I failed my Matriculation twice," Monir recalls,

"It was in the third attempt that I barely managed to

escape the same fate." And this freed him eternally from

the clasp of rote learning, which he never pursued seriously.

While Monir was having difficulties in his

studies, his parents thought a vocation of an electrician

might suit their son. Though Monir's mother was supportive

of her son's zeal for creating images, his father was distraught

over how his passion was impeding the prospect of doing well

at school. By the time Monir was allowed admission in Art

College, his father, Yusuf Ali Patwari, an officer at the

health department, had already passed away.

"He

died in 1960. He never approved of my creative adventures.

But at the end of his life he did realise that I was destined

to go wayward," the maestro reflects, whose childhood

ruminations brings into light how the artists of his generation

had to brave both social barriers and economic hardship to

become what they are today. Yet, now, things look sweeter

in retrospect as art was then a passion for both the artists

and its connoisseurs. "I never got paid for what I did,

I thought it was a privilege to be asked by somebody to do

a piece," Monir reflects. "He

died in 1960. He never approved of my creative adventures.

But at the end of his life he did realise that I was destined

to go wayward," the maestro reflects, whose childhood

ruminations brings into light how the artists of his generation

had to brave both social barriers and economic hardship to

become what they are today. Yet, now, things look sweeter

in retrospect as art was then a passion for both the artists

and its connoisseurs. "I never got paid for what I did,

I thought it was a privilege to be asked by somebody to do

a piece," Monir reflects.

On

the Corridor of Creativity

The mode of artistic production changed after the entry into

Art College in 1961. "I used to draw a lot, my teacher

Shafiuddin Ahmed will testify that I was a workoholic,"

Monir recently related to a journalist. Today in his 60s he

remains one of the most prolific artists alive.

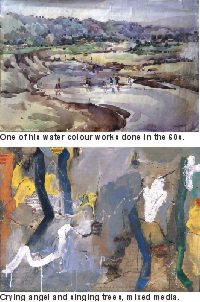

He

began to sell his works early on. During his study at Art

College, the watercolour studies kept piling up. After diligent

ventures outdoors day in and day out, he ended up with the

most number of works. "I used to sell watercolour works

for Tk 20 to 40 each. And the buyers, mostly foreigners, used

to come to the college premises to take their pick,"

Monir recalls. He

began to sell his works early on. During his study at Art

College, the watercolour studies kept piling up. After diligent

ventures outdoors day in and day out, he ended up with the

most number of works. "I used to sell watercolour works

for Tk 20 to 40 each. And the buyers, mostly foreigners, used

to come to the college premises to take their pick,"

Monir recalls.

Dhaka,

back in the ’60s, was a hub of resources for an artist

trying to develop his skills outdoors. "Karwan Bazar

was in walking distance from where I used to reside, which

was at Kathal Bagan. The house I lived in used to be where

the Green Tower stands today. And Karwan Bazar was a village

of potters surrounded by water bodies and greenery,"

Monir reconstructs the Dhaka that consisted of many such villages

on its outskirts. The now famous artist, in his early years

of art training, took refuge at his maternal uncle's house,

where an overabundance of family members and shortage of pillows

forced each to get hold of a pillow early on in the evening

to be sure of a good night's sleep.

Later,

during his third year in college, Monir moved on to the hostel

that came into being at that time after years of demands from

the students. A brilliant student at Art College, where he

never stood second, Monir's future course was already sealed

as an artist, and on top of that, he joined the teaching contingent

in the Department of Drawing and Painting after his graduation

in 1966. He taught only for three years and left on a scholarship

for Spain in 1969, and after that, his path never swerved

to any other direction. Even when he came back in 1979 after

ten years in Madrid, going back to teaching was the last thing

he had in mind. Later,

during his third year in college, Monir moved on to the hostel

that came into being at that time after years of demands from

the students. A brilliant student at Art College, where he

never stood second, Monir's future course was already sealed

as an artist, and on top of that, he joined the teaching contingent

in the Department of Drawing and Painting after his graduation

in 1966. He taught only for three years and left on a scholarship

for Spain in 1969, and after that, his path never swerved

to any other direction. Even when he came back in 1979 after

ten years in Madrid, going back to teaching was the last thing

he had in mind.

The

Artist at work

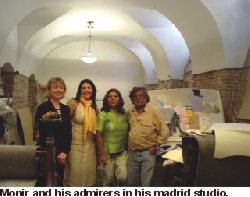

In the moderately large apartment at Dhanmondi, Monirul Islam

is bent over and engrossed in putting a coat of colour on

his tiny papers prepared for work. Even before venturing out

into the kitchen, he makes use of the time to finish the ground

for two new small paintings, both of which looked sombre compared

to the vibrantly coloured paintings that await the last touches

that may significantly transform them. However, even the unfinished

images carry signature Monir brilliance.

What

is this signature about? Is it a conscious effort to entrap

the onlookers into a pictorial solution that thrive on beauty

alone? The artist denies having to resort to any such simple

ploy. He says "It is an unending quest. You find yourself

in a 'marathon' on a daily basis. It is a personal struggle

that goes on forever." And he emphatically states that

"without a 'personal vision', without a well-defined

'inner world', artistic skill yields nothing but plain good

pictures.”

As

an artist anchored in the tradition of Spanish "Informal"

art, Monir recalls the Spanish adage -- "El artista

nace pero no se hace” (artists are born, not made).

Perhaps by resorting to this age-old epigram he wants to elucidate

that what is artistic in human nature cannot be found in the

ability to represent reality or thoughts but in the personality

of each individual. "Picasso could at once paint in realistic

fashion and in Cubist style as he had a strong personality,"

Monir argues. However, honesty and dedication are the two

things that he believes are the essential qualities that go

into the making of great artists.

After

adding two more small works to the pile of the hundreds of

similar pieces with grounding in different hues, Monir sips

the coffee he brought in from Europe. Then he playfully dwells

on the plight of the artists while reflecting on his early

days in Spain. His protracted stay in Spain was an accident.

He was cautioned by his family members not to come back home

after the war broke out on the home front in 1971. After

adding two more small works to the pile of the hundreds of

similar pieces with grounding in different hues, Monir sips

the coffee he brought in from Europe. Then he playfully dwells

on the plight of the artists while reflecting on his early

days in Spain. His protracted stay in Spain was an accident.

He was cautioned by his family members not to come back home

after the war broke out on the home front in 1971.

The war of independence and his stay in Spain,

however, made him explore a whole new world of imagery based

on the scourge of war. "I was afflicted by the fact that

I was far away from the war that ravaged my country. The sense

of not being able to contribute to my country's birth was

gnawing at my conscience," he remembers ruefully.

Monir got engaged in a different kind of struggle

on a different kind of frontier – he struggled to formulate

a proper expression for his newly discovered medium of art,

"etching". When the war raged at his birthplace,

in Madrid, Spain, he found solace in creating pictures based

on that very scourge. It was a test for him to make etching

his pet medium, which would remain so for the rest of his

career.

He calls art "a cruel profession",

not only because he himself had to go through an ordeal to

prove his worth in a foreign land at an early stage, but also

because "once you are out of the academy, you are faced

with an uncertain future; few get to pursue art as a profession.”

Creation of art certainly locks an artist

in a tough cycle.Even Monir, a man who has accomplished so

much both in Spain and at home, are constantly struggling

"not to get trapped" in the process of regurgitation

-- going over the already treaded path -- repeating oneself,

in plain English.

As for the signs of the mental disquiet that

stem from the quest for newer pictorial solutions, Monir carries

them with gait. Even in his visage, the traces surface. Though

for a man who turned 60 on August 17 last year, he looks younger,

his eyes give the hint of drive and passion. Over the last

few years he lost the youthful vigour of his face, yet in

his soul he seems eternally anchored in candidness and verve.

In his Dhanmondi apartment, where he greets his admirers,

journalists and fellow artists both young and old with equal

enthusiasm and cordiality, paintings replace the furniture.

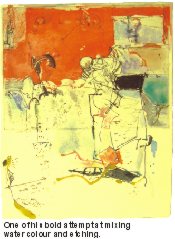

Though a solo show at the Gallery Shilpangan

is on, his apartment-cum-studio is still teeming with paintings.

It has been so since he delved into this media back in the

mid-1990s. From that point on, Monir, who back then already

attained mastery over printmaking by introducing a whole new

approach to it, has been exploring this other media with equal

might.

The

Spanish Rhapsody The

Spanish Rhapsody

Before October 10, 1969 – the day he left for Spain

on a scholarship to study traditional mural – Monir

was very much into painting, both oil and water colour. "It

was an inter-exchange programme between the two governments

that awarded him with this "30-dollar-a-month scholarship."

"Spain then was considered a folkloric country, but to

live there was cheap," recalls Monir.

It was in Spain that Monir first got introduced

to the beauty of etching, to which he later would submit his

artistic energy. "I may have done a few graphic works

in Dhaka, which included two tiny etchings, but that was only

to get acquainted with the method. It was in Spain that a

fellow scholar from the Philippines drew me into the magical

world of etching," Monir retraces his meteoric departure

from painting to graphics.

One evening in their Madrid hostel room the

Filipino etcher -- Virgilo Aviadio -- was looking at his own

colour-etching. For Monir, who used to share a room with the

etcher, it was a moment of awakening. "It was tempting

and surprising," Monir now reflects in retrospect. It

was Virgilo who after seeing his enthusiasm, asked Monir to

buy a cheaper plate to try his hand on etching and he also

chose for him a subject, which was self-portrait.

"Setting up an 'acid bath' in the hostel

was against the rule, but I arranged for it and worked on

my etching," remembers Monir. After that, "etching"

became a whole new world to explore and to conquer. And conquer

he did. After a decade in Madrid, not only was his transformation

to an 'etcher' complete but his artistic exploits made him

a man of considerable international fame. It went all uphill

from there.

Now, there is even a phrase to mark out the

way he works. In the Spanish art world, the result of his

"free-bite" technique is known as "Escuela

de Monir”. And its most striking feature is the casual

informality in agglomerating lines, shapes or colour fields.

He brought into graphics the freedom with which he used to

execute water colour paintings back home.

"Mustafa

Munwar showed us how to handle this medium with 'liberty'.

The non-academic approach I developed towards etching sprang

from the grounding I went through in college, which was based

on quick execution of water colour," says Monir, linking

his present work with that of his early studies. "Mustafa

Munwar showed us how to handle this medium with 'liberty'.

The non-academic approach I developed towards etching sprang

from the grounding I went through in college, which was based

on quick execution of water colour," says Monir, linking

his present work with that of his early studies.

What Monir refers to as the 'personal touch',

is something that one cultivates while drawing from all the

sources that attracts one the most. Monir is always gravitated

to "image that provokes", a quality that he often

finds in squiggles, textures and even a resonating line.

Reality is always a springboard for him. The

real experiences, visual and otherwise, always found their

way into his abstract compositions.

Monir is about sensibility, not at all about

style. "Style and technique are never the main concern,

it is the 'inner spirit' that matters," he declares.

This exteriorisation of the inner being is what makes his

creations so fraught with energy. And perhaps this is what

helped him go beyond the bounds of traditional art, defying

academic sets of rules.

In Madrid, during the first year of the '70s,

following the suggestion from his Filipino friend, he joined

the graphic studio "Group-15" as a printer. This

was an opportunity to rub shoulders with artists of international

stature. "Matta and Tapies used to come here to work,"

Monir recalls. But, as a printer, whose job is to help printmakers

to roll out prints, he and his friend were often looked down

upon.

It was the "elite artists" who worked

there, Monir was the printer who was trying to produce his

own work during the lull in the evening. No matter how his

works were considered by the working artists of Madrid –

where after the time of Goya and Fortuni, etching was in decline,

and modern masters like Juan Miro and Autoni Tapies only initiated

a revival in the mid-twentieth century – Monir went

on making prints whenever he had time. And it was the fetching

of a prize at a biennale in Lubjana, Yugoslavia, in 1977 that

astonished the establishment consisting of the "elite"

etchers. Before that, a prize from the Madrid Museum in 1972

catalysed Monir to pursue his dream -- to become an artist.

The printer gradually found his footing on

a foreign turf and established himself as a compatriot of

the famous names in the continent.

The

artist, who never considers himself to be "a Bangladeshi

artist”, now has the leverage to take a spin around

the world. His stints as a juror keep him busy transgressing

boarders across the globe. Yet he often sends his entry into

international shows as a Bangladeshi. "In the Cairo triennial,

I was a jury representing the country of Spain, but my artwork

was entered under the rubric Bangladesh. As an artist, I represented

my country of birth," explains Monir, whose international

fame never weighed heavily upon him.

Monir wears his achievements lightly, and

he knows how firmly his feet are lodged on the soil of his

motherland. "I don't feel much difference as I come back

to Bangladesh in regards to living and working, but the minute

I set my feet on the ground, a sensation grips me, which I

never feel any where else in the world," confesses Monir.

He

has seen Spain rising out of the deep slumber that resulted

from the misrules of one of the most hated ogres of the world

-- Franco – and the life that he is able to breathe

in his artworks, be it an etching or an acrylic on paper,

seems representative of the vigour that his country of residence

regained over the years. He

has seen Spain rising out of the deep slumber that resulted

from the misrules of one of the most hated ogres of the world

-- Franco – and the life that he is able to breathe

in his artworks, be it an etching or an acrylic on paper,

seems representative of the vigour that his country of residence

regained over the years.

It has been 35 years in Spain, where he has

sired a son, now a teenager with a passion for football, born

of his Spanish wife Mela, who is an etcher in her own right.

Monir is no longer an expatriate in an unknown terrain; he

has lived through the ups and downs and made it a point to

savour all that life had to offer. From the point of the cancellation

of his scholarship in 1972 (as East Pakistan dissolved so

did his scholarship) to the time when he bagged his first

international award, five long years were spent consolidating

his might, constructing a mode of art as well as reinventing

a Bangali psyche well adjusted to the characteristics unique

to the Mediterranean zone.

The individual signature, the anarchic state

of mind and the vehemence of passion that, in Monir's opinion

colours the cultural horizon of Spain, are the ingredients

that a Bangali can recognise well and be a party to. As the

maestro himself declares --"you can never really encounter

such passionate art from Japan", where discipline and

rules relegate works of art to mere decorations.

"Artists live in a state of violence,"

Monir declares, and explains how, by doing so, he also becomes

disassociated from the regular social life. However, he strongly

believes that alienation or withdrawal from everyday existence

is not an option for artists who would want to remain in touch

with what is real and palpable in life.

Zainul Abedin advised him "not to chase

a lame man”, and Monir took this to heart and at the

age of 61 he remains at the helm of his universe composed

of colour, lines and form, chasing a dream to explore newer

horizons.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|