|

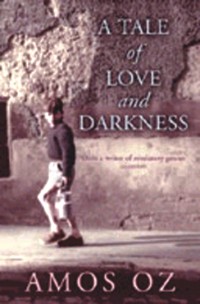

Book

Review

The

Burden of Bistory

Amos

Oz

Oz's

memoir, A Tale of Love and Darkness, thought to be the biggest-selling

literary work in Israeli history, is an exploration of why

his mother killed herself, and the effect on him, a sensitive,

intelligent boy growing up in Jerusalem during the last years

of the British mandate and the war of independence. It is

one of the funniest, most tragic and most touching books I

have ever read. I am a great admirer of Oz as a novelist,

of his spare, quiet portraits of intimacy between couples,

but here, in this long book, he reveals a huge talent for

the big narrative picture, for Dickensian character portraits

and an expert fusion of history and personal life. Oz's

memoir, A Tale of Love and Darkness, thought to be the biggest-selling

literary work in Israeli history, is an exploration of why

his mother killed herself, and the effect on him, a sensitive,

intelligent boy growing up in Jerusalem during the last years

of the British mandate and the war of independence. It is

one of the funniest, most tragic and most touching books I

have ever read. I am a great admirer of Oz as a novelist,

of his spare, quiet portraits of intimacy between couples,

but here, in this long book, he reveals a huge talent for

the big narrative picture, for Dickensian character portraits

and an expert fusion of history and personal life.

From the

outset the family bears down on you. His father, Ariyeh Klausner,

the thwarted academic in a land stuffed with the over-qualified

- "a sort of rootless, short-sighted intellectual with

two left hands". His grandfather, the follower of Ze'ev

Jabotinsky, the revisionist founding father of today's right-wing

Israeli politics: "He was a nationalist, patriot, a lover

of armies, victories and conquest, a passion-ate, innocent

minded-hawk... He had a weakness for everything grand, powerful

and gleaming - military uniforms, brass bugles, banners and

lances glinting in the sun, royal palaces and coats of arms.

He was a child of the 19th century, even if he did live long

enough to see three-quarters of the 20th century."

Here,

too, is the neighbourhood, obsessed with germs: "You

never actually managed to set eyes on an anti-semite or a

germ, but you knew very well they were lying in wait for you

on every side, out of sight." The city, Jerusalem, where

people schlepped along the streets: "If we picked up

our foot someone else might come along and snatch our little

strip of land. On the other hand, once you have lifted your

foot, do not be in a hurry to put it down again... time and

time again we have fallen into the hands of our enemies because

we put our foot down without looking where we were putting

them." Tel Aviv, spoken of almost confidentially, "as

though the city were some kind of crucial secret project of

the Jewish people", the sea "full of bronzed Jews

who could swim... Who had ever heard of swimming Jews?"

As he

grows up, the world outside the lower-middle class neighbourhood

of down-at-heel intellectuals opens up to reveal another population:

Jerusalem's middle-class Arabs. Taken to a tea party in the

home of a post office employee in honour of the British post-master

general, he goes into the garden and tries to impress a little

girl, puffed up with a sense of responsibility as a representative

of the Jewish people and of Zionism. Excited and already a

little in love, when she dares him to climb a mulberry tree

he instantly transforms himself from Jabotinsky to Tarzan,

from weedy yeshiva bocher to muscular Judaism, "the resplendent

new Hebrew youth at the height of his powers... a lion among

lions"; he finds an iron ball and chain at the top of

the tree, whirls it round his head like a lasso, loses control

over it, so that it lands with a bloody crash on the foot

of her little brother, who is toddling after a butterfly,

"and everything was silent all around you in an instant

as though you had been shut up inside an iceberg".

Oz's book

is a testament to a family, a time and a place. And throughout

it there is the voice of the child who, 50 years later, still

cries out for his dead mother.

This

article was first published in the Guardian

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|