|

Cover

Story

LEADING

WOMEN TO CHANGE LEADING

WOMEN TO CHANGE

On the

occasion of International Women's Day, SWM pays tribute to

a living legend in journalism and a pioneer in making women

visible.

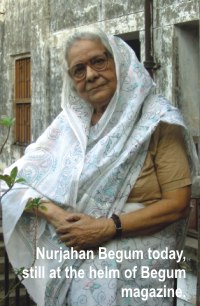

Nurjahan

Begum, editor of Begum magazine, began her career in the 1940s.

Journalism, activism, social work -- she has done it all,

and in a time people would have trouble imagining women doing

anything of the sort. To this day, she continues to help women

in towns and villages find a foothold in society through her

efforts to provide them with knowledge, a sense of awareness

and even identities as women writers, .

She goes to work every morning at 8 and returns home every

afternoon to her sprawling house in Puran Dhaka -- her home

since 1950 -- and continues the work she and her father started

decades ago. It is not an empire she manages now, but it has

served, for well over half a century, the purpose with which

it was begun -- to bring Bangali, especially Bangali Muslim

women, out from behind the closed walls of their homes and

into the wider, changing society of which they are part.

KAJALIE

SHEHREEN ISLAM

Nurjahan Begum

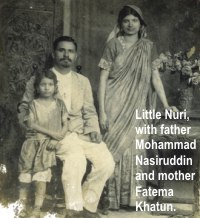

was born on June 4, 1925, as Nurun Nahar. Her father, renowned

journalist and editor of the monthly Shawgat, Mohammad

Nasiruddin, lived in Kolkata, while she, "Nuri",

lived with her mother, Fatema Begum, in Chalitatoli. After

an accident in which Nuri fell into a pond in the village

at the age of four, her father quickly had her move to Kolkata

with her mother, thinking his daughter would be far safer

there. Nurjahan Begum

was born on June 4, 1925, as Nurun Nahar. Her father, renowned

journalist and editor of the monthly Shawgat, Mohammad

Nasiruddin, lived in Kolkata, while she, "Nuri",

lived with her mother, Fatema Begum, in Chalitatoli. After

an accident in which Nuri fell into a pond in the village

at the age of four, her father quickly had her move to Kolkata

with her mother, thinking his daughter would be far safer

there.

"When

I came to Kolkata," reminisces Nurjahan Begum, "my

father, to the utter dismay of my mother, had my nose-pin

cut off and my hair sheared into a 'China bob' cut!"

Mohammad

Nasiruddin was a progressive man and he wanted his daughter

to be the same, easily fitting into Kolkata society and making

something of herself with a good, well-rounded education.

Little Nuri was taught nursery rhymes, poems and surahs

by her mother, and the Bangla, Arabic and English alphabet

by both her parents. Her father would bring home books and

magazines for Nuri to go through and look at pictures. Slowly,

she grew an interest in books. Even before she had learnt

to read properly, Nuri began to file her father's collection

of local and foreign publications just by looking at the pictures.

Delighted by her keen intelligence, Nuri's grandmother, Nurjahan,

decided to name her granddaughter after herself, and, from

then on, she became Nurjahan Begum. Mohammad

Nasiruddin was a progressive man and he wanted his daughter

to be the same, easily fitting into Kolkata society and making

something of herself with a good, well-rounded education.

Little Nuri was taught nursery rhymes, poems and surahs

by her mother, and the Bangla, Arabic and English alphabet

by both her parents. Her father would bring home books and

magazines for Nuri to go through and look at pictures. Slowly,

she grew an interest in books. Even before she had learnt

to read properly, Nuri began to file her father's collection

of local and foreign publications just by looking at the pictures.

Delighted by her keen intelligence, Nuri's grandmother, Nurjahan,

decided to name her granddaughter after herself, and, from

then on, she became Nurjahan Begum.

Nurjahan

Begum got admitted into Baby Class at Begum Rokeya's Sakhawat

Memorial School. She loved it there -- the playing, drawing,

arts and crafts. But when the workload got to be a little

too much after Class 2, her father shifted her to a school

near their home, Beltola Girl's School. In Class 5, however,

she went back to Sakhawat Memorial School from which she passed

her Matriculation in 1942. Nurjahan Begum remembers the school

fondly as the basis of her success later on in life. She had

the opportunity to learn to do a bit of everything there,

from singing, dancing and acting to cooking, sewing, drawing

and sports. In 1944, she passed her Intermediate examinations

in philosophy, history and geography, and, in 1946, her Bachelors

in ethics, philosophy and history from Lady Brabourne College. Nurjahan

Begum got admitted into Baby Class at Begum Rokeya's Sakhawat

Memorial School. She loved it there -- the playing, drawing,

arts and crafts. But when the workload got to be a little

too much after Class 2, her father shifted her to a school

near their home, Beltola Girl's School. In Class 5, however,

she went back to Sakhawat Memorial School from which she passed

her Matriculation in 1942. Nurjahan Begum remembers the school

fondly as the basis of her success later on in life. She had

the opportunity to learn to do a bit of everything there,

from singing, dancing and acting to cooking, sewing, drawing

and sports. In 1944, she passed her Intermediate examinations

in philosophy, history and geography, and, in 1946, her Bachelors

in ethics, philosophy and history from Lady Brabourne College.

Nurjahan

Begum was highly active throughout her school and college

life. "I had a wonderful childhood," she says. "We

did everything, from singing and dancing to acting."

She even wrote, directed and acted in college plays. "But

it was all within the walls of the school and college,"

she recalls. Nurjahan

Begum was highly active throughout her school and college

life. "I had a wonderful childhood," she says. "We

did everything, from singing and dancing to acting."

She even wrote, directed and acted in college plays. "But

it was all within the walls of the school and college,"

she recalls.

Most

Bangali and especially Muslim women of the time hardly stepped

out of the house, let alone sing and dance in public places.

The volatile days of 1947 had made it even more dangerous

for people living in this region.

"It

was under these circumstances," says Nurjahan Begum,

"that Begum was first published."

Nurjahan

Begum's father, Mohammad Nasiruddin, had wanted to bring women

into journalism. He therefore started an annual women's issue

of Shawgat in 1927. Every year, one issue of the

monthly would be dedicated exclusively to women, with writings

by women around the country that Mohammad Nasiruddin had to

put in much effort to collect. In 1945, the last issue of

Janana Mahal, came out. It seemed to Mohammad Nasiruddin

that one women's issue per year was not really doing much

to improve the situation of women in journalism and, in turn,

society. Thus, in 1947, a month before India's Partition,

weekly Begum was first published in Kolkata. Its

first editor was Begum Sufia Kamal, and acting editor, Nurjahan

Begum, who had already been working for Shawgat,

took over a few months later.

"It

was very difficult to bring out the publication at that time,"

recalls Nurjahan Begum. There was the problem of block and

type, of collecting ink and paper, and of transporting the

staff to and from the office during the communal riots. There

were not too many women writers and hardly any women photographers.

"But we still managed to bring out an issue every week,"

says Nurjahan Begum proudly. "It

was very difficult to bring out the publication at that time,"

recalls Nurjahan Begum. There was the problem of block and

type, of collecting ink and paper, and of transporting the

staff to and from the office during the communal riots. There

were not too many women writers and hardly any women photographers.

"But we still managed to bring out an issue every week,"

says Nurjahan Begum proudly.

After

three years in Kolkata, Begum moved to Dhaka, along

with Mohammad Nasiruddin, Nurjahan Begum and the rest of the

family.

The

response to Begum was enormous. Not only were women

from across the country writing letters and giving feedback

on the various writings published in the magazine, but many

men, Nurjahan Begum also reminisces about her father and her

husband, the two men who had the greatest influence on her

life and her success in her career. Her father was the one

to lead her down the path of journalism, though Nurjahan Begum

believes that passion for journalism -- or any profession

for that matter -- is inborn. "It cannot be forced upon

you," she says. All her life, she has simply done what

she always wanted to and what she felt she was meant to do. The

response to Begum was enormous. Not only were women

from across the country writing letters and giving feedback

on the various writings published in the magazine, but many

men, Nurjahan Begum also reminisces about her father and her

husband, the two men who had the greatest influence on her

life and her success in her career. Her father was the one

to lead her down the path of journalism, though Nurjahan Begum

believes that passion for journalism -- or any profession

for that matter -- is inborn. "It cannot be forced upon

you," she says. All her life, she has simply done what

she always wanted to and what she felt she was meant to do.

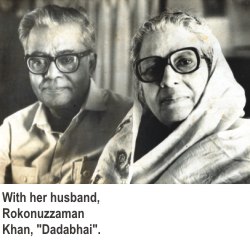

Her

husband, Rokonuzzaman Khan -- whom she married initially against

the will of her father -- later became a renowned journalist

in his own right. Popularly known as "Dadabhai"

later on, Khan had worked for Shawgat, and was later

editor of the literature and feature pages of the daily Ittefaq

as well as of “Kochikanchar Ashor" for

children.

After

her, says Nurjahan Begum, her daughters will take charge of

Begum. "Great changes will take place in their

hands," she says. "They won't accept bad writing.

They want good paper and colour in the magazine.” After

her, says Nurjahan Begum, her daughters will take charge of

Begum. "Great changes will take place in their

hands," she says. "They won't accept bad writing.

They want good paper and colour in the magazine.”

Her

eldest daughter, Flora Nasrin Khan Shakhi, did her Honours

and Master's in English Literature from Dhaka University.

Her younger daughter, Rina Yasmin Miti did her Honours and

Master's in Sociology from the same institution. They are

both married and work for Begum from time to time. Nurjahan

Begum has five grandchildren.

Begum

magazine is currently a monthly costing Tk. 10 (as opposed

to the 25 paisa it used to be sold at in the beginning), but

its editor has hopes of bringing it out as a weekly again.

Despite

the various problems she has faced over the years in bringing

out the magazine, from communal riots to postage problems,

Nurjahan Begum has not lost her zeal for her work or the profession

as a whole. She does not sit around simply praising the women

journalists today but rather worries about what still holds

them back. Despite

the various problems she has faced over the years in bringing

out the magazine, from communal riots to postage problems,

Nurjahan Begum has not lost her zeal for her work or the profession

as a whole. She does not sit around simply praising the women

journalists today but rather worries about what still holds

them back.

"Transport

problems and lack of security are the main problems facing

women journalists today," she says. "In the old

days, my friends and I used to go watch the 9 o'clock show

at the movies, which would end at midnight (albeit with her

father)," she recalls. "It can hardly be thought

of in our country today."

Women

are much more insecure and much less free today, believes

Nurjahan Begum. "Sometimes I wonder whether it's a conspiracy

to hold women back," she says.

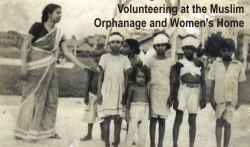

Besides

her journalistic career, Nurjahan Begum was also a dedicated

social worker. From volunteering at refugee camps during the

communal riots to working for the Muslim Orphanage and Women's

Home of which she was secretary, she became involved in social

work soon after finishing college. Later, she became member

and president of various women's organisations, including

the Wari Mohila Samity and the Narinda Mohila Samity. Through

these, she worked for primary education and structural activities

for children, first aid and adult education. She campaigned

and raised funds to help victims of natural disasters. Besides

her journalistic career, Nurjahan Begum was also a dedicated

social worker. From volunteering at refugee camps during the

communal riots to working for the Muslim Orphanage and Women's

Home of which she was secretary, she became involved in social

work soon after finishing college. Later, she became member

and president of various women's organisations, including

the Wari Mohila Samity and the Narinda Mohila Samity. Through

these, she worked for primary education and structural activities

for children, first aid and adult education. She campaigned

and raised funds to help victims of natural disasters.

Nurjahan

Begum did many things at a time when it was much less easy

than it is today, and what many women would not have the courage

or determination to do even today. With the help of her father,

she also established the Begum Club in 1954. Though now defunct,

in its time, the Club was a thriving organisation of women

from home and abroad getting together to discuss literature

and music, culture and society. Nurjahan Begum still has hopes

of reviving the Club. Nurjahan

Begum did many things at a time when it was much less easy

than it is today, and what many women would not have the courage

or determination to do even today. With the help of her father,

she also established the Begum Club in 1954. Though now defunct,

in its time, the Club was a thriving organisation of women

from home and abroad getting together to discuss literature

and music, culture and society. Nurjahan Begum still has hopes

of reviving the Club.

The

goal of Begum as a publication and of Nurjahan Begum

-- an institution in herself -- has always been to take women

forward, by informing and involving them in the society they

dwell in and contribute to. "There will always be problems

we will have to face," says Nurjahan Begum. "There

will always be religious conflict, social bindings and people

trying to hold us back. We can lie low for a while, but ultimately,

we have to move forward," she says. "It's the only

way to go."

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|

| |