|

Cover

Story

Cold

Facts

The summer is on full swing. As the mercury rises and we must brave another season of sweltering, enervating and dehydrating heat, what could be more welcome than a tall glass of juice or lassi deliciously chilled with loads of crushed ice? We see ice as a mere, though vital accessory to our favourite drink. Actually, it is something we consume that make it a food item; one that can be contaminated by germs resulting in food poisoning. There are many players in this chilling story. The consumers who are the ultimate victims, the vendors who sell drinks under unhygienic conditions, the ice manufacturers who make the product disregarding any health standard and finally the governmental bodies that should be monitoring the quality of ice that is consumed. Everyone is dangerously oblivious to the health hazard that contaminated ice poses. The summer is on full swing. As the mercury rises and we must brave another season of sweltering, enervating and dehydrating heat, what could be more welcome than a tall glass of juice or lassi deliciously chilled with loads of crushed ice? We see ice as a mere, though vital accessory to our favourite drink. Actually, it is something we consume that make it a food item; one that can be contaminated by germs resulting in food poisoning. There are many players in this chilling story. The consumers who are the ultimate victims, the vendors who sell drinks under unhygienic conditions, the ice manufacturers who make the product disregarding any health standard and finally the governmental bodies that should be monitoring the quality of ice that is consumed. Everyone is dangerously oblivious to the health hazard that contaminated ice poses.

AASHA MEHREEN AMIN

AHMEDE HUSSAIN

and

SHAMIM AHSAN

Photographs: Zahedul I Khan

Shaheen, one of the vendors selling papaya and Aloe Vera juice in Karwan Bazar, uses crushed-ice to chill the drinks he offers to his thirsty customers. Shaheen's ice turns a little yellowish at times because of the rusted trowel he uses to crush it. Shaheen, one of the vendors selling papaya and Aloe Vera juice in Karwan Bazar, uses crushed-ice to chill the drinks he offers to his thirsty customers. Shaheen's ice turns a little yellowish at times because of the rusted trowel he uses to crush it.

On a hot summer day, he and fellow vendors cater to a wide array of buyers, which include ordinary passers-by to office executives who work in different banks and newspaper offices nearby. "On an average I sell a 100 to 150 glasses of papaya juice," Shaheen says.

The vendor is not aware of food safety standards, let alone the health hazards that his drinks might create on the human body. "I don't know what type of water they use to make ice; it must be tap water," Shaheen says.

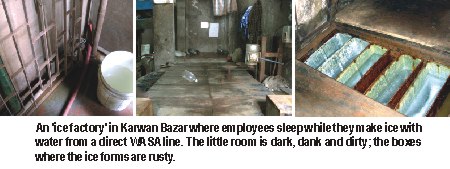

A big block of ice is sold at Tk.60. The factory, from which vendors like Shaheen and most of the confectioneries in the area buy ice, is a small room that reeks of human body odour.

There is a faucet at the entrance to the room from which tap water pipes to the underground reservoir. "For the supply of water we rely on WASA," says Ali Hossain, owner of the factory. He also believes it is safe to produce ice from tap water, as he says, "I do not think it is necessary to boil water. I have been doing it like this for years".

He also boasts that his ice will not melt away that easily as he "throws in salt into the tanks" where the water is freezed.

The aluminium receptacles that Hossain's workers use to make slabs of ice have become reddish-brown from their exposure to air and moisture. Although he claims that his men wash the iceboxes every two months, the 'factory' itself is far from being clean.

Both workers sleep in the room, on a wooden corner of the machine. It occupies practically the whole room; and, like the iceboxes that the workers put into it, the machine is corroded with rust. "I bought it 20 years ago," Hossain confesses. Both workers sleep in the room, on a wooden corner of the machine. It occupies practically the whole room; and, like the iceboxes that the workers put into it, the machine is corroded with rust. "I bought it 20 years ago," Hossain confesses.

Around a mile down the factory, near Farmgate, in a makeshift shop built on a drain, Hossain showcases chunks of ice for prospective buyers. To make the ice last longer Hossain wraps the ice with a dirty plastic cover. From fishmongers to different community centres across the country--everyone who needs ice for mass consumption flocks to his shop.

"Most of the community centres in the city buy ice from me," claims Hossain.

People, however, fall ill easily after having such ice that is made in such dubious circumstances. Preetha, a twenty-year-old, went to a wedding at a community centre in Dhanmandi and fell ill after having chilled borhani. She was later diagnosed with typhoid. Many times people get sick after eating at a wedding and unfairly blame it on the biryani when it is more likely the ice in the borhani that is the culprit.

Every day hundreds of people go to these community centres that have swarmed the city landscape. Factories like Hossain's provide the largest share of these community centres' needs; and in the absence of any government's monitoring, these factories get a free rein over the buyers. Every day hundreds of people go to these community centres that have swarmed the city landscape. Factories like Hossain's provide the largest share of these community centres' needs; and in the absence of any government's monitoring, these factories get a free rein over the buyers.

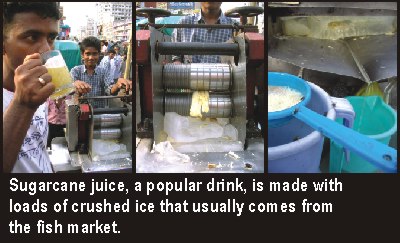

Another source of ice for these community centres is the fish sellers who resell the crushed ice they use to preserve fish in different bazaars in the city.

"When we are done, we resell this ice to different community centres or confectioneries who use it in borhani, lassi or faluda," Shamim, a fish seller at Karwan Bazaar Fish Market, says pointing his finger to cubes of ice that he has put in sacks-full of shrimp to keep them fresh.

The source of the ice Shamim uses to preserve his fish is even murkier. "It comes from Naraynganj," he explains, but is not sure if it is made from tap water or water from a contaminated Shitalakkha river that snakes through the district. "I really don't know," he admits. And he really doesn't care.

A couple of hundred yards along the main road towards "Chinese bus stand" from Mirpur 1 bus stand a narrow alley is laid out on the right. The 10 to 12 feet wide road has small shops of old iron scraps, nuts and bolts on its either side. A little further up is situated an unnamed (there is no signboard, neither any address) ice factory. A couple of hundred yards along the main road towards "Chinese bus stand" from Mirpur 1 bus stand a narrow alley is laid out on the right. The 10 to 12 feet wide road has small shops of old iron scraps, nuts and bolts on its either side. A little further up is situated an unnamed (there is no signboard, neither any address) ice factory.

The 50-plus manager cum helper cum technician of the ice factory Md Kibria is standing on the small yard, around three-foot by four -foot in area, adjoining the factory building. At his feet lies a rectangular block of ice right on the floor which is muddy like that of the floor of a fish market. The only customer, a 16 or 17-year-old vendor, who sells aakher rosh (sugarcane juice) in Mirpur 1, asks for one fourth of the block. Kibria readily drives his shovel through the middle of the block. When the joint is loosened Kibria, who has plastic shoes on with marks of liquid mud all over its body, kicks one piece aside. The same procedure follows and the half block is now ripped to divide it into another two parts. The customer brings out a dirty piece of rope, wraps it both ways and calls a rickshaw. As the rickshaw arrives he unceremoniously throws the piece on the place where the passengers place their feet and go away.

Inside the 20-foot by 30-foot ground floor ice factory one comes across the source of the roaring, deafening sound audible from half a kilometre. A giant machine, clearly long past its prime and discoloured from years of grime it has gathered for years, is on. On its left, rows of rectangular boxes are lined up. Water is poured into it and after treating it for 25 to 30 hours the boxes are filled with ice. Inside the 20-foot by 30-foot ground floor ice factory one comes across the source of the roaring, deafening sound audible from half a kilometre. A giant machine, clearly long past its prime and discoloured from years of grime it has gathered for years, is on. On its left, rows of rectangular boxes are lined up. Water is poured into it and after treating it for 25 to 30 hours the boxes are filled with ice.

"Where do you get the water?"

Kibria points to a few big pipes that have one end in the underground reserve tank and the other end into the boxes.

"But don't you boil the water before transforming it into ice?"

"Why, this water is provided by the WASA. The entire Dhaka is drinking this water," says a confident Kibria. When he is challenged that supply water is not free from impurities, he shakes his head knowledgeably, "when water is turned into ice no germs can stay alive".

Sattar Mian's makeshift fruit juice shop, raised on a four-wheeled van in front of the Karwan Bazar chicken market, is quite busy. It's May and the sun is particularly harsh for most of the day. And after a good sale or buy a glass of cold sharbat (juice) is very tempting. Fruits are arranged in shelves and a large round bowl is positioned in one corner. A sort of wooden bridge with a hole around the middle, goes over the big bowl. A sizeable piece of ice is placed over that bridge in a way that water emanating from the ice runs towards the hole and falls into the water. Both the water bowl and the piece of ice are out in the open and apart from the germs inside, they are also attracting a good amount of dust swirling all around.

But the seller and the customer are least bothered. "I am selling hundreds of glasses of sharbat every day and nobody has ever complained," Sattar has no doubt about the purity of his product. Farid Hossain, a vegetable vendor at Tejkunipara Bazar, is a little puzzled as he learns about the probability of germs in the sharbat he is enjoying so much. In the end he however takes side with Sattar, "Maybe there is poison in it, but I have had so many glasses of it without facing any problems. Perhaps, we poor people have a stronger stomach than the rich." But the seller and the customer are least bothered. "I am selling hundreds of glasses of sharbat every day and nobody has ever complained," Sattar has no doubt about the purity of his product. Farid Hossain, a vegetable vendor at Tejkunipara Bazar, is a little puzzled as he learns about the probability of germs in the sharbat he is enjoying so much. In the end he however takes side with Sattar, "Maybe there is poison in it, but I have had so many glasses of it without facing any problems. Perhaps, we poor people have a stronger stomach than the rich."

So just how dangerous is it to consume ice made with ordinary tap water, or worse water from a nearby pond or river? Well for one thing, the raw water from say, a lake or stream is heavily contaminated with bacteria from the waste of animals and humans. So unless it is boiled or disinfected with chemicals, it is unfit for drinking. Same goes for water from the direct WASA lines. In most middle class households, water from the tap is boiled for at least half an hour, cooled and then consumed. So ice made from raw water is very likely to contain germs that can lead to sever food poisoning.

Most people don't realise that ice can go bad. It is a myth that the freezing temperature of ice kills all bacteria and so consuming the ice will cause no harm. The truth is that bacteria is actually preserved in ice until conditions are favourable for growth. Which means when the bacteria in the ice find a nice warm stomach, it will wake up and wreak plenty of havoc. The cold temperature does slow germ reproduction, but once the ice melts and conditions for reproduction improve, germ populations may explode.

Just as in water a wide variety of bacteria can be found in ice, from Salmonella and E.coli to Hepatitis. Just as in water a wide variety of bacteria can be found in ice, from Salmonella and E.coli to Hepatitis.

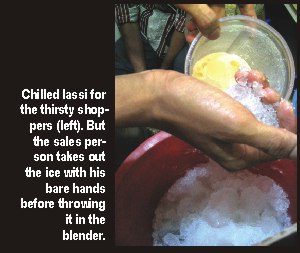

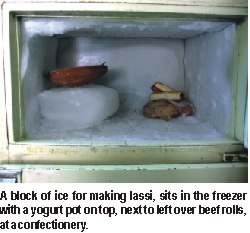

Improper handling and storing of ice also contaminate it. In most snack bars, confectioneries, or vending stalls, the ice is poured into the glass with utensils that are not washed properly or even bare hands. If the person handling the ice has not washed his hands properly after going to the bathroom or generally is not very particular about personal hygiene, germs will get into the ice and become unfit for consumption. The boxes in which ice is made, the buckets in which it is stored these too seldom go through proper cleaning and slime or mold can easily build up.

With the sweltering summer, ice is almost an essential food. It is used in street fruit juice stalls or small food joints selling juice from sugarcane, papaya, pineapple, melon etc, in chilled lassi. In community centres ice is used to make borhani (which most people prefer chilled). Restaurants, cafes, clubs and hotels also need a huge supply of ice to serve drinks to their customers. Apart from a few big hotels and restaurants that make their own ice (usually under hygienic conditions), most establishments buy ice from the market. This includes buying blocks of ice (some of which originally were used to keep fish fresh) as well as packaged ice. The packaging gives the illusion that the ice inside is clean but in most cases such ice is made under unhygienic conditions using tap water. With the sweltering summer, ice is almost an essential food. It is used in street fruit juice stalls or small food joints selling juice from sugarcane, papaya, pineapple, melon etc, in chilled lassi. In community centres ice is used to make borhani (which most people prefer chilled). Restaurants, cafes, clubs and hotels also need a huge supply of ice to serve drinks to their customers. Apart from a few big hotels and restaurants that make their own ice (usually under hygienic conditions), most establishments buy ice from the market. This includes buying blocks of ice (some of which originally were used to keep fish fresh) as well as packaged ice. The packaging gives the illusion that the ice inside is clean but in most cases such ice is made under unhygienic conditions using tap water.

So who are likely to get sick from ice contamination? Well, it could be anybody. Most people, while maybe a little sceptical about drinking water unless it is filtered, boiled or sterilized, are completely unconcerned about whether the ice they are consuming with the water or drink, is safe or not. When we go to a wedding we are very particular about drinking the water if it is bottled, but how many of us bother about the ice used in the borhani? Young people, especially school or university students, have a penchant for food on the street or just not from home and cold lassi or soft drinks with ice, are major favourites especially during summer. Young children and pregnant mothers are especially susceptible to germs in food including those found in ice or ice cream. Ice is universally popular; it is ubiquitous but unfortunately also usually unsafe. This puts the health of millions at risk.

But surprisingly a food item that can cause so much mischief, is not under any standard testing. Among the 142 food items that fall under BSTI ( Bangladesh Standard Testing Institute) ice is not one of them. This is because ice is not thought of as a food item and is considered a product that is used to cool food or keep them fresh. The fact that it is being consumed, and that too in large amounts everyday, seems to have escaped the minds of the concerned authorities. Which gives a free field to ice manufacturers who happily produce ice in the most unhealthy environments. Food sellers also cheerfully serve their customers without a thought that their clients may fall sick. And worst of all, the consumers, being completely unaware of the dangers of consuming contaminated ice, eagerly gulp down their chilled, summer beverage. But surprisingly a food item that can cause so much mischief, is not under any standard testing. Among the 142 food items that fall under BSTI ( Bangladesh Standard Testing Institute) ice is not one of them. This is because ice is not thought of as a food item and is considered a product that is used to cool food or keep them fresh. The fact that it is being consumed, and that too in large amounts everyday, seems to have escaped the minds of the concerned authorities. Which gives a free field to ice manufacturers who happily produce ice in the most unhealthy environments. Food sellers also cheerfully serve their customers without a thought that their clients may fall sick. And worst of all, the consumers, being completely unaware of the dangers of consuming contaminated ice, eagerly gulp down their chilled, summer beverage.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |